Introduction

Labor is defined by regular and painful uterine contractions that lead to cervical dilation and effacement. The primary goal of labor management is to achieve a vaginal delivery of a live neonate while minimizing maternal risk. The 3 components of labor that determine the success of a vaginal delivery include: passageway, passenger, and power.

The primary focus of this article is normal labor. A separate review article will discuss abnormalities within labor and delivery.

Passageway

This component refers to the maternal bony pelvis and the soft structures of the birth canal, including the cervix, vagina, and vaginal introitus.

The maternal pelvis is divided into imaginary planes that hold obstetric significance: the plane of the pelvic inlet, the plane of the midpelvis, and the plane of the pelvic outlet.

- The pelvic inlet separates the false pelvis (part of abdominal cavity between the iliac crests) from the true pelvis (below the brim of the pelvis). The smallest diameter within the pelvic inlet is the obstetrical conjugate—the distance from the sacral promontory to the posterior pubic symphysis. This diameter cannot be directly measured clinically; rather, it is extrapolated from the diagonal conjugate (measured on bimanual examination), which is the distance from the sacral promontory to the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis. The pelvic inlet is clinically important because the fetal head is considered engaged (ie, beginning descent of labor) once it passes through this plane into the true pelvis.

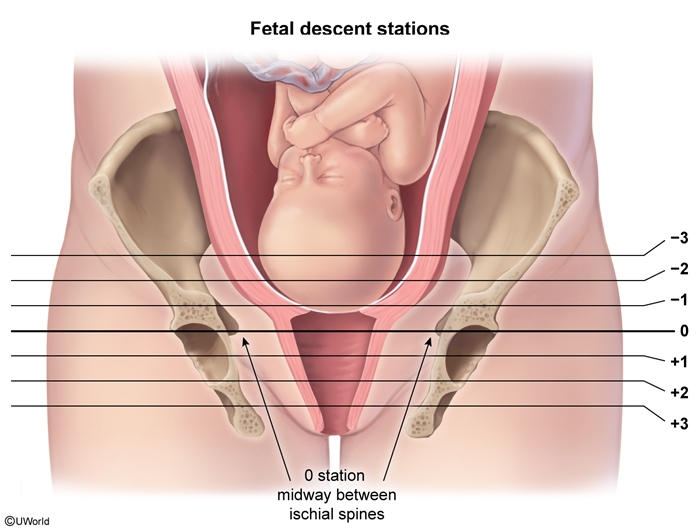

- The midpelvis, measured at the level of the ischial spines, is the smallest diameter (about 10 cm) of the maternal pelvis that a fetus must pass through during labor. The midpelvis is clinically important because fetal station (level of fetal descent) is measured in relation to the pelvic ischial spines (

figure 1

figure 1 - Pelvic outlet is bounded by the pubic arch, the ischial tuberosities, and the coccyx. In the absence of significant bony disease (eg, contractures, pelvic fractures) this is rarely a cause of labor obstruction.

There are 4 main pelvic shapes described based on the greatest transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet: gynecoid, anthropoid, android (ie, "male" pelvis), and platypelloid. Most women have a gynecoid pelvic shape, which most readily facilitates a vaginal delivery. Android and platypelloid pelvic shapes are more likely to present with labor obstruction with transverse fetal positioning (ie, neither occiput anterior nor posterior).

Although it is helpful to evaluate the maternal pelvis in all patients to track and manage labor progress, pelvimetry (quantitative measurements) has been replaced with trial of labor in all patients because measurements of both fetal size and maternal pelvis are typically inaccurate and do not correlate with clinical outcomes (ie, they are not reliable at predicting the success of vaginal deliveries). In addition, passageway (specifically the bony pelvis) is a fixed labor variable that cannot be altered or modified.

Passenger

This component refers to the fetus and its various positioning factors. Assessment of the passenger requires evaluation of fetal lie, presentation, position, and size.

- Fetal lie: refers to the orientation of the fetal spine in relation to the longitudinal axis of the uterus; fetal lie can be vertical, transverse, or horizontal

- Fetal presentation: refers to the fetal part closest to the birth canal; most often this is either vertex (fetal head) or breech (fetal buttocks) but can occasionally include compound presentations like fetal shoulder or arm

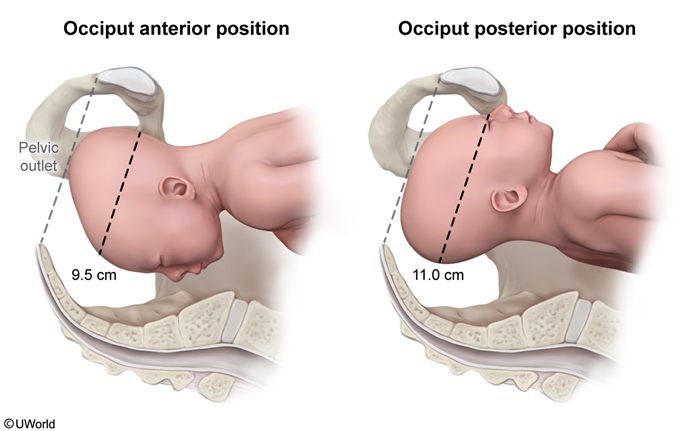

- Fetal position ( : fetal orientation in relation to the maternal pelvis (ie, occiput located anterior vs posterior)

figure 2

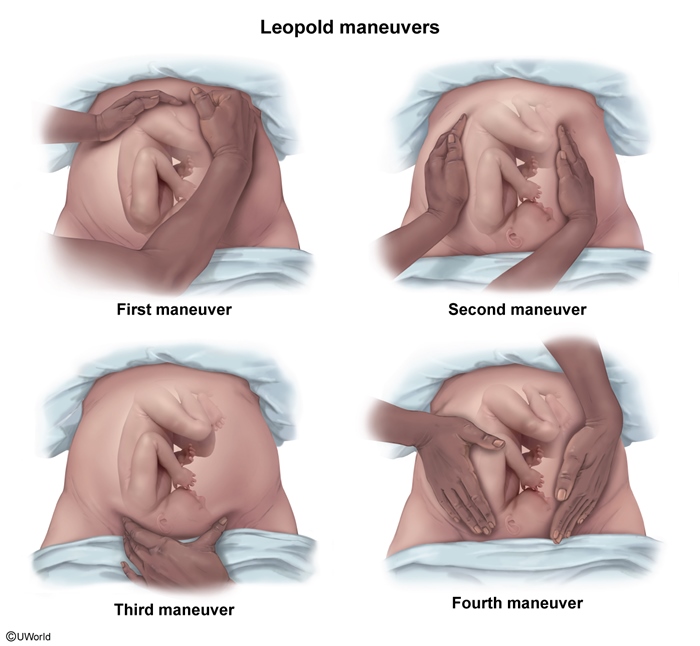

figure 2 - Fetal size: often roughly estimated through Leopold maneuvers ( , which involves palpating the maternal abdomen to estimate fetal size; particularly for determining macrosomia (eg, estimated fetal weight >4,500 g) risk

figure 3

figure 3

This component of labor is slightly modifiable (eg, maternal repositioning for fetal rotation or manual rotation of fetal head to occiput anterior) but is largely a fixed (size of passenger) variable.

Power

The final component involves the strength and frequency of uterine contractions. Uterine contractions generate downward force that gradually dilates and effaces (thins) the cervix, propels fetal descent, and ultimately results in delivery of the neonate.

Importantly, this is the most modifiable component of labor and can be actively manipulated (via labor augmentation) to facilitate a vaginal delivery.

Management of labor

Upon admission for labor, maternal and fetal assessments are performed, which include:

Maternal assessment

- Review of prenatal record and complications during pregnancy

- Vital signs

- Laboratory evaluation (eg, complete blood count, blood type, infectious disease labs [HIV, syphilis])

- Frequency and duration of contractions through tocodynamometry

- Physical examination, with a particular focus on maternal pelvis and the digital cervical examinations

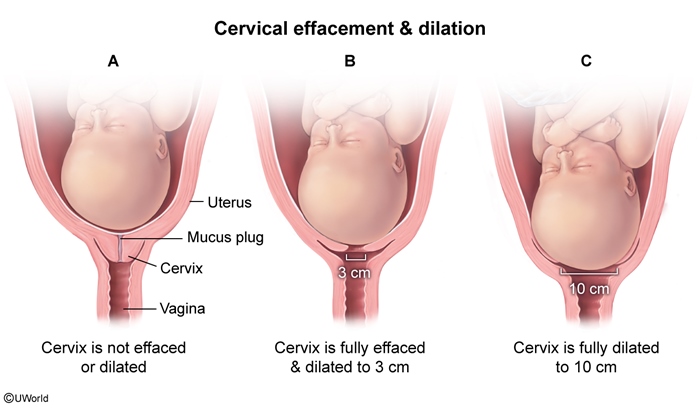

The cervical examination is the primary means of monitoring labor progress

- Fetal presentation: fetal vertex must be confirmed

- Dilation: opening of the cervix measured in centimeters at the level of the internal os

- Effacement: percentage of thinning and shortening of the cervix

- Station: position of fetal head in the pelvis in relation to the ischial spines

- Fetal position: orientation of fetal vertex in pelvis (eg, occiput anterior); more easily identified at greater dilations and lower stations

Cervical examinations are performed at admission (baseline examination), routinely every 4 hours during the first stage of labor, with abrupt fetal heart rate changes, and with maternal impulse to push (to ensure complete cervical dilation has occurred). Importantly, additional cervical examinations are limited to prevent iatrogenic intrauterine infections (to avoid incidental spread of vagina flora into the uterine cavity).

Fetal assessment

- Fetal heart rate monitoring (

- Fetal size (a rough estimate made via Leopold maneuvers), lie, orientation, and position

Stages of Labor

Labor consists of 3 distinct stages:

- First stage: time from onset of labor to complete cervical dilation (10 cm)

- Second stage: time from complete cervical dilation to fetal delivery

- Third stage: time between fetal delivery and placental expulsion

First stage of labor

The first stage of labor begins with the onset of regular, painful contractions and ends at complete (10 cm) cervical dilation. The first stage of labor is divided into 2 phases:

- Latent phase (0-6 cm dilation):

- Cervical change: In general, the cervix slowly dilates from 0 cm to 6 cm with progressive cervical effacement.

- There is no defined or expected rate of cervical change during the latent phase.

- Active phase (6-10 cm dilation):

- Cervical change: The rate of cervical dilation varies but often progresses more rapidly than during the latent phase.

- On average, the rate of cervical dilation is 1-2 cm/hr. But, the minimum rate considered normal cervical dilation is ≥1 cm every 2 hours.

During the first stage of labor, progress is monitored through serial cervical examinations and external monitors (Doppler for fetal heart rate and external tocodynamometry for contractions). Because the most modifiable variable in labor is the power component, significant focus is placed on contractions.

Most commonly, contraction surveillance requires only an external tocodynamometer, which reveals the frequency and the duration of each contraction; it does not measure pressure or strength. Therefore, contraction strength is inferred indirectly through serial cervical examinations and appropriate progression in labor (advancing cervical dilation).

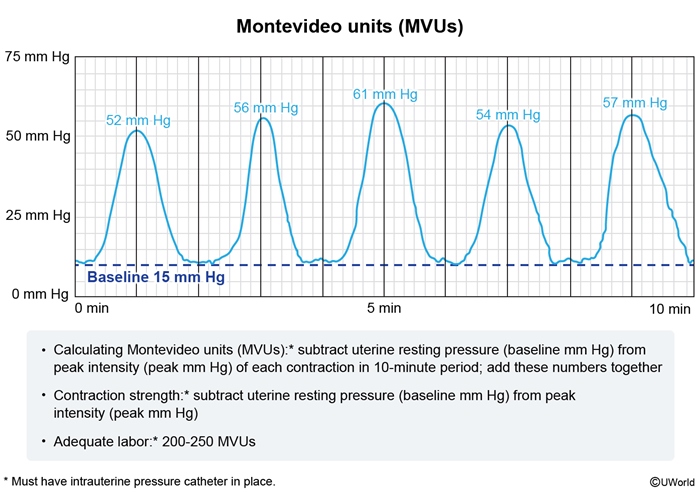

However, labor with a protracted course (slower rates of cervical change) requires additional quantitative information about contraction intensity and adequacy. Adequate contractions are those that lead to a normal and expected rate of cervical change and fetal descent. Adequacy can be determined by calculating Montevideo units (MVUs

Because the external monitor does not measure pressure, MVU calculation requires an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC), which is a pressure-sensing catheter that lies within the amniotic cavity. Placement requirements include:

- rupture of amniotic membranes

- sufficient cervical dilation to allow for placement

- no contraindication to labor or vaginal delivery (eg, placenta previa, vasa previa)

If MVUs are inadequate (<200 MVUs), labor can be augmented with oxytocin, which increases both the strength and frequency of contractions.

Second stage of labor

The second stage of labor begins when the cervix is completely dilated (10 cm) and ends with delivery of the newborn. This stage requires sustained maternal expulsive efforts in coordination with uterine contractions of adequate frequency and strength. Progress is measured by fetal descent (fetal station).

Major factors that affect the length of the second stage include parity and the use of epidural analgesia. There are no definitive time parameters for the second stage of labor; however, the longer the second stage of labor, the more likely the development of maternal (eg, postpartum hemorrhage, 3rd- or 4th-degree lacerations) and fetal (eg, low Apgar score, neonatal intensive care unit admission) morbidity. Therefore, the following rough guidelines are used:

- Nulliparous patients (those who have not previously given birth): up to 3 hours, but varies widely

- Multiparous patients: 30 minutes to 2 hours

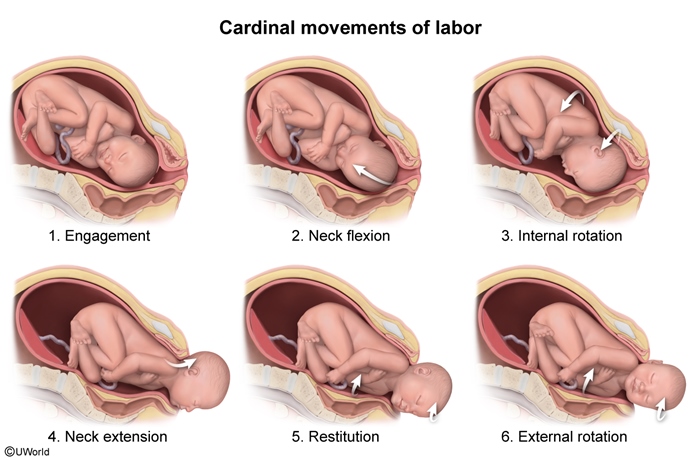

The first and second stages of labor require the fetus to make the cardinal movements of labor to navigate through the bony maternal pelvis, which involves

- Engagement, descent, and flexion: The widest diameter of the fetal head aligns with the widest diameter of the pelvic inlet and descends transverse (ie, facing either right or left) in line with the widest axis of the pelvic inlet (now considered engaged). Further passage through the pelvis constitutes descent, during which resistance against the bony pelvis and pelvic musculature causes the fetal neck to flex (chin toward the chest). This creates a smaller fetal head diameter for easier passage through the pelvis.

- Internal rotation: The upper pelvis is widest along the transverse axis, but the lower pelvis is widest along the anterior-posterior axis. Therefore, the fetal head internally rotates 90 degrees to an anterior-posterior position (eg, occiput anterior), enabling the fetal head to better fit through the lower pelvis and aligning the head with the forward curve of the pelvis.

- Extension: Once the fetal occiput reaches the pubic symphysis, neck extension enables the head to pass completely under the pubic symphysis and continue moving forward and upward; extension leads to crowning at the vaginal opening.

- Restitution: The fetal head is delivered in an anterior-posterior position (eg, occiput anterior) but quickly undergoes a slight rotation to return to its anatomic position in relation to the shoulders. This movement, known as restitution, facilitates passage of the shoulders through the pelvis.

- External rotation: Following restitution, the shoulders rotate to fit through the anterior-posterior axis of the pelvic outlet, which causes another slight rotation of the fetal head, bringing the head back to its original transverse position.

- Expulsion of the shoulders and body: The anterior shoulder passes under the pubic symphysis and emerges. Once the posterior shoulder emerges, expulsion of the body quickly follows.

Third stage of labor

The third stage of labor begins after delivery of the newborn and ends with expulsion of the placenta. Placental expulsion typically occurs within 5 minutes, but a time limit of 30 minutes is set for the third stage of labor due to increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage at >30 minutes.

During the third stage of labor, contractions are irregular and of low intensity, which limits how quickly the placenta can separate from the uterus. Therefore, active management of the third stage of labor is recommended with uterine massage and gentle downward traction on the umbilical cord to facilitate placental separation and expulsion.

The clinical signs of placental separation include:

- Umbilical cord lengthening

- Increased vaginal bleeding

- Change of uterine shape, from elongated to spherical

Once the placenta is completely separated from the uterus, expulsion is typically rapid.