Acid-base disorders are characterized by changes in the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+) in the body. Increased H+ concentration (acidosis) can lead to an abnormally low blood pH (acidemia) and decreased H+ concentration (alkalosis) can lead to an abnormally high blood pH (alkalemia); however, if compensation occurs, acidosis and/or alkalosis may be present without acidemia or alkalemia. Acidosis and alkalosis may be respiratory or metabolic in origin depending on the cause of the imbalance; they can also coexist as mixed acid-base disorders. Diagnosis is made based on arterial blood gas (ABG) results. In metabolic acidosis, calculation of the anion gap can also help determine the cause and reach a precise diagnosis. In metabolic alkalosis, urine chloride (Cl‑) concentration can help identify the cause. Treatment is based on the underlying cause.

-

Acid-base processes [1]

- Acidosis: the processes by which H+ concentration is increased

- Alkalosis: the processes by which H+ concentration is decreased

-

pH scale

- A logarithmic scale that expresses the acidity or alkalinity of a solution based on the concentration of H+ (pH = -log[H+])

- Neutral pH is 7; lower values are acidic and higher values are alkaline.

-

Blood pH abnormalities

- Acidemia; : abnormally low blood pH (pH < 7.35)

- Alkalemia; : abnormally high blood pH (pH > 7.45)

-

The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation allows for the calculation of pH from HCO3- and PCO2: pH = 6.1 + log([HCO3-]/[0.03 × pCO2])

- 6.1 = pKa of carbonic acid

- 0.03 = solubility constant of PCO2

| Pathophysiology of acid-base disorders [2] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory acidosis | Respiratory alkalosis | Metabolic acidosis | Metabolic alkalosis | ||

| pH |

|

|

|

|

|

| PCO2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| HCO3- |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mechanism |

|

|

|

|

|

| Compensation mechanisms in acid-base disorders |

|

|

|

|

|

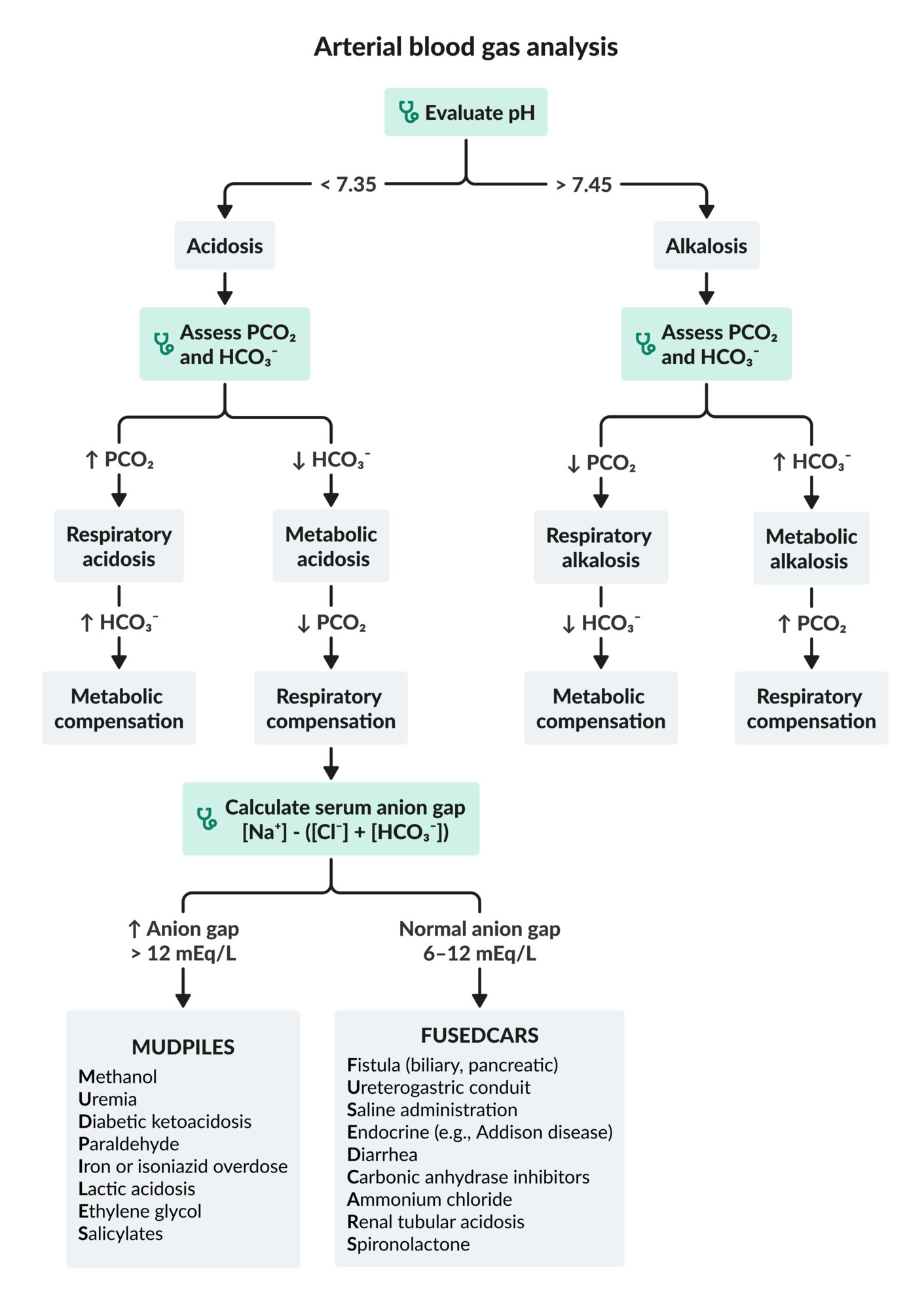

Approach to acid-base disorders [1][3]

- Perform an initial clinical evaluation: to help identify the most likely underlying cause

- Order initial laboratory studies: ABG, BMP [4][5]

- Determine the primary acid-base disorder: i.e., using pH, PCO2, and HCO3-

-

Calculate the expected compensatory (or secondary) response.

- Mixed acid-base disorder: The expected compensatory response differs from the laboratory findings.

- No mixed acid-base disorder: The expected compensatory response aligns with the laboratory findings.

-

Perform further diagnostic workup (to determine the mechanism and the cause), e.g.:

- In metabolic acidosis: anion gap and delta gap

- In metabolic alkalosis: urinary chloride and potassium levels

Careful clinical evaluation is an important first step in the assessment of acid-base disorders, as it can provide important diagnostic clues that can help determine the underlying cause.

Initial blood gas analysis

There are different methods for the assessment of acid-base status; the following method is just one example.

Suggested approach

- Evaluate blood pH (reference range: 7.35–7.45).

- Evaluate HCO3- (reference range: 22–28 mEq/L).

- Evaluate PCO2 (reference range: 33–45 mm Hg).

Interpretation

-

pH < 7.35 (acidemia): Primary disorder is an acidosis.

- ↓ pH and ↓ HCO3-: metabolic acidosis

- ↓ pH and ↑ PCO2: respiratory acidosis

-

pH > 7.45 (alkalemia): Primary disorder is an alkalosis.

- ↑ pH and ↑ HCO3-: metabolic alkalosis

- ↑ pH and ↓ PCO2: respiratory alkalosis

Further considerations

-

Evaluate PO2.

- High: hyperoxemia

- Low: hypoxemia

- See also “Respiratory failure.”

SMORE: change in PCO2 in the Same direction as pH →Metabolic disorder; change in PCO2 in the Opposite direction to pH →REspiratory disorder

Corrections to central venous blood gas values [6][7]

Reference values for venous blood gas (VBG) are different from those for ABG; central VBG results can be corrected to approximate ABG.

- Arterial pH = venous pH + 0.03–0.05 units

- Arterial PCO2 = venous PCO2 – 5 mm Hg

Compensation (acid-base) [1][8]

- Definition: physiological changes that occur in acid-base disorders in an attempt to maintain normal body pH

-

Compensatory changes

- In metabolic disorders: rapid compensation within minutes through changes in minute ventilation (respiratory compensation)

- In respiratory disorders: typically slow compensation over several hours to days through changes in urine pH (metabolic compensation)

- See also “Compensation mechanisms in acid-base disorders.”

-

Assessment and interpretation: Calculate the expected compensation; see “Calculation of compensatory response.”

- Primary respiratory disorders

- Measured HCO3- > expected HCO3-: metabolic alkalosis in addition to respiratory disturbance

- Measured HCO3- < expected HCO3-: metabolic acidosis in addition to respiratory disturbance

- Primary metabolic disorders

- Measured PCO2 > expected PCO2: respiratory acidosis in addition to metabolic disturbance

- Measured PCO2 < expected PCO2: respiratory alkalosis addition to metabolic disturbance

- Primary respiratory disorders

| Calculation of compensatory response | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary acid-base disturbance | Expected compensation [1][9] | ||

| Metabolic acidosis |

|

||

| Metabolic alkalosis |

|

||

| Respiratory acidosis | Acute |

|

|

| Chronic |

|

||

| Respiratory alkalosis | Acute |

|

|

| Chronic |

|

||

Discordance between the measured compensatory response and the expected compensatory response suggests a secondary acid-base disturbance.

In primary metabolic disorders, respiratory compensation develops quickly (within hours), whereas metabolic compensation may take 2–5 days to develop in primary respiratory disorders.

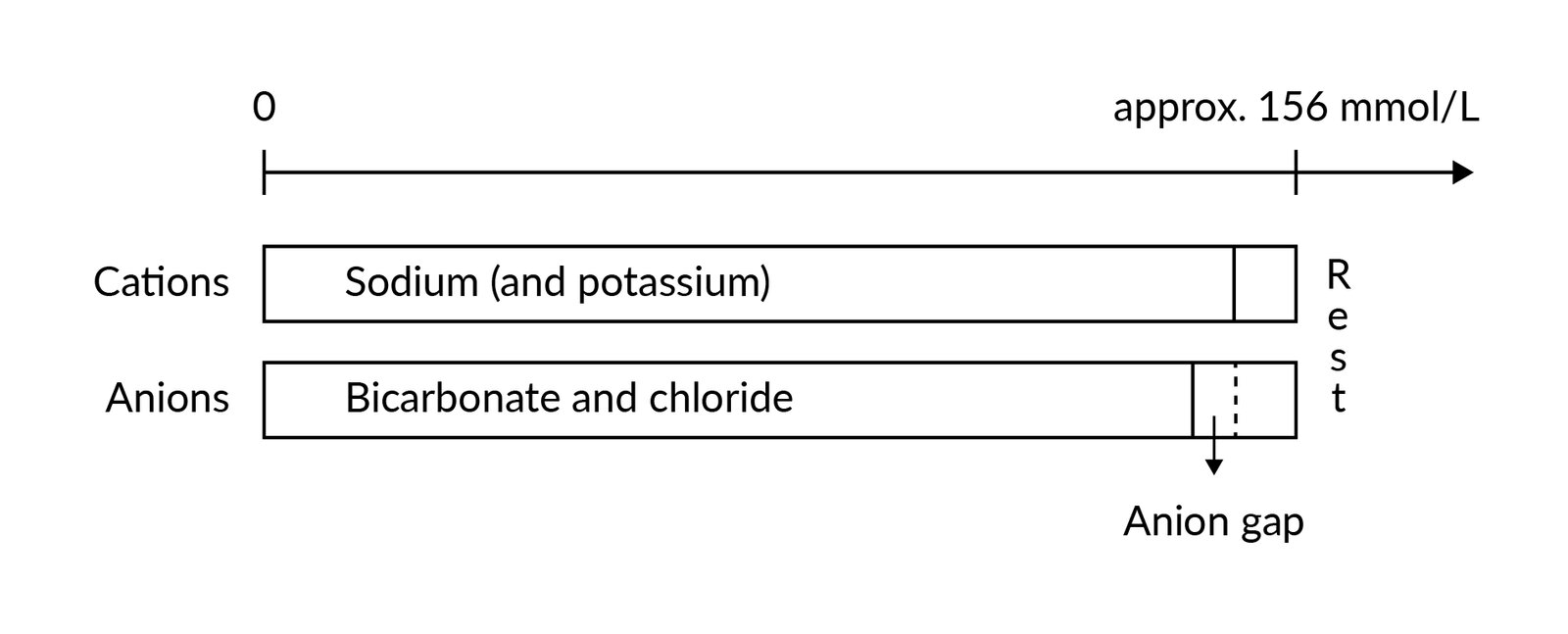

General principles

-

Calculation of the anion gap is the first step in the evaluation of metabolic acidosis.

- Maintenance of electrical neutrality requires that the total concentration of cations approximate that of anions.

- Anion gap: the difference between the concentration of measured cations and measured anions

- High anion gap: increased concentration of organic acids such as lactate, ketones (e.g., beta-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate), oxalic acid, formic acid, or glycolic acid, with no compensatory increase in Cl-.

- Normal anion gap: primary loss of HCO3- compensated with ↑ Cl-

- The measured serum sodium (Na+), not the corrected serum Na+, should be used in the formulas, even if glucose levels are high.

- Depending on the results, further evaluation and calculations may be needed (see specific subsections below).

| Metabolic acidosis formulas [1][10][11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anion gap | Serum anion gap |

|

| Urine anion gap |

|

|

| Osmolal gap | Serum osmolal gap |

|

| Urine osmolal gap |

|

|

| Delta gap |

|

|

| ||

High anion gap metabolic acidosis [1][11]

Review clinical features and initial studies and follow a stepwise approach to identify the underlying cause of high anion gap metabolic acidosis.

-

Exclude accumulation of endogenous organic acids.

- Exclude ketoacidosis: Consider measuring ketone levels in urine or serum (e.g., beta-hydroxybutyrate).

- Exclude lactic acidosis: Measure or review lactate levels.

- Exclude uremia: Measure or review BUN and creatinine levels.

-

Consider accumulation of exogenous organic acids (ingestion) as the cause: e.g., if the cause remains unclear, or initially if the patient is comatose

- Consider obtaining serum or urine toxicology screen.

- Calculate serum osmolal gap: If elevated (≥ 10 mOsm/kg), consider propylene glycol, ethylene glycol, diethylene glycol, methanol, and isopropanol as potential causes.

- Calculate the delta gap: to exclude concomitant acid-base disturbances

| Etiology of high anion gap metabolic acidosis | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Accumulation of endogenous organic acids |

|

| Accumulation of exogenous organic acids |

|

Causes of high anion gap acidosis (MUDPILES): Methanol toxicity, Uremia, Diabetic ketoacidosis, Paraldehyde, Isoniazid or Iron overdose, Inborn error of metabolism, Lactic acidosis, Ethylene glycol toxicity, Salicylate toxicity

Concomitant acid-base disturbances [10][11]

Calculation of the delta gap can help determine if another acid-base disturbance is present in addition to a high anion gap metabolic acidosis. Cut-off values may vary depending on the source.

- Delta gap < 1 : Hyperchloremic or normal anion gap metabolic acidosis is present in addition to high anion gap metabolic acidosis. [10]

- Delta gap 1–2 : Only high anion gap metabolic acidosis is present.

- Delta gap > 2 : A metabolic alkalosis is present in addition to high anion gap metabolic acidosis. [11]

Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis

Review clinical features and initial studies and consider further diagnostic workup to determine the underlying cause of normal anion gap metabolic acidosis.

-

Calculate the urine anion gap

- Negative urine anion gap: Acidosis is likely due to loss of bicarbonate.

- Positive urine anion gap: Acidosis is likely due to decreased renal acid excretion.

-

Consider calculating the urine osmolal gap

- Preferred over urine anion gap if the urine pH is > 6.5 or urine Na+ is < 20 mEq/L

- ↓ Urine osmolal gap (< 80–100 mOsm/kg) suggests impairment in the excretion of urinary ammonium. [13][14]

| Etiology of normal anion gap metabolic acidosis | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Loss of bicarbonate (negative urine anion gap) |

|

| Decreased renal acid excretion (positive urine anion gap) |

|

Causes of normal anion gap acidosis (FUSEDCARS): Fistula (biliary, pancreatic), Ureterogastric conduit, Saline administration, Endocrine (Addison disease, hyperparathyroidism), Diarrhea, Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, Ammonium chloride, Renal tubular acidosis, Spironolactone

A neGUTive urine anion gap may be due to GI loss of bicarbonate.

Abnormal anion gap without metabolic acidosis [15]

-

Etiology of low anion gap

- Hypoalbuminemia → ↓ unmeasured anions → ↓ anion gap

- Paraproteinemia (e.g., in multiple myeloma), severe hypercalcemia, severe hypermagnesemia, and/or lithium toxicity → ↑ unmeasured cations → ↓ anion gap

-

Etiology of high anion gap

- Severe hyperphosphatemia → ↑ unmeasured anions → ↑ anion gap [16]

- Severe hypocalcemia and/or hypomagnesemia → ↓ unmeasured cations → ↑ anion gap

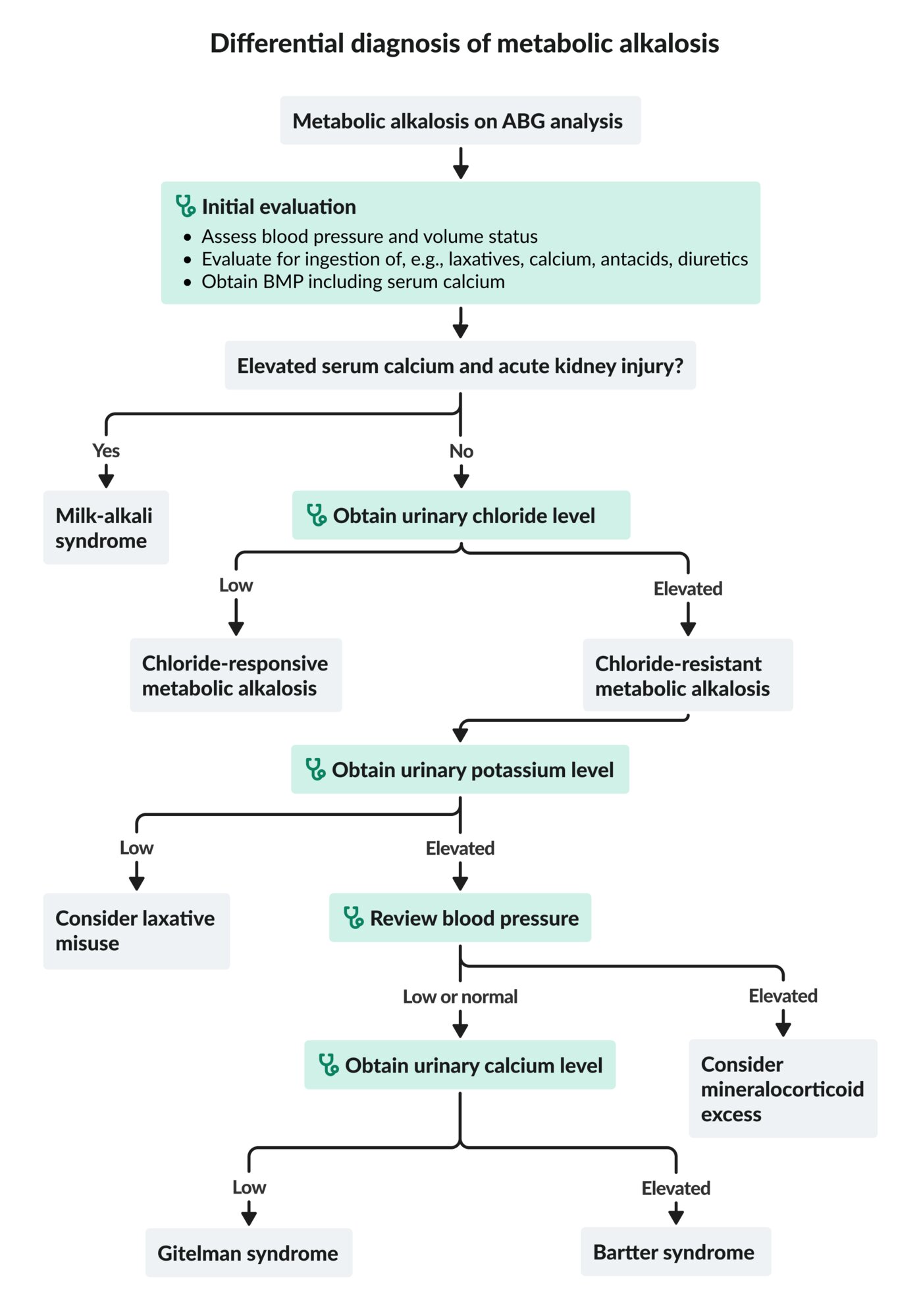

Approach [1]

- Assess the patient's blood pressure and volume status.

- Evaluate for exogenous ingestion (e.g., laxatives, calcium, alkali load, diuretics).

-

Obtain BMP and serum calcium, urinary chloride, and urinary potassium levels.

- Low urine chloride(< 25 mEq/L): chloride-responsive metabolic alkalosis

-

High urine chloride(> 40 mEq/L): chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis; check urine potassium.

- High urine potassium (> 30 mEq/L): Review blood pressure.

- Elevated blood pressure: Consider mineralocorticoid excess as a potential cause.

- Low or normal blood pressure: Consider Gitelman syndrome or Bartter syndrome as a potential cause.

- Low urine potassium (< 20 mEq/L): Consider laxative abuse as a potential cause.

- High urine potassium (> 30 mEq/L): Review blood pressure.

Elevated calcium with renal failure suggests milk-alkali syndrome.

Etiology

| Etiology of metabolic alkalosis [1][17] | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Chloride-responsive metabolic alkalosis (urine chloride < 25 mEq/L) |

|

| Chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis (urine chloride > 40 mEq/L) |

|

Respiratory acidosis

- Seen in alveolar hypoventilation; see also “Respiratory insufficiency.”

- Establish the expected chronicity based on clinical presentation using the following rule:

- HCO3- increases by 1 mEq/L for every 10 mm Hg increase in PCO2 above 40 mm Hg: suggests acute respiratory acidosis

- HCO3- increases by 4–5 mEq/L for every 10 mm Hg increase in PCO2 above 40 mm Hg: suggests chronic respiratory acidosis

- Expected and measured HCO3- values may differ if additional metabolic disturbances are present; see “Compensation (acid-base).”

| Etiology of respiratory acidosis [1] | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Acute respiratory acidosis |

|

| Chronic respiratory acidosis |

|

Respiratory alkalosis

- Seen in hyperventilation; see also “Respiratory insufficiency.”

- Establish the expected chronicity based on clinical presentation using the following rule:

- HCO3- decreases by 2 mEq/L for every 10 mm Hg decrease in PCO2 below 40 mm Hg: suggests acute respiratory alkalosis

- HCO3- decreases by 4–5 mEq/L for every 10 mm Hg decrease in PCO2 below 40 mm Hg: suggests chronic respiratory alkalosis

- Expected and measured values may differ if additional metabolic disturbances are present; see “Compensation (acid-base).”

| Etiology of respiratory alkalosis [19] | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Acute respiratory alkalosis |

|

| Chronic respiratory alkalosis |

|

| Acid-base disturbances associated with GI disorders [20][21] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI disturbance | Acid-base disturbance | Cl- | K+ | Na+ |

| Severe diarrhea or laxative use | Metabolic acidosis | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Prolonged vomiting or nasogastric suctioning | Metabolic alkalosis | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

The loss of bicarbonate-rich fluid in severe diarrhea may cause non-anion gap metabolic acidosis.

General considerations [2]

- Treatment of acid-base disorders should target the underlying cause.

- Medications (e.g., sodium bicarbonate, acetazolamide) used to correct acid-base abnormalities should be initiated in consultation with a specialist (e.g., nephrologist).

- Mechanical ventilation may be indicated in severe respiratory disorders and severe metabolic acidosis.

- Optimize ventilation in mechanically ventilated patients as needed.

- Electrolyte imbalances should be corrected: See “Disorders of potassium balance” and “Electrolyte repletion.”

Respiratory acidosis

- Severe acute respiratory acidosis: Consider noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation.

- See also “COPD,” “Opioid intoxication,” and “Benzodiazepine overdose.”

Respiratory alkalosis

- Acute respiratory alkalosis accompanied by increased work of breathing: Consider mechanical ventilation.

- See also “Treatment of congestive heart failure,” “Treatment of pulmonary embolism,” and “Salicylate toxicity.”

Metabolic acidosis

-

Acute severe metabolic acidosis

- Consider intravenous sodium bicarbonate and mechanical ventilation (see “High-risk indications for mechanical ventilation”)

- See also “Diabetic ketoacidosis” and “Salicylate toxicity.” [4][22]

-

Chronic metabolic acidosis

- Consider oral sodium bicarbonate

- See also “Chronic kidney disease,” and “Diarrhea.”

Metabolic alkalosis

-

Chloride-responsive metabolic alkalosis

- Start isotonic saline to increase urinary bicarbonate excretion and correct extracellular volume loss

- See “Intravenous fluid therapy” and “Treatment” in “Dehydration and hypovolemia.”

-

Chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis

- Consider bicarbonate excess as a potential cause and administer acetazolamide.

- See also “Cushing Syndrome” and “Primary hyperaldosteronism.”