Diagnostic approach

- ABCDE approach

- Targeted clinical evaluation

- Compartment pressure measurement

- Labs for rhabdomyolysis (e.g., CPK, CMP)

- X-rays and/or ultrasound of affected area

Red flag features

- Pain out of proportion to injury

- Pain worsens with passive stretching

- Tight, wood-like muscles

- Paresthesia

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Intracompartmental pressure ≥ 30 mm Hg

- Delta pressure ≤ 30 mm Hg

Management checklist

- Consult surgery immediately.

- Emergency fasciotomy if acute compartment syndrome is likely or confirmed

- Remove constrictive dressings, splints, and devices.

- Place affected limb at heart level.

- Acute pain management with oral and/or parenteral analgesics

- Reduce displaced fractures.

- IV fluid resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock

- Supplemental oxygen

- Serial clinical exams

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) is caused by tissue ischemia due to increased pressure within a fascial compartment. It is a surgical emergency that is characterized by rapidly progressive pain and swelling in an extremity and is often precipitated by traumatic injury. Signs of poor tissue perfusion (e.g., pallor, pulselessness) and nerve damage (e.g., paresthesia, paralysis) occur in later stages of ACS and are suggestive of irreversible tissue damage. Diagnosis of ACS is based on clinical findings and confirmed by measurement of intracompartmental pressures. ACS requires fasciotomy within 4–6 hours to prevent irreversible tissue necrosis.

Other types of compartment syndrome include chronic exertional compartment syndrome, which is characterized by recurrent extremity pain during exercise or exertion, and abdominal compartment syndrome, which is caused by increased pressure within the abdominal cavity. See “Chronic compartment syndrome” and “Abdominal compartment syndrome” for details.

| Etiology and risk factors for acute compartment syndrome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Causes of external compression | Causes of internal compression | |

| Trauma-related causes |

|

|

| Non-trauma-related causes |

|

|

Because shock leads to reduced peripheral circulation, patients with polytrauma are at a high risk of compartment syndrome with muscle ischemia.

External or internal forces as initiating event → increased compartment pressure→ obstruction of venous outflow and collapse of arterioles→ decreased tissue perfusion → lower oxygen supply to muscles → irreversible tissue damage (necrosis) to muscles and nerves after 4–6 hours of ischemia

Signs and symptoms of ACS typically progress rapidly over a few hours but the presentation and onset are highly variable. [1][2][3]

-

Early features

-

Pain out of proportion to the extent of apparent injury

- Worsens with passive stretching or extension of muscles

- Extreme tenderness to touch

- Soft tissue swelling

- Tight, wood-like muscles

-

Pain out of proportion to the extent of apparent injury

-

Later features

- Neurologic deficits

- Paresthesia (e.g., pins and needles sensation)

- Sensory deficits

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Impaired perfusion

- Cold extremity with pallor or cyanosis (uncommon)

- Absent or weak distal pulses

- Neurologic deficits

Clinical features of compartment syndrome may be difficult to detect, especially in patients who are unable to report sensory symptoms (e.g., patients with altered mental status, comorbid trauma, or regional anesthesia). [3]

Arterial pulses remain detectable in all but the most severe cases of ACS and should not be used to exclude the diagnosis. [4]

The 6 Ps of acute limb ischemia (Pain, Pallor, Paresthesias, Poikilothermia, Pulselessness, and Paralysis) are seldom all present in early ACS.

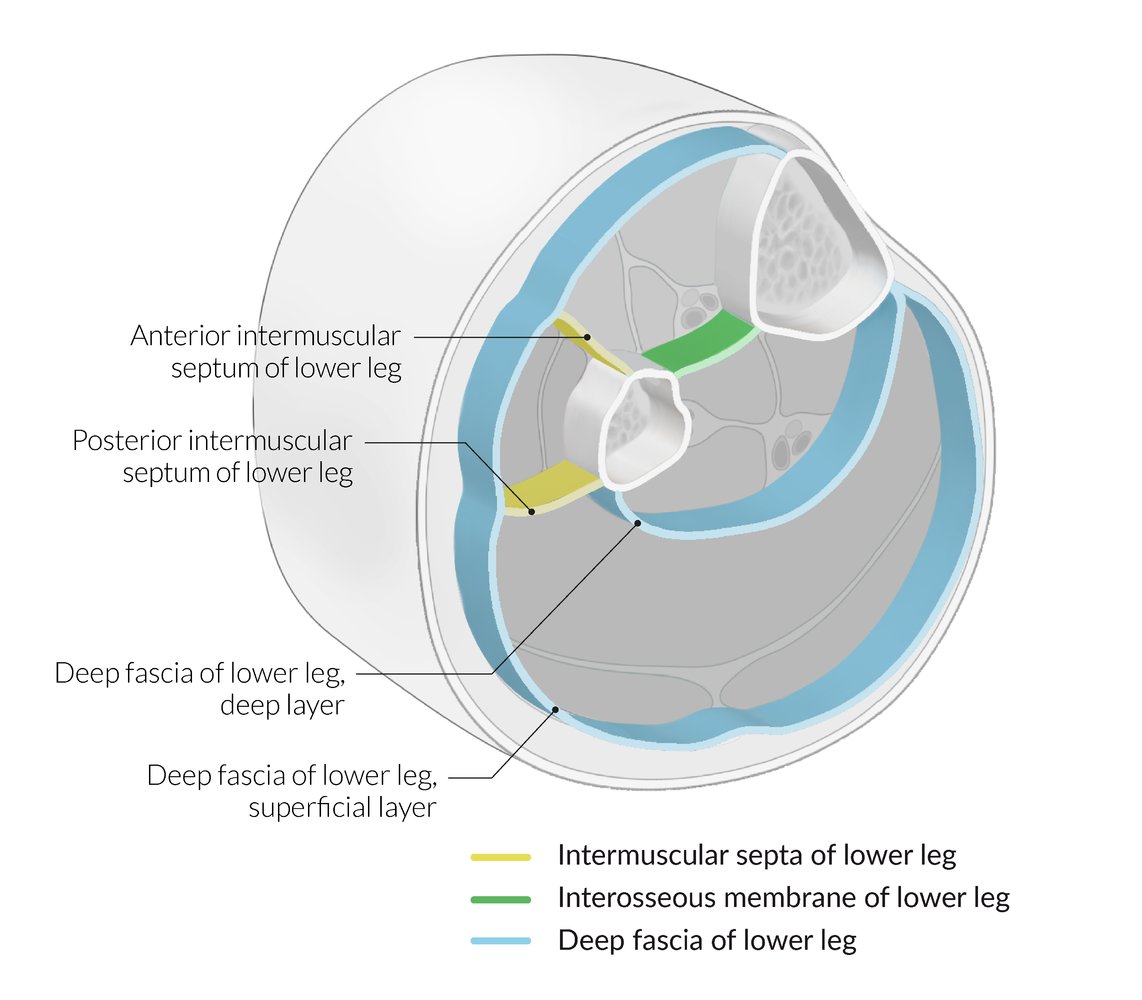

Acute compartment syndrome may occur in any enclosed fascial compartment. It most commonly occurs in the lower legs and arms but the feet, hand, thighs, and gluteal region may also be affected. For acute abdominal hypertension and compartment syndrome, see “Abdominal compartment syndrome.”

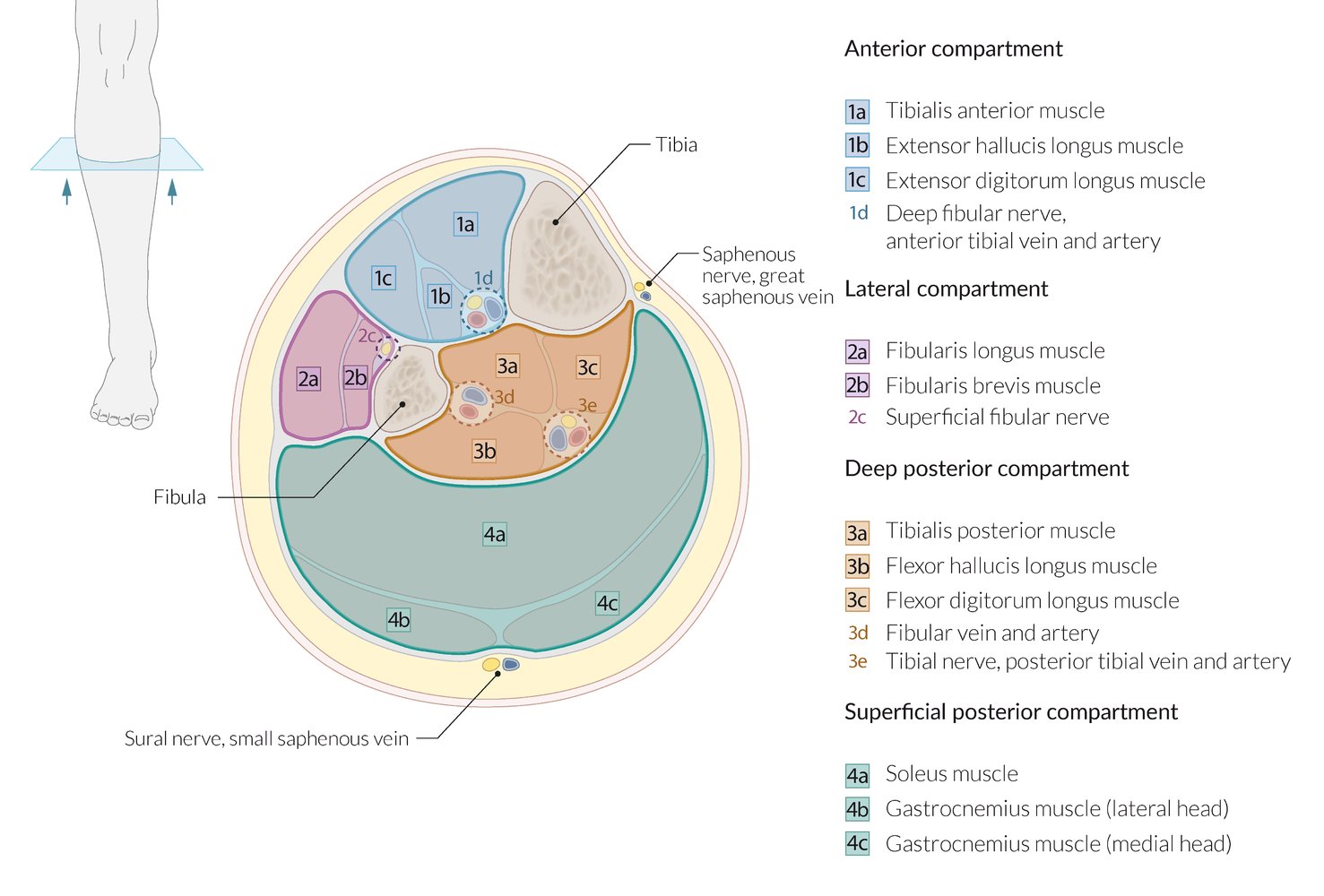

Anterior compartment syndrome of the lower leg

- Prevalence: most common type of ACS

-

Etiology

- Usually due to trauma to the anterior compartment of the leg (e.g., tibial fracture)

- See also “Etiology of acute compartment syndrome."

-

Clinical features

- Often involves injury to the deep peroneal (fibular) nerve

- Pain: with passive flexion of the toe

- Motor: limited ankle dorsiflexion, inversion, eversion and toe extension

- Sensory: loss of sensation/paresthesia in the deep peroneal nerve territory

- See also “Clinical features of acute compartment syndrome.”

- Often involves injury to the deep peroneal (fibular) nerve

- Treatment: fasciotomy (see “Treatment of acute compartment syndrome”)

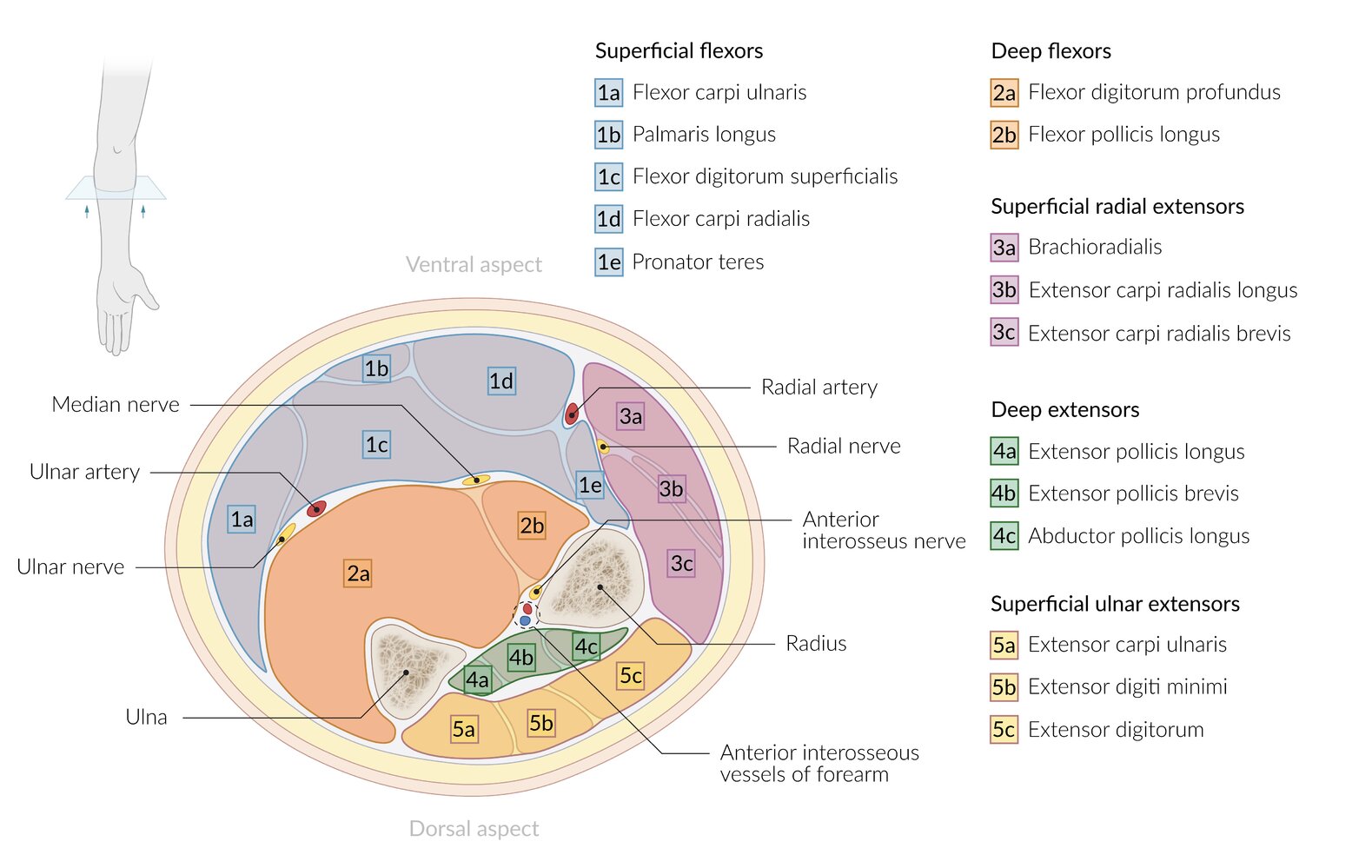

Forearm compartment syndrome [3][5][6]

- Prevalence: second most common type of ACS [4]

-

Etiology

- Most commonly caused by fractures of the wrist, forearm, or distal arm, e.g.: [5]

- Distal radial fracture (more common in adults)

- Supracondylar fracture of the humerus (more common in children)

- See also “Etiology of acute compartment syndrome."

- Most commonly caused by fractures of the wrist, forearm, or distal arm, e.g.: [5]

-

Clinical features [2]

- Most commonly involves the volar compartment

- Pain: with passive finger extension

- Motor: weak finger flexion

- Sensory: loss of sensation/parasthesia in the median nerve and/or ulnar nerve distributions

- See also “Clinical features of acute compartment syndrome.”

- Most commonly involves the volar compartment

- Treatment: fasciotomy (see “Treatment of acute compartment syndrome”)

Others

- Hand compartment syndrome: Etiologies include trauma, high-pressure injection, and IV infiltration. [7]

- Foot compartment syndrome: Etiologies include crush injuries, falls from height, and high-velocity accidents. [8]

- Gluteal compartment syndrome: Etiologies include pelvic trauma and prolonged immobilization (e.g., during surgery). [9]

Approach [1][3][10]

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings but is typically confirmed with early measurement of compartment pressures.

- Perform serial clinical examinations in all patients with risk factors for acute compartment syndrome.

- Measure compartment pressures in patients with clinical features concerning for acute compartment syndrome.

- Consider laboratory and imaging studies to determine the etiology and assess for complications.

In patients with obvious clinical features of compartment syndrome, consider forgoing diagnostics and proceeding immediately to urgent fasciotomy. [2]

Invasive compartment pressure measurement [1][3][10]

- Indication: suspected ACS with equivocal clinical findings

- Contraindications: no absolute contraindications [2]

-

Technique [2]

- Equipment: Multiple systems with similar accuracy are available; follow local protocols. [11]

- Measure pressure in the compartment of concern and all adjacent compartments. [12][13]

- Serial measurements are recommended if pressures are normal but clinical concern for ACS persists.

-

Findings: The following support a diagnosis of ACS. [1][3][10]

- Intracompartmental pressure ≥ 30 mm Hg

- Delta pressure≤ 30 mm Hg (ΔP = diastolic blood pressure - intracompartmental pressure)

- Rising or sustained elevation of compartment pressure

- Complications: infection, bleeding, tissue injury [2]

Critical pressure thresholds for performing fasciotomy are not absolute; always consider clinical findings when making management decisions.

Additional studies [1][3][10]

Laboratory and imaging studies are not used for diagnostic confirmation but may help identify the underlying cause of ACS or associated complications. [2]

-

Laboratory studies: to assess for rhabdomyolysis and crush syndrome and other potential complications

- CBC

- CMP (including renal function tests)

- CPK

- Serum and urine myoglobin

- Coagulation panel

- Urinalysis

-

Imaging studies

- X-rays: to identify associated fractures

- Ultrasound with and without Doppler: to rule out deep vein thrombosis and evaluate arterial blood flow

Do not rely on noninvasive perfusion assessment (e.g., pulse oximetry, arterial Doppler) to assess for ACS because arterial blood flow may be detectable even in advanced compartment syndrome. [1]

| Differential diagnoses of compartment syndrome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Features | Acute compartment syndrome | Deep vein thrombosis | Acute limb ischemia | Rhabdomyolysis |

| History |

|

|

|

|

| Clinical features |

|

|

|

|

| Diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

|

|

Others

- Cellulitis

- Peripheral artery disease

The differential diagnoses listed here are not exhaustive.

Immediate management [3][10]

- Stabilize as needed (e.g., IV fluid resuscitation and transfusion for hemorrhagic shock).

- Obtain immediate surgical consultation (e.g., trauma, orthopedic, or vascular surgery) for all suspected cases.

- Initiate supportive care to optimize tissue perfusion and oxygenation.

- Perform serial clinical examinations and/or invasive compartment pressure monitoring.

- Disposition

- Likely or confirmed ACS: Proceed to emergency fasciotomy.

- All other patients: Admit to an ICU or observation unit until ACS has been ruled out.

ACS is a surgical emergency and requires emergent fasciotomy, as irreversible tissue necrosis and functional impairment can occur within 4–6 hours of onset.

Supportive care [3][10]

- Remove constrictive dressings, splints, and devices.

- Provide systemic analgesia. [10]

- Place the limb at the level of the heart.

- Reduce displaced fractures.

- Administer supplemental oxygen. [14]

Avoid elevated positioning of the limb, as this may worsen ischemia by reducing blood flow.

Surgical treatment [3][4][10]

- Indications: strongly suspected or confirmed acute compartment syndrome

- Contraindications: late ACS with evidence of irreversible intracompartmental damage [10][15]

-

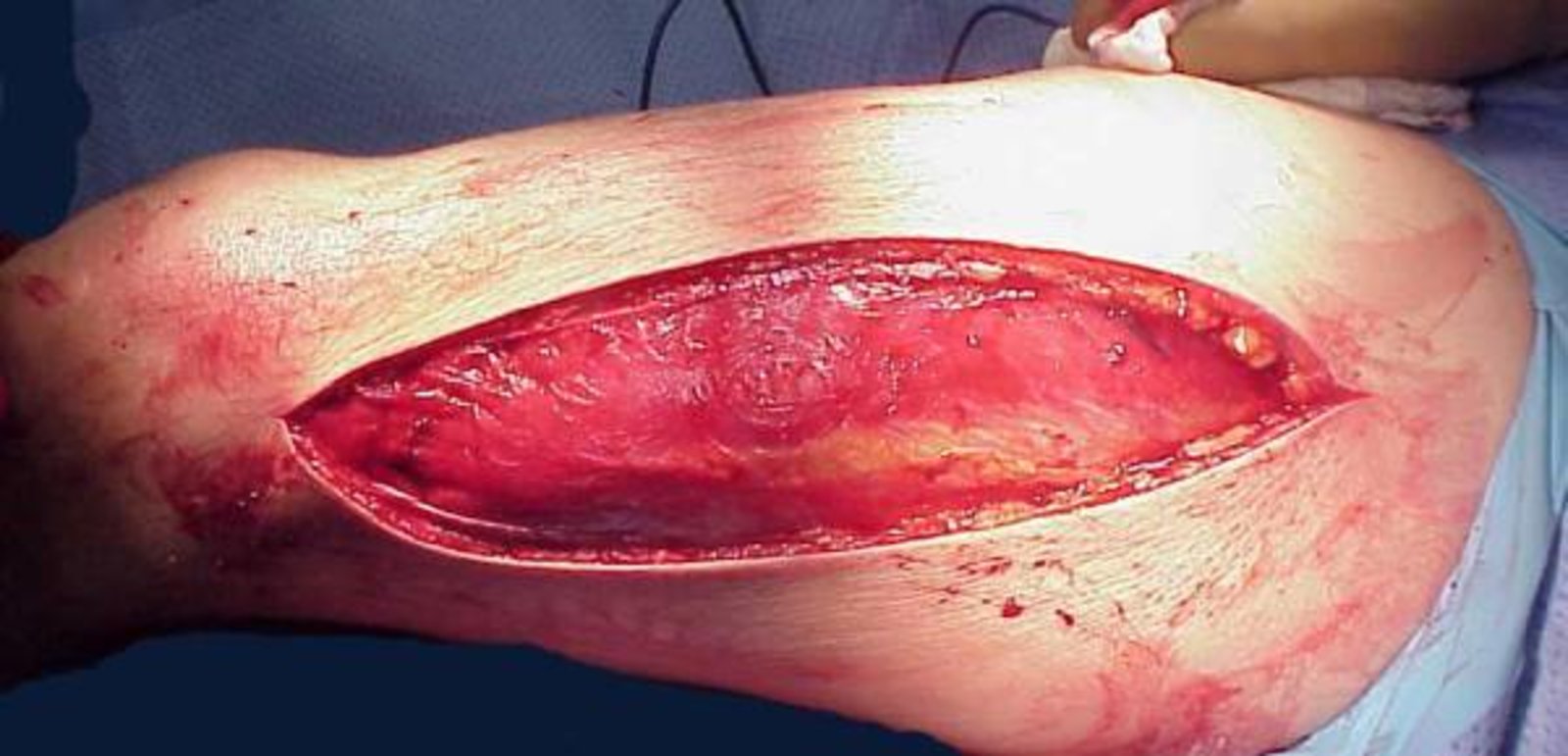

Techniques

-

Fasciotomy: incision(s) in the skin and fascia to relieve compartment pressure and restore perfusion

- Perform emergently to prevent irreversible injury.

- Postoperative wound treatment: usually left open for delayed primary closure [4][10]

- Escharotomy: incision of circumferential compressing burn eschar

- Fibulectomy: removal of the fibula to decompress all four compartments of the leg [4]

-

Fasciotomy: incision(s) in the skin and fascia to relieve compartment pressure and restore perfusion

- Muscle and soft tissue necrosis with a higher risk of infection [4]

- Nerve lesions (esp. the tibial nerve and peroneal nerve) with sensory and motor deficits or paralysis

- Rhabdomyolysis with potential crush syndrome

- Malunion fractures

-

Volkmann ischemic contracture

- Definition: permanent shortening of the forearm muscles resulting in a claw-like deformity of the fingers, hand, and wrist

- Etiology

- Undiagnosed compartment syndrome (especially due to tight casts/bandages and crush injuries)

- Supracondylar humeral fracture

- Pathophysiology: blood vessel (e.g., brachial artery) or nerve (e.g., radial nerve) damage ; (e.g., due to forearm fracture, repositioning of the bones, restrictive cast) → sustained ischemia and necrosis → fibrosis and contracture of the forearm flexor muscles →atrophy of the flexors of the hand and fingers

- Clinical features

- Thumb adduction

- Flexed fingers and wrist

- Pain on passive extension of affected fingers and wrist

- Elbow flexion and forearm pronation

- Decreased sensation

- Intrinsic minus deformation (advanced cases): overextended metacarpophalangeal joints and flexed interphalangeal joint

- Diagnostics: clinical diagnosis

- Differential diagnosis: Dupuytren contracture

- Treatment

- Conservative: physical therapy, dynamic elbow splint

- Surgical: tendon transfer procedures, nerve decompression (severely impaired hand function)

-

Rebound compartment syndrome

- Onset: occurs 6–12 hours after surgical reperfusion

- Etiology: increased capillary permeability and edema, often due to insufficient fasciotomy incisions

We list the most important complications. The selection is not exhaustive.

The prognosis depends on the amount of time that has elapsed prior to performing the fasciotomy: [4]

- ≤ 4–6 h: almost complete recovery

- 6–12 h: first necroses

- ≥ 12 h: necroses; little or no return of function