Introduction

Acute HIV infection represents the earliest stage following the acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus targeting CD4+ T lymphocytes with resulting immune system impairment. This stage typically occurs 2-4 weeks post exposure and is marked by rapid viral replication, high levels of viremia, and a significant reduction in CD4+ T-cell counts. It is often accompanied by nonspecific symptoms that mimic other viral illnesses, making diagnosis challenging. For these reasons, acute HIV infection is a pivotal period for viral dissemination and heightened transmission risk.

Epidemiology and transmission

HIV infection remains a global public health challenge, with >40 million people living with HIV worldwide. HIV-1 is responsible for most of the infections worldwide (and nearly all cases in the United States), although HIV-2 infection can sometimes occur (namely in West Africa). Despite advancements in treatment and prevention, certain populations remain disproportionately affected. Key risk groups include men who have sex with men, individuals with multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, IV drug users, and those living in high-prevalence regions (eg, sub-Saharan Africa). Transmission occurs primarily through the exchange of body fluids, with the most common routes of transmission including sexual, parenteral, and vertical (mother-to-child) transmission.

The risk of transmitting HIV is highest during acute infection due to a combination of very high viral loads and because many individuals are unaware of their acute infection given the nonspecific symptoms (discussed below). Transmission risk can be minimized with effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) and behavioral modifications that include safe sexual practices, needle exchange programs, and pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Pathogenesis

On transmission of HIV-1 (rarely HIV-2), the virus rapidly replicates and disseminates throughout the body, targeting CD4+ T lymphocytes and establishing infection in lymphoid tissues. The acute phase is characterized by a surge in viremia and a significant drop in CD4+ T-cell count. The immune system begins to mount a response, leading to partial control of viral replication during early infection. However, the virus continues to replicate at lower levels and individuals remain highly infectious. The HIV viral life cycle is discussed in detail in a separate article.

Clinical presentation

Acute HIV infection, also known as acute retroviral syndrome, causes symptoms in approximately 50%-90% of infected individuals. Symptoms typically develop 2-4 weeks following exposure, last 1-2 weeks, and include the following:

- Fever is present in the majority of symptomatic patients with acute HIV infection and may be persistent or intermittent.

- Nontender lymphadenopathy is common and involves multiple sites, such as the cervical, axillary, and occipital regions.

- Pharyngitis often mimics that of infectious mononucleosis, presenting with sore throat and erythema but typically without tonsillar exudates.

- A generalized, nonpruritic maculopapular rash commonly involves the trunk and face and can extend to the palms and soles, a feature that distinguishes it from other viral exanthems.

- Painful oral ulcerations are a distinctive feature, presenting as shallow ulcers with a white base, commonly found on the buccal mucosa, tongue, or soft palate.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps, may occur and are sometimes accompanied by anorexia or mild dehydration.

- Generalized symptoms such as myalgias, arthralgias, weight loss, and night sweats are frequent and contribute to the systemic nature of acute HIV infection.

- Neurologic symptoms may be seen, with headaches being common and aseptic meningitis occurring in up to 25% of cases. The meningitis is typically mild, but associated symptoms such as photophobia, nuchal rigidity, or cranial nerve involvement may occasionally be observed.

Patients often describe these symptoms as a "flu-like" or "mono-like" illness. However, many individuals experience minimal or no symptoms during acute infection, which can contribute to underdiagnosis with missed opportunities for early treatment and prevention of transmission.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests

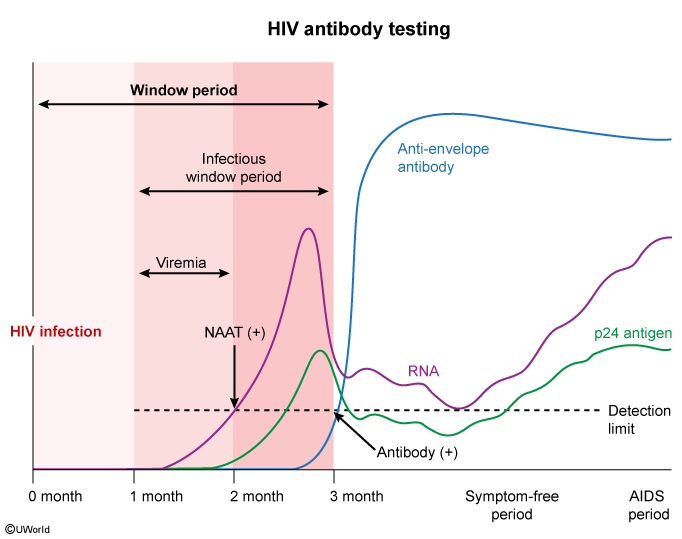

Nonspecific laboratory findings during acute HIV infection include transient lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes. Diagnosing acute HIV infection can be challenging due to the vague nature of symptoms and the timing of antibody production

- Fourth-generation HIV screening test: Detects both HIV-1/2 antibodies (eg, anti-envelope) and the p24 antigen, allowing earlier detection of infection (as early as 15-20 days post exposure).

- HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay: Distinguishes between HIV-1 and HIV-2 following a positive fourth-generation test.

Positive results on both tests confirm HIV (1 or 2).

However, there is a "window period" in acute HIV in which the cell-mediated and humoral antibody responses against the virus are not yet fully activated. During this period, patients may have extremely high levels of viral replication (~5 million RNA copies/mL) but negative or undetectable antibodies. In such cases, HIV-1 nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is crucial as it can detect viral RNA directly (as early as 10 days post exposure). A classic laboratory pattern in this period may include a positive NAAT (ie, positive "viral load" by PCR) and p24 antigen with a negative serologic response (negative HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody). For this reason, if acute HIV is suspected but the antigen/antibody tests are negative or indeterminate (including positive screening test with negative antibody differentiation immunoassay), NAAT can confirm the diagnosis.

Detection of early infection is becoming increasingly common due to increasing use of sensitive immunoassays.

Screening for other infections

Patients with a new diagnosis of HIV undergo testing for exposure or immunity to several pathogens, including hepatitis viruses A, B, and C; tuberculosis; and sexually transmitted infections

Those who have no immunity to hepatitis A or B require vaccination.Management

Early initiation of ART is recommended for all individuals diagnosed with HIV infection, regardless of CD4+ T-cell count or clinical stage. In the past, ART initiation was often postponed for patients with early HIV (eg, CD4 >500/mm3) due to the toxicity of long-term treatment and the lower risk of HIV-related complications early in the disease course. However, current ART medications are well tolerated, and early ART initiation is associated with significant reductions in long-term HIV-related complications, including:

- Immunosuppression: Patients who start ART with low CD4 counts (eg, <200/mm3) often cannot fully reconstitute CD4 levels to >500/mm3. However, those who initiate ART at higher CD4 counts often restore CD4 counts to normal.

- Inflammatory diseases: HIV causes significant immune stimulation and leads to chronically high levels of proinflammatory cytokines. This drives several of the long-term complications of HIV infection, including cardiovascular disease, renal disease (eg, HIV-associated nephropathy), liver disease, neurologic disease (eg, HIV-associated neurologic disease), and malignancy. Early ART initiation reduces the amount of time that patients are exposed to proinflammatory cytokines and, therefore, reduces risk for inflammatory complications.

- Oncogenic viral reactivation: ART reconstitutes cell-mediated immunity, which lowers the risk of oncogenic viral reactivation (eg, human herpesvirus-8 [HHV-8], human papilloma virus [HPV], Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]) and the subsequent development of AIDS-defining malignancies (eg, Kaposi sarcoma, invasive cervical cancer, lymphoma).

Early ART initiation also dramatically reduces the risk of HIV transmission to others. Patients with fully suppressed viral loads are considered noninfectious and cannot transmit the virus to sexual partners. Regimens usually consist of a combination of at least 3 antiretroviral medications from at least 2 different classes

Initial regimens are tailored to individual patient factors, including resistance testing, potential side effects, comorbid conditions, and patient preferences. Specifics of ART selection are discussed in a separate article.Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

HIV seroconversion following occupational exposure is rare and occurs primarily with percutaneous injury (eg, needlestick). PEP is recommended following percutaneous exposure or exposure of mucous membranes or nonintact skin to blood or other potentially infectious body fluids (eg, semen, vaginal secretions, other fluids with visible blood) from a source patient who is HIV positive

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

PrEP with once-daily tenofovir plus emtricitabine can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition by >90% and is generally offered to those at substantial risk for new HIV infection due to:

- Sexual behaviors: HIV-positive partner with detectable viral load; men who have sex with men and individuals from high-prevalence areas (eg, sub-Saharan Africa) with recent bacterial sexually transmitted infection, sex in exchange for money, inconsistent condom use, or a high number of partners

- Injection drug use: HIV-positive injecting partner; sharing of injecting equipment

PrEP is not recommended for patients at lower risk for HIV infection as the treatment is costly and can be associated with significant side effects (eg, renal insufficiency, osteoporosis).

Prognosis

The prognosis of HIV infection has significantly improved with the widespread use of effective ART. Early detection and treatment can preserve immune function and prevent many of the complications associated with HIV. By achieving viral suppression, patients can live near-normal lifespans with proper treatment adherence. Early initiation of ART can limit the size of the viral reservoir and slow disease progression. Lifelong adherence to ART is required to maintain viral suppression and prevent progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and development of malignancies.

Differential diagnosis

The nonspecific symptoms of acute HIV infection can mimic other conditions, necessitating a thorough evaluation and consideration of various diagnoses.

Infectious mononucleosis

Infectious mononucleosis caused by EBV or cytomegalovirus (CMV) shares symptoms such as fever, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, and fatigue with acute HIV. These conditions may also involve mild hepatosplenomegaly, particularly in EBV-associated mononucleosis. However, distinguishing features include the presence of atypical lymphocytes on a peripheral smear, which are less commonly seen in acute HIV. Rash and mucocutaneous ulcers, which are more characteristic of acute HIV, are observed infrequently in EBV or CMV infections. Serologic testing for heterophile antibodies (positive in EBV) and specific viral antibody testing for CMV can aid in differentiation.

Influenza

Influenza frequently presents with sudden-onset fever, myalgia, and headaches, symptoms that overlap with acute HIV infection. However, influenza is more commonly associated with prominent respiratory symptoms (eg, cough). Significant lymphadenopathy and mucosal ulcerations, which are common in acute HIV infection, are usually absent in influenza. Confirmation of influenza can be achieved through rapid antigen or NAAT, which are particularly useful during seasonal outbreaks.

Herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection can cause fever, malaise, and mucocutaneous ulcers, resembling acute HIV infection. However, HSV ulcers are more localized and are often limited to specific regions, such as the oral or genital areas, rather than the generalized mucocutaneous involvement seen in acute HIV. Vesicular lesions that progress to painful ulcers are characteristic of HSV, and polymerase chain reaction or viral culture from the lesions can confirm the diagnosis.

Acute viral hepatitis

Acute viral hepatitis (eg, from hepatitis A, B, or C viruses) may present with fever, malaise, and elevated liver enzymes, findings that can overlap with acute HIV infection. However, they classically include jaundice, dark-colored urine, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain.

Secondary syphilis

Secondary syphilis may also cause fever, lymphadenopathy, and a diffuse maculopapular rash involving the palms and soles. However, it can present with additional skin manifestations such as condyloma lata, as well as vesicular or pustular lesions, which are not typical of acute HIV. Serologic testing for syphilis, including nontreponemal (eg, rapid plasma reagin) and treponemal (eg, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption) tests, differentiate between syphilis and acute HIV.

Pediatric HIV infection

Although primarily an adult disease, HIV can also occur in pediatric patients due to vertical transmission during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding. Infants and young children may present with nonspecific manifestations such as failure to thrive, developmental delays, persistent diarrhea, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and recurrent bacterial infections. Diagnosing acute HIV in infants is challenging due to the presence of maternal HIV antibodies, which can persist in the child's bloodstream for up to 18 months, rendering standard antibody tests unreliable. Virologic assays that detect HIV RNA or DNA are essential for early and accurate diagnosis in this population. Early initiation of ART in HIV-infected infants is crucial, as it significantly improves survival rates, reduces disease progression, and may limit long-term complications, including neurodevelopmental impairments

Summary

Acute human immunodeficiency infection marks the initial phase following human immunodeficiency virus acquisition, typically occurring 2-4 weeks post exposure. This period is characterized by rapid viral replication, high viremia, and often nonspecific "flu-like" symptoms (eg, fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis). Diagnosis during this stage can be challenging due to nonspecific symptoms and the "window period" in which antibodies are not yet detectable, but early detection is enhanced by fourth-generation human immunodeficiency tests and nucleic acid amplification testing. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy is crucial to control viral replication, preserve immune function, and reduce transmission risk.