Introduction

Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (AIFR) is a rapidly progressive infection of the paranasal sinuses, characterized by fungal invasion of the nasal mucosa and aggressive extension into adjacent structures such as the orbit and brain. The condition is typically seen in immunocompromised patients, and the most common pathogens include Mucorales and Aspergillus species. Even with prompt recognition and aggressive management, AIFR has high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Pathophysiology

AIFR occurs when environmental fungal spores are inhaled into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. In individuals who are immunocompetent, these spores are typically eliminated by innate immune defenses before they can germinate and cause disease. However, in hosts who are immunocompromised (eg, those with neutropenia, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus), the absence of immune protection allows fungal spores to germinate, invade the mucosa, and proliferate.

The infection begins in the paranasal sinuses but can rapidly extend to adjacent structures, including the orbit, palate, skull base, and brain. This aggressive spread is driven by the angioinvasive nature of Mucorales (eg, Rhizopus, Mucor) and Aspergillus species, which invade blood vessels, leading to thrombosis, tissue infarction, and necrosis. The resulting devitalized tissue promotes further fungal proliferation and deeper invasion, perpetuating a cycle of tissue destruction. Because of frequent orbital/intracranial involvement, AIFR is often described as rhino‑orbital‑cerebral sinusitis, with potential complications that include vision loss, cranial neuropathies, and neurologic deficits.

Mucormycosis is a specific form of AIFR that most commonly affects patients with diabetes mellitus, especially those with diabetic ketoacidosis

. It is usually caused by Rhizopus oryzae, a species of Mucorales that produces ketone reductase, an enzyme that facilitates growth in the acidic, glucose-rich environment characteristic of diabetic ketoacidosis.Risk factors

AIFR occurs almost exclusively in patients with severe immunodeficiencies, including:

- Diabetes mellitus.

- Neutropenia (eg, due to chemotherapy or hematologic malignancy.

- Solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- Prolonged immunosuppressive therapy: Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, calcineurin inhibitors, corticosteroids.

- Advanced AIDS.

Clinical presentation

Patients initially have symptoms that mimic acute bacterial sinusitis, including:

- Fever.

- Headache and/or facial pain, often unilateral and localized to the affected sinus.

- Nasal congestion and purulent nasal discharge.

As the infection spreads to contiguous structures (typically over the course of days), patients may develop the following clinical features:

- Black eschar (necrotic tissue) on the nasal turbinates, along with mucosal sloughing, ulceration, and, possibly, perforation.

- Nasal discharge containing blood and/or flecks of black eschar.

- Palatal pain and/or black eschar on the palate.

- Facial swelling and skin erythema (over the affected sinus.

- Periorbital swelling, proptosis, and visual impairment/loss (due to orbital invasion.

- Cranial neuropathies: Facial numbness, ophthalmoplegia, diplopia (due to nerve injury/ischemia.

- Mental status changes or coma (due to intracranial extension.

Diagnosis

Maintaining a high index of suspicion for AIFR is critical in any immunocompromised patient with severe sinus symptoms. Findings such as a black nasal eschar, ophthalmoplegia, and/or facial numbness should prompt urgent evaluation. Although imaging studies (eg, CT scan, MRI) are often used to assess for orbital, bony, or intracranial extension, a definitive diagnosis requires biopsy and histopathologic confirmation of fungal invasion.

Imaging

Images of the paranasal sinuses, orbit, and brain may be obtained with a CT scan, which is typically the initial imaging modality because it is most sensitive for detecting bony erosion. It may also reveal sinus opacification, mucosal thickening, and soft tissue swelling. MRI may also be obtained because it has superior soft tissue resolution and is particularly useful for evaluating for vascular invasion, cranial nerve involvement, and intracranial/orbital extension. However, although imaging can provide supporting evidence and details about the extent of disease, it is not specific enough to confirm the diagnosis of AIFR.

Biopsy and histopathology

Nasal endoscopy, which provides direct visualization of the nasal cavity, is a key diagnostic tool used to identify areas of mucosal ischemia and necrosis. Targeted biopsies are obtained from the affected regions and sent for histopathologic examination to confirm the diagnosis. Characteristic histopathologic findings include:

- Fungal hyphae invading the biopsied tissue.

- Angioinvasion, with fungal elements penetrating blood vessel walls, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue infarction.

- Extensive necrosis involving the mucosa and soft tissue.

- Minimal or absent inflammatory infiltrate, reflecting the host's immunosuppressed status.

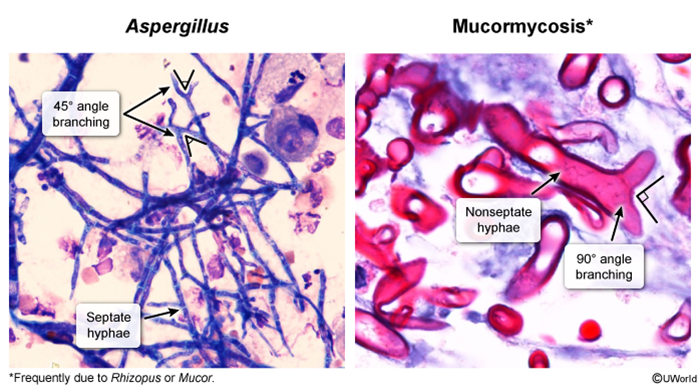

In addition, the 2 prominent fungal species responsible for AIFR can usually be distinguished by their histologic features

- Mucorales species (eg, Mucor, Rhizopus) appear as ribbon-like, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle (90-degree) branching.

- Aspergillus species (eg, Aspergillus fumigatus) show narrow, septate hyphae with acute-angle (45-degree) branching described as V-shaped branching.

Laboratory evaluation

Blood and nasal swab cultures are not reliable diagnostic tools because they rarely yield positive results. Fungal cultures are typically performed on biopsied tissue but are often slow-growing; treatment should not be delayed while awaiting results.

Differential diagnosis

- Bacterial sinusitis: Typically presents with headache/sinus pressure, purulent nasal drainage, and fever, but the infection responds well to antibiotics, does not progress rapidly, and does not cause tissue necrosis or invasion of adjacent structures.

- Chronic rhinosinusitis (with or without nasal polyps): Characterized by nasal congestion and obstruction, persistent purulent nasal discharge, anosmia, and facial pressure. However, the symptoms are chronic and noninvasive, lacking acute pain, fever, necrosis, or rapid progression.

- Allergic fungal sinusitis: An intense allergic response to fungal elements that colonize the sinuses. It leads to persistent nasal congestion and the accumulation of thick eosinophilic mucin. The condition develops gradually over years and does not cause necrosis.

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis: May cause sinusitis, epistaxis, and mucosal necrosis (eg, septal perforation) but is associated with systemic vasculitis, renal involvement, and positivity for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA. Manifestations arise over weeks to months, and bony erosions are not a typical feature.

- Malignancy (eg, nasopharyngeal carcinoma): Can cause nasal cavity or sinus obstruction with associated epistaxis and cervical lymphadenopathy, but tumors typically progress slowly and, although they may cause mass effect or bone remodeling, they rarely lead to rapid tissue necrosis.

Management

Treatment should be initiated urgently, with antifungal therapy initiated and emergency surgery performed.

Intravenous antifungal medications are administered based on the presumed fungal pathogen:

- Mucorales: Liposomal amphotericin B.

- Aspergillus: Voriconazole.

- In cases in which the specific pathogen is unclear: Broad-spectrum antifungal coverage (eg, combining amphotericin B and voriconazole.

Once the condition has clinically improved, patients can be transitioned to several weeks of step-down therapy with oral antifungal medication (eg, posaconazole.

In addition, urgent aggressive surgical resection of all necrotic tissue, including mucosa and underlying bone, is critical to decrease the fungal burden of disease, improve the penetration and effectiveness of antifungal medication, and provide direct exposure of the affected tissues (for disease monitoring. Orbital exenteration (removal of the entire orbit and its contents) and/or craniotomy is sometimes performed, but the morbidity of the procedure versus survival benefit remains unclear.

Complications

The complications of AIFR are often severe and life-threatening due to the angioinvasive nature of the causative fungi.

- Orbital/ocular complications include vision loss, typically due to optic nerve (CN II) involvement, and ophthalmoplegia resulting from invasion of the oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), and abducens nerve (CN VI.

- Intracranial complications may involve cavernous sinus thrombosis, ischemic stroke due to vascular occlusion, mycotic aneurysm, meningitis, brain abscess, and skull-based osteomyelitis.

- Bony destruction is also common, with erosion of the orbital, maxillary, and nasal bones, which can lead to significant facial deformity and functional impairment.

Prognosis

The prognosis of AIFR is poor. Mortality rates are high and can exceed 50%, particularly in patients with intracranial or orbital involvement. Early recognition, urgent surgical debridement, and timely antifungal therapy improve survival, although permanent complications such as vision loss or cranial nerve deficits are common.

Summary

Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is a life-threatening infection of the paranasal sinuses that typically affects individuals who are immunocompromised. The hallmark of the disease is rapid angioinvasion of the sinus mucosa, leading to vascular thrombosis, tissue necrosis, and extension to adjacent structures such as the palate, orbit, and brain. Imaging can provide supporting evidence, but biopsy and histopathology are required for diagnosis. Treatment involves a combination of surgical debridement and antifungal therapy, with aggressive management of underlying immunosuppressive conditions. Despite these measures, the prognosis is often poor.