Introduction

Alkylating agents are chemotherapy drugs that covalently bind alkyl groups to DNA, leading to base mispairing, DNA cross-linking, and, eventually, cell death. These agents are among the earliest anticancer drugs discovered. Their potential was first recognized after World War I, when exposure to mustard gas was observed to cause profound bone marrow suppression. Today, alkylating agents remain essential components of many chemotherapeutic regimens due to their broad cytotoxic activity.

Overview of chemotherapy

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease characterized by uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells that have acquired the ability to evade the body's normal control mechanisms (eg, resisting apoptosis, escaping immune surveillance).

Various strategies have been developed to treat cancer, including different combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Chemotherapy refers to the use of certain drugs (ie, chemical agents) to prevent further growth or induce death of these proliferating cells. Chemotherapy agents achieve this goal through different mechanisms that target various cellular components, including nucleic acids (eg, damaging DNA), cellular enzymes (eg, inhibiting enzymes required to synthesize essential cell proteins), and cellular structural components (eg, preventing the assembly of microtubules).

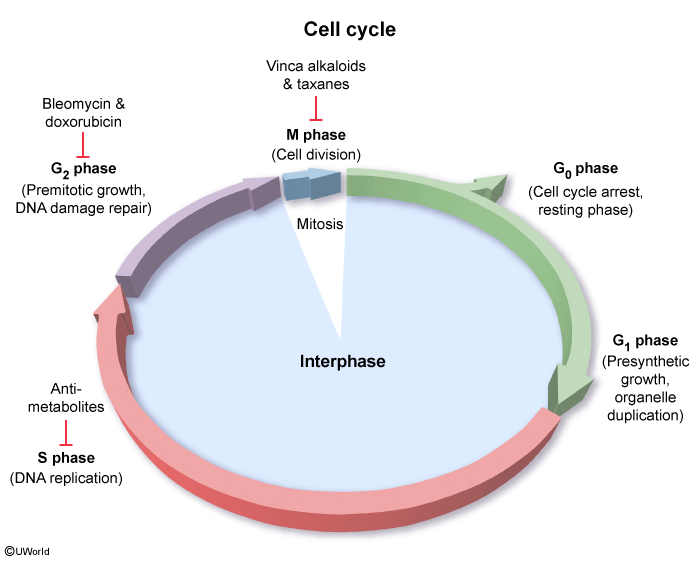

An important principle of cancer treatment involves the use of multiagent therapy (combining agents that have different mechanisms of action) to prevent resistance to single agents and increase the likelihood of cure. Chemotherapy agents can be categorized based on various features (eg, mechanism of action, chemical type); a common approach is to categorize the agents based on whether the mechanism of action depends on the cell-cycle status. Chemotherapy agents can therefore be broadly divided into cell cycle–specific and cell cycle–nonspecific agents.

Cell cycle–specific agents

Cell cycle–specific agents require cells to enter the cell cycle because these agents are effective only during certain phases of the cycle

- Antimetabolites: Antimetabolites are structured similarly to the substrates required during nucleotide assembly, interfering with biosynthesis. Antimetabolites work during the S phase (when DNA is duplicated), when they are substituted for the intended substrate, halting further DNA production. Agents include purine and pyrimidine analogues (eg, mercaptopurine, cytarabine, 5-fluorouracil) and folate analogues (eg, methotrexate).

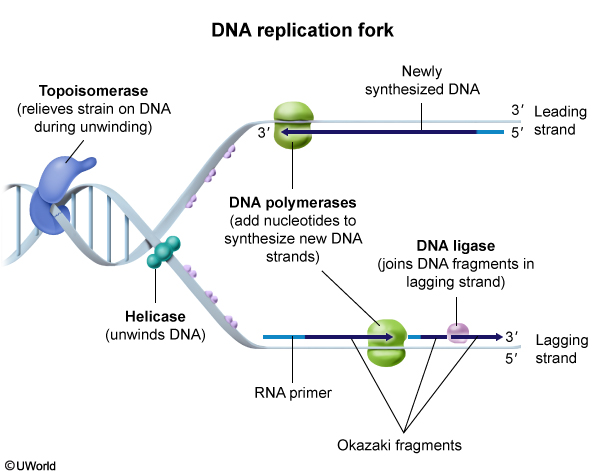

- Topoisomerase inhibitors: Topoisomerases are enzymes that transiently cut and reseal DNA to relieve supercoils that form when DNA unwinds during replication, repair, and transcription ( Topoisomerase inhibitors block these critical enzymes, which are particularly active during the late S and early G2 phases (when DNA replication errors are identified and repaired prior to cell division), leading to nucleic acid breaks and cell death. These agents can inhibit topoisomerase II (eg, etoposide) or topoisomerase I (eg, irinotecan).

figure 2

figure 2 - Microtubule inhibitors: These inhibitors are plant-derived agents that impair microtubule assembly and disassembly, which is required during the M phase (when a single cell splits into 2 via mitosis). Vinca alkaloids (eg, vincristine) inhibit microtubule assembly, and taxanes (eg, paclitaxel) inhibit microtubule disassembly.

Cell cycle–nonspecific agents

Cell cycle–nonspecific agents work during any phase of the cell cycle and may usually be administered in a large bolus dose. Examples include:

- Alkylating agents: Heterogeneous group of agents that form DNA strand cross-links via covalent attachment of alkyl groups, resulting in strand breakage and, ultimately, cell death.

- Antitumor antibiotics: Heterogeneous group of agents derived from microorganisms that have activity against the development of other types of living cells. Antitumor antibiotics commonly interfere with nucleic acids, preventing replication and transcription and triggering apoptosis. They can work by damaging DNA directly and/or indirectly. Agents include anthracyclines (eg, doxorubicin) and bleomycin.

This article focuses on alkylating agents, which form covalent bonds with DNA that cause strand cross-linking; despite this shared mechanism of action, individual agents differ in their specific indications and adverse effects and are divided into subclasses based on their chemical structures. Key alkylating agent subclasses include:

- Nitrogen mustards (eg, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, melphalan).

- Nitrosureas (eg, lomustine, carmustine). In addition to alkylation, these agents enhance cytotoxicity by performing carbamoylation, a chemical modification of enzymes that disrupts their function.

- Alkyl sulfates (eg, busulfan).

- Triazenes (eg, dacarbazine, temozolomide).

In addition, this article discusses platinum-based compounds (eg, cisplatin, carboplatin). These agents contain a platinum atom at their core and form covalent bonds with DNA, leading to cross-linking and apoptosis. Although they do not technically attach an alkyl group to DNA, they are frequently classified alongside alkylating agents due to their similar effects on DNA.

Clinical indications

Alkylating agents are essential components of chemotherapy regimens in a variety of hematologic and solid malignancies. Because they are cell cycle–nonspecific agents, they are commonly used in treating slow-growing cancers (eg, low-grade gliomas, indolent lymphomas). In addition, malignant cells with defective DNA repair mechanisms (eg, those harboring BRCA1 mutations that impair homologous recombination repair of double-stranded breaks) are particularly vulnerable to alkylating agents, particularly platinum-based compounds.

Nitrogen mustards

Nitrogen mustards are among the most frequently used alkylating agents. Cyclophosphamide is included in many regimens, including those used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomas, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. It is also included in conditioning regimens (ie, treatments that are used to prepare patients for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [HSCT]) and in managing autoimmune conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus). Ifosfamide is included in regimens for many solid tumors, including testicular cancer, osteosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Melphalan is used in conditioning regimens prior to HSCT for various hematologic malignancies (eg, multiple myeloma).

Nitrosureas

Lomustine and carmustine readily penetrate the blood-brain barrier and are used in managing various CNS tumors.

Alkyl sulfates

Busulfan is primarily a component of conditioning regimens prior to HSCT.

Triazenes

Temozolomide readily penetrates the CNS and is used to treat several types of CNS tumors (eg, astrocytomas, glioblastoma multiforme). Dacarbazine is included in the management of metastatic malignant melanoma and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Platinum-based agents

Cisplatin and carboplatin are used in managing a wide variety of malignancies, including lung, bladder, testicular, ovarian, and head and neck cancers.

Adverse effects and monitoring

Alkylating agents, like other chemotherapeutic agents, cause adverse effects on normal cells, particularly those that undergo rapid division normally. General adverse effects include myelosuppression (ie, dose-limiting neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia), gastrointestinal toxicity (eg, mucositis, nausea), and alopecia. Routine monitoring (eg, serial complete blood counts) and supportive care (eg, transfusions, antinausea medications) are essential. Patients are closely monitored for signs of infection with a low threshold for obtaining blood cultures and initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Alkylating agents and other drugs that cause direct DNA damage can significantly increase the risk for developing a secondary malignancy (by causing nonmalignant cells to acquire new mutations via erroneous DNA repair). Alkylating agents are also gonadotoxic, and treatment with these drugs increases the risk for infertility.

Nitrogen mustards

- Hemorrhagic cystitis: Cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are metabolized by the kidneys into acrolein, which is then excreted in the urine. Acrolein is toxic to uroepithelial cells and can cause cell death and necrosis with prolonged exposure. This can cause inflammation and bleeding at the bladder lining (ie, hemorrhagic cystitis). The risk for hemorrhagic cystitis can be reduced with aggressive hydration and frequent voiding to reduce contact time within the uroepithelium. In addition, coadministration with mesna (2-mercaptoethanesulfonate), a sulfhydryl compound that binds and inactivates the toxic metabolites in the urine, is protective. Serial urinalysis to assess for hematuria is recommended during treatment.

- Bladder malignancy: The toxic effects of acrolein also increase the risk for malignant transformation.

- Neurotoxicity: Approximately 25% of patients receiving ifosfamide can develop encephalopathy.

Busulfan (alkyl sulfate)

- Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome: Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome is a life-threatening complication of HSCT and is characterized by endothelial cell injury that triggers activation of the coagulation pathway, leading to hepatic sinusoidal vasoocclusion and liver necrosis. The risk is significantly elevated in patients undergoing conditioning with certain alkylating agents, particularly busulfan. Close monitoring of fluid balance and liver function testing should be performed during treatment.

- Pulmonary toxicity: Pulmonary toxicity can occur in a small percentage of patients who receive busulfan. This condition appears to be related to damage to pneumocytes with subsequent fibrosis. The risk can be reduced by careful pharmacokinetic monitoring during treatment.

Platinum agents

- Renal injury: Cisplatin is most commonly associated with nephrotoxicity. The risk is cumulative with continued exposure but can be reduced with aggressive hydration during treatment. Renal function (eg, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine) should be closely monitored.

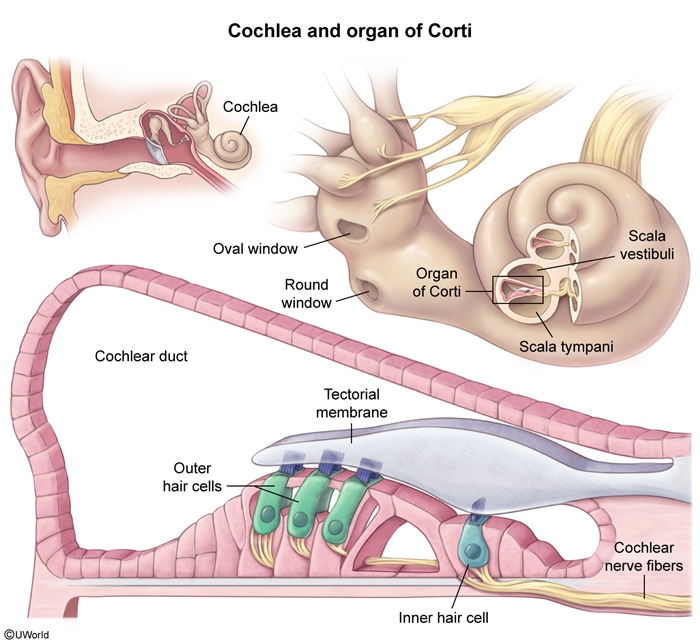

- Ototoxicity: Hearing loss and other neurotoxic effects (eg, peripheral neuropathy, CNS toxicity) are more common with cisplatin than carboplatin. Ototoxicity typically manifests as irreversible, bilateral, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss often accompanied by tinnitus and/or imbalance. The exact mechanism of injury is unclear, but it results in neurotoxicity and death of the outer hair cells in the organ of Corti ( Ototoxicity is dose dependent; therefore, monitoring protocols allow early detection and alteration of the chemotherapeutic regimen, if needed.

figure 3

figure 3

Summary

Alkylating agents are chemotherapy drugs that covalently bind alkyl groups to DNA, leading to base mispairing, DNA cross-linking, and, eventually, cell death. Alkylating agents are essential components of chemotherapy regimens in a variety of hematologic and solid malignancies. Individual agents have unique adverse effects that require careful monitoring.