Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a progressive decline in memory, cognitive function (eg, executive function, visuospatial ability, language), and behavior.

Risk factors

AD is associated with several modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors

- Age: Age is the greatest risk factor, with the incidence doubling every 5 years after age 65.

- Family history: Having a close relative with AD increases the risk.

- Genetics:

- Late-onset AD (age >65) is associated with the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene which is involved in cholesterol homeostasis and neuronal repair in the brain. Inheritance of the ε4 allele (likely causing impaired amyloid beta clearance) is a well-established risk factor. Carrying one ε4 allele increases the risk 3-fold, and having two (ε4/ε4 homozygosity) significantly increases the risk 12-fold.

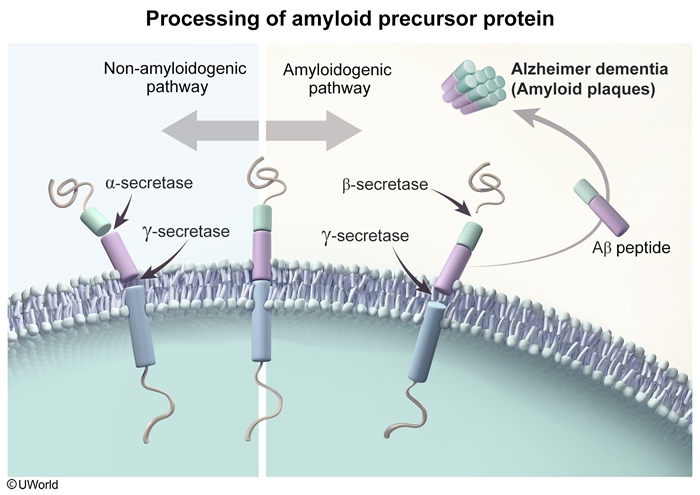

- Early-onset AD (age <65) accounts for <5% of cases; associated genetic mutations (autosomal dominant, highly penetrant) include amyloid-precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), and presenilin-2 (PSEN2).

- Down syndrome (trisomy 21) results from an extra copy of chromosome 21, where the APP gene is located; the extra copy of APP is thought to accelerate amyloid beta accumulation leading to early-onset AD.

- Cardiovascular risk factors: Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia, and smoking may contribute.

- Brain trauma: Severe brain trauma or repetitive head injury may increase the risk.

- Lifestyle factors: Physical inactivity, poor diet, and social isolation are associated with elevated risk. Conversely, maintaining physical activity, a healthy diet, and regular social engagement may have a protective effect.

Pathogenesis

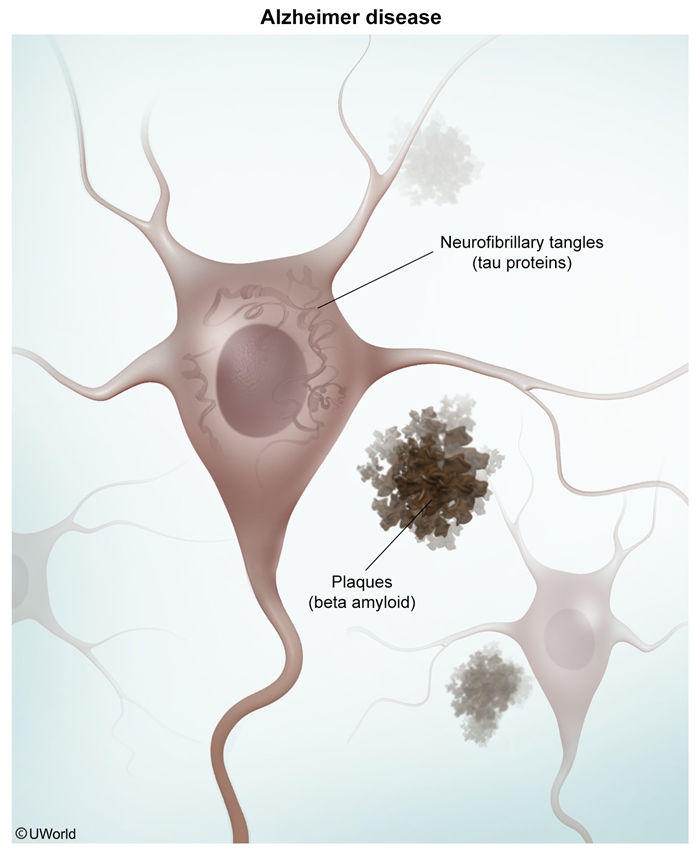

The exact pathogenesis of AD remains unclear, but it is hallmarked by the formation of extracellular neuritic plaques (amyloid beta accumulation) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (hyperphosphorylated tau proteins) that induce inflammation, leading to neurodegeneration

Amyloid beta accumulation

Amyloid beta results from altered cleavage of amyloid precursor protein

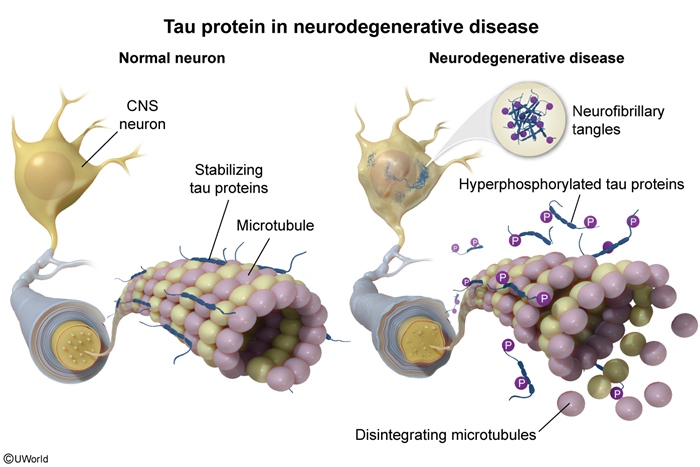

Tau hyperphosphorylation

Tau is a protein (primarily expressed in neuronal axons) that promotes microtubule assembly/stabilization. Hyperphosphorylation of tau (likely due to kinase activation by amyloid beta) causes microtubule instability that disrupts axonal transport and synaptic function. Hyperphosphorylated tau also aggregates into intracellular NFTs that are neurotoxic

Inflammation

Aggregates of amyloid beta and hyperphosphorylated tau trigger the activation of microglia (the brain's immune cells). Their subsequent release of inflammatory mediators results in neuroinflammation that causes further neuronal dysfunction and ultimately leads to apoptosis and cell death.

The pathogenesis of AD culminates in the diffuse loss of cortical neurons. Specifically, degeneration of neurons in the basal forebrain/nucleus basalis (the brain's major cholinergic output) contributes to memory loss and functional decline. Synaptic loss of cholinergic projections from the nucleus basalis to the neocortex results in dysfunction of target tissues involved in memory (hippocampus) and executive function (frontal cortex) that typify the cognitive decline of AD.

Pathology

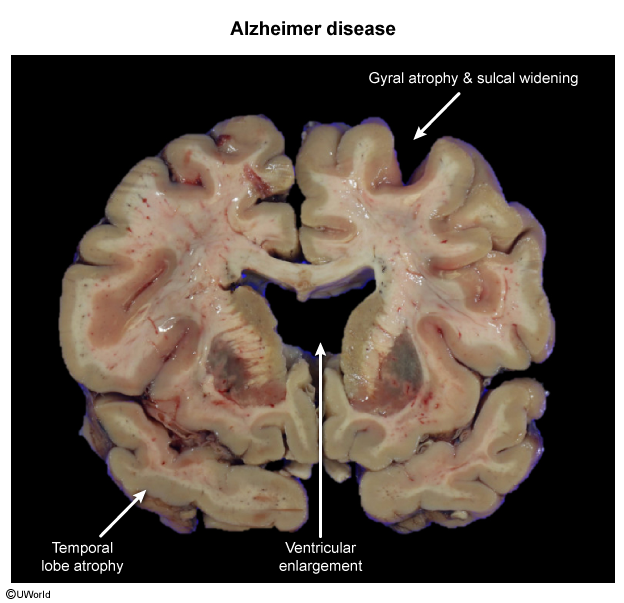

Gross

Macroscopic findings of brains with AD exhibit cortical atrophy with decreased brain weight, gyrus thinning, sulcus widening, and ventricular enlargement

Microscopic

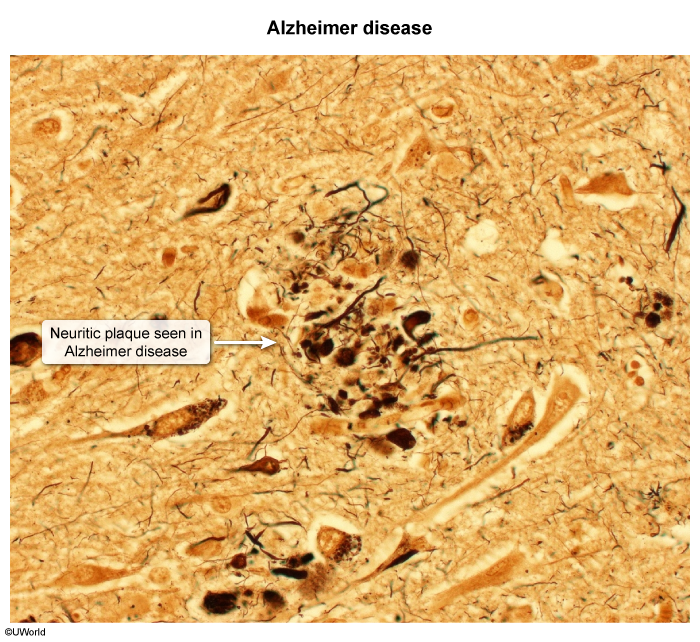

Hallmark pathologic features of AD include:- Neuritic (senile) plaques ( : Extracellular deposits of amyloid beta (Congo red–positive and birefringent) are found throughout the hippocampus and cerebral cortex.

image 2

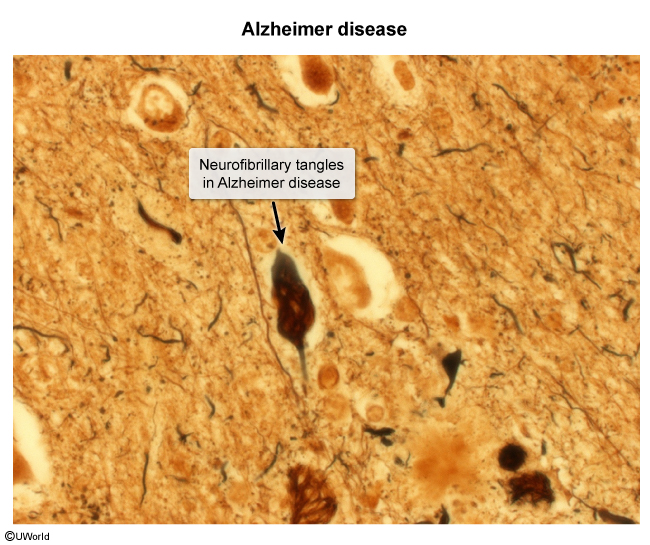

image 2 - Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) ( : Intracellular inclusions containing hyperphosphorylated tau proteins first appear in the medial temporal lobe and then spread to the hippocampus and neocortex. NFT density correlates with dementia severity.

image 3

image 3 - Other pathologic changes include synaptic loss, neuronal loss, and amyloid angiopathy.

Clinical presentation

AD is characterized by an insidious onset and gradual progression of cognitive impairment that interferes with everyday function (eg, activities of daily living [ADLs]). Although progression may vary, symptoms/signs of AD follow a similar pattern of early cognitive impairment followed by behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms

Symptoms/signs of AD include:- Memory: Impaired memory for recent events (processed by the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe) is typically the earliest and most prominent symptom. Examples include forgetting recent names/conversations, misplacing belongings, and difficulty learning new information. In contrast, remote/distant memories are usually spared until later stages.

- Executive function: Impairment in planning/organizing (eg, shopping, managing finances), problem-solving, attention, and judgment may be subtle in early disease. As AD progresses, executive dysfunction evolves into the inability to perform even simple tasks.

- Behavior and psychology: Neuropsychiatric symptoms are very common, particularly later in the disease, and are commonly worse in the evening (sundowning). More subtle symptoms are often described as personality changes (eg, apathy, social withdrawal, irritability). With progression, symptoms can range from anxiety and depression to psychosis (delusions, hallucinations, misidentification syndromes). Associated behavioral disturbances (eg, agitation, aggression, disinhibition, wandering, sleep disturbance) are difficult to manage and often lead to nursing home placement.

- Other domains

- Visuospatial ability: Identifying visual stimuli and interpreting spatial relationships (eg, trouble recognizing faces, getting lost in familiar surroundings) become impaired early and increase with AD progression.

- Language: Deficits in word finding, object naming, and speech comprehension are often subtle in early disease and progress to loss of verbal fluency and poverty of speech in late stages.

Other frequent findings include apraxia (difficulty performing learned motor activities), loss of insight, and olfactory dysfunction.

Noncognitive neurologic deficits, including motor signs (eg, gait disturbance, myoclonus), primitive reflexes (eg, grasp, snout), urinary incontinence, and seizures, are typically late findings; the presence of one of these findings at initial presentation should prompt consideration of diagnoses other than AD.

Diagnosis

Because confirmation requires histologic evaluation (usually at autopsy), AD is a clinical diagnosis. Criteria have been developed by professional societies (National Institute on Aging, Alzheimer's Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [DSM] of Mental Disorders) and include insidious onset and progressive course, exclusion of other etiologies, evidence of cognitive impairment in at least 2 domains (memory, executive function, visuospatial, language, behavior), and interference with daily function.

The diagnostic evaluation includes the following elements:

- Clinical history: A detailed cognitive history is essential due to AD's insidious onset, variable symptom emergence, and overlap with other disorders. Patients often minimize or hide their symptoms, so interviewing a family member/friend/caregiver is important to help assess the timing and degree of changes in cognitive function, behavior, and functional abilities.

- Cognitive testing: Screening tests include the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, a 30-point scale assessing many cognitive domains (delayed word recall, visuospatial/executive function, language, attention/concentration, orientation), which can detect subtle deficits and identify significant cognitive impairment (≤25/30, ≤24/30 with <12 years formal education). However, a dementia diagnosis cannot be made solely from a low score and should be interpreted in context with a thorough evaluation of cognitive domains, behavior, and daily function. Formal neuropsychologic testing, which evaluates multiple cognitive domains (eg, spatial memory, calculations, conceptualization, mental flexibility), is useful when the diagnosis is uncertain but unnecessary in most patients. Repeated assessments over time (eg, 9 months) are usually the most helpful.

- Neuroimaging: MRI of the brain is indicated to exclude alternate diagnoses (eg, cerebrovascular disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus [NPH]). MRI usually shows nonspecific generalized brain atrophy and may reveal the most characteristic findings of focal atrophy in the hippocampus and/or medial temporal lobe. Special imaging using radiotracers (eg, fludeoxyglucose-18–positron emission tomography [FDG-PET], amyloid PET, Tau PET) can help support the diagnosis of AD, differentiate it from other dementias, and track disease progression but are expensive and not widely available.

- Other laboratory testing: Patients being evaluated for cognitive impairment should undergo tests to rule out other conditions that cause cognitive decline, including vitamin B12 deficiency (vitamin B12 level, complete blood count) and hypothyroidism (TSH).

- Miscellaneous

- Biomarkers: Molecular biomarkers (low amyloid beta 42 peptide, high phospho-tau protein) identified on cerebrospinal fluid analysis can support the diagnosis of AD, but this test is not regularly performed (invasive).

- Genetic testing: Genetic testing is not routinely recommended. APOE testing does not add much to the predictive value of AD clinical criteria. Testing for APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations is reserved for early-onset AD. As with all gene testing, appropriate genetic counseling is important.

Differential diagnosis

- Normal aging: cognitive changes that normally occur with aging include mild declines in memory and the rate of information processing. Normal aging can be distinguished from AD (and other dementias) by relatively stable deficits and preserved daily function.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): describes measurable cognitive impairment that is worse than normal aging but does not yet meet the criteria for AD (eg, MCI does not impair everyday functioning). However, patients with MCI are at increased risk for progression to AD (~10% per year).

- Delirium: should be considered in any patient with cognitive impairment. Key features that distinguish delirium from AD include acute/subacute onset and fluctuation of consciousness.

- Depression: can cause significant cognitive impairment (eg, pseudodementia, dementia of depression) that may resemble AD. In contrast to AD, patients with dementia of depression usually have a subacute onset, emphasize cognitive deficits (vs minimize with dementia), and sometimes give poor effort ("I don't know.") rather than attempting to respond with incorrect answers.

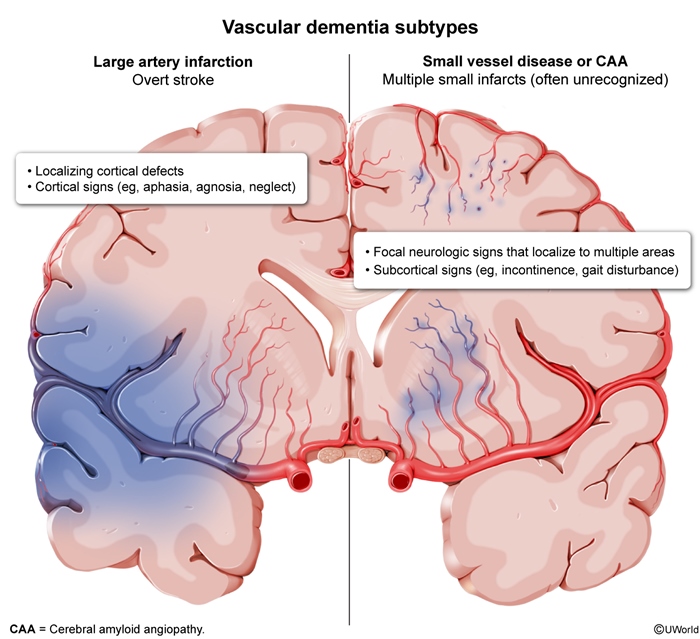

- Vascular dementia: is caused by stroke and/or small vessel cerebrovascular disease ( Distinguishing features include a stepwise decline in cognitive function, signs of vascular disease on neuroimaging (eg, infarcts, white matter changes), and evidence of stroke on examination (eg, aphasia, hemiplegia). Vascular risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking) are often present.

figure 4

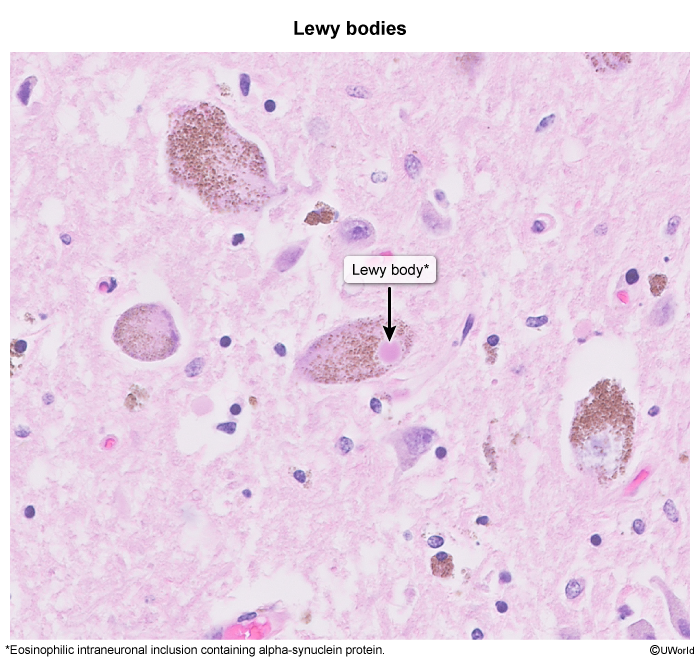

figure 4 - Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): is characterized by alpha-synuclein protein deposition in Lewy bodies, resulting in dementia ( Features that help differentiate DLB from AD include early-onset parkinsonism, visual hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Severe sensitivity to antipsychotics is also characteristic.

image 4

image 4 - Frontotemporal dementia (FTD): is a group of dementia disorders characterized by degeneration of the frontal and/or temporal lobes ( Unlike AD, FTD causes early changes in behavior and personality (behavioral variant) or early language impairment (primary progressive aphasia).

image 5

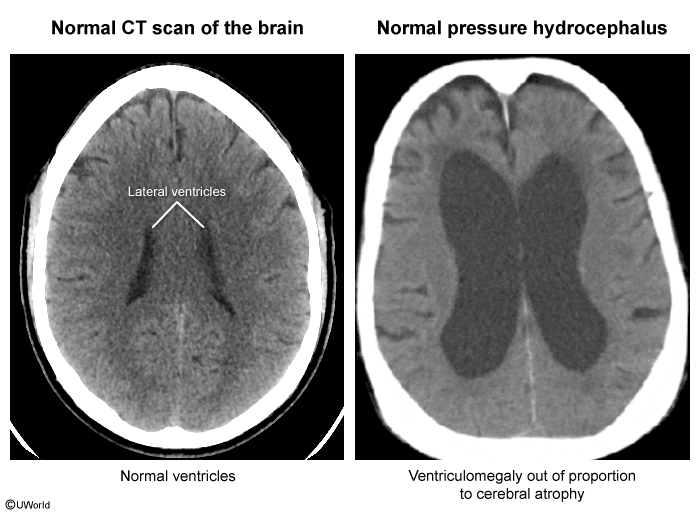

image 5 - Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH): can be idiopathic or secondary (eg, subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis). Like AD, NPH causes cognitive impairment; however, gait abnormalities typically precede dementia and urinary incontinence completes the classic triad ("wacky, wobbly, wet"). Imaging (MRI > CT) shows the hallmark finding of ventriculomegaly out of proportion to cortical atrophy (eg, sulcal enlargement) (

image 6

image 6

Management

No cure for AD currently exists. However, several treatment strategies can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life

:- Cholinesterase inhibitors: AD results in decreased acetylcholine synthesis (eg, nucleus basalis degeneration reduces choline acetyltransferase production). By inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, drugs such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine increase levels of acetylcholine at the synaptic cleft, which modestly improves cognitive function, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and ADLs in mild-to-moderate AD. Conversely, anticholinergic medications should be avoided.

- Memantine: NMDA receptors stimulate glutamate (the primary excitatory neurotransmitter). By blocking NMDA receptors, memantine reduces glutamate-induced excitotoxicity and resultant neuronal damage/death. Memantine (typically in combination with a cholinesterase inhibitor) modestly improves cognition, behavior, and ADLs in moderate to severe AD.

- Aducanumab: As a monoclonal antibody against amyloid beta, aducanumab reduces neuritic (amyloid beta) plaques. Although approved by the US FDA for mild AD, clinical benefits are unclear so its use is currently limited.

- Nonpharmacologic interventions: Cognitive rehabilitation, physical activity, and social engagement can help maintain cognitive function, improve mood and behavior, and enhance quality of life for patients with AD.

Prognosis

AD, like most neurodegenerative diseases, has a relentless progression. Life expectancy after diagnosis is typically 8-10 years but can range from 3-20 years, depending on individual factors (eg, age at onset, symptom severity, comorbidities). Death usually results from advanced debilitation (eg, dehydration, malnutrition, infection).

Summary

Alzheimer disease

is a neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects older adults and represents the most common cause of dementia. The exact etiology remains unclear, but it is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid beta and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins into neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, respectively. Diagnosis is clinical and requires a thorough assessment of cognitive function, behavior, and functional ability. Current treatment has little effect on progression and aims to maintain cognitive function, manage symptoms, and enhance quality of life.