Amyloidosis is a collective term for the extracellular deposition of abnormal proteins, in a single organ (localized amyloidosis) or throughout the body (systemic amyloidosis). The different subtypes of amyloidosis are classified according to the identity of the deposited proteins. The standardized naming convention dictates that the letter “A” for amyloidosis is followed by an identifier of the protein that forms the amyloid fibril deposits (e.g., AL for immunoglobulin light chain deposits). These abnormal proteins are produced as a result of various diseases. The most common form of systemic amyloidosis in developed nations is light chain amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis), which is associated with plasma cell dyscrasias such as multiple myeloma. The second most common systemic form, reactive amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis), is secondary to chronic inflammation and typically presents with nephrotic syndrome. Depending on which organs are affected, amyloidosis may also manifest with hepatomegaly, macroglossia, cardiac conduction abnormalities, and/or symptoms of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Abdominal fat or rectal mucosa biopsies are used to diagnose systemic amyloidosis. Target organ biopsy is more sensitive but less commonly required for definitive diagnosis because it presents a higher procedural risk. When stained with a Congo red dye, amyloid deposits in the biopsy sample exhibit an apple-green birefringence under polarized light. Management of amyloidosis is dependent on the specific type and is specialist-guided. In AL amyloidosis, chemotherapy with melphalan and corticosteroids may be used, and suitable patients may be referred for autologous HSCT. Treatment of the underlying disease is the mainstay of management for AA amyloidosis. Organ transplantation may also be an option for certain patients as directed by a specialist.

Definitions [1]

- Amyloid: insoluble protein or protein fragments

- Amyloidosis: extracellular aggregation and subsequent deposition of amyloid in various organs

Pathogenesis

- Accumulation of amyloid → cellular injury and apoptosis [2]

- Composition of amyloid:

- Fibrillar component (90–95% of amyloid): β-sheet fibrils

- Nonfibrillar component (5–10% of amyloid): usually the same in all types of amyloid (e.g., amyloid P component, glycosaminoglycans)

Classification [3]

- The standardized nomenclature convention for amyloidosis is “AX.”

- A denotes amyloidosis.

- X denotes the affected protein that comprises the fibrillar component.

- May also be classified as:

- Systemic amyloidosis or localized amyloidosis

- Acquired or hereditary amyloidosis

Overview

The following list is not exhaustive; > 15 types of systemic amyloidosis have been identified, each caused by a different protein. [1]

| Overview of systemic amyloidosis [1][4][5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected protein | Etiology | Characteristic features | |

| AL amyloidosis (light-chain amyloidosis or primary amyloidosis) |

|

|

|

| AA amyloidosis(reactive amyloidosis or secondary amyloidosis) |

|

|

|

| Aβ2M amyloidosis (β2-microglobulin amyloidosis or hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis) |

|

|

|

| ATTRmt amyloidosis (mutated transthyretin amyloidosis, ATTRv (variant) amyloidosis, or hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis) [8] |

|

|

|

| ATTRwt amyloidosis (wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis or senile cardiac amyloidosis) |

|

|

|

Approach to management [1][4]

Suspect systemic amyloidosis in patients with constitutional symptoms and multiple affected organs.

- Obtain tissue biopsy to confirm amyloid deposition and to identify the fibril type.

- Obtain baseline laboratory studies.

- Consider cardiac and imaging studies based on clinical suspicion of organ involvement.

- Obtain additional studies to identify the underlying cause.

- The goal of management is to suppress the amyloid precursor protein by treating the underlying disease.

- Treatment may include:

- Pharmacotherapy

- Organ transplantation

- Supportive care of complications, e.g.:

- Heart failure management

- CKD management

Management should be focused on treating the underlying disease, as this may stall disease progression. [1]

Diagnostics of amyloidosis [1][4]

Tissue biopsy

The type of tissue sample depends on the extent of disease and organ involvement. [10]

-

Tissue sample

- Target organ (e.g., of a kidney or a nerve): preferred in patients with single organ involvement

- Abdominal fat aspiration or rectal mucosa: preferred in patients with multiorgan and/or tissue involvement [3]

-

Methods

-

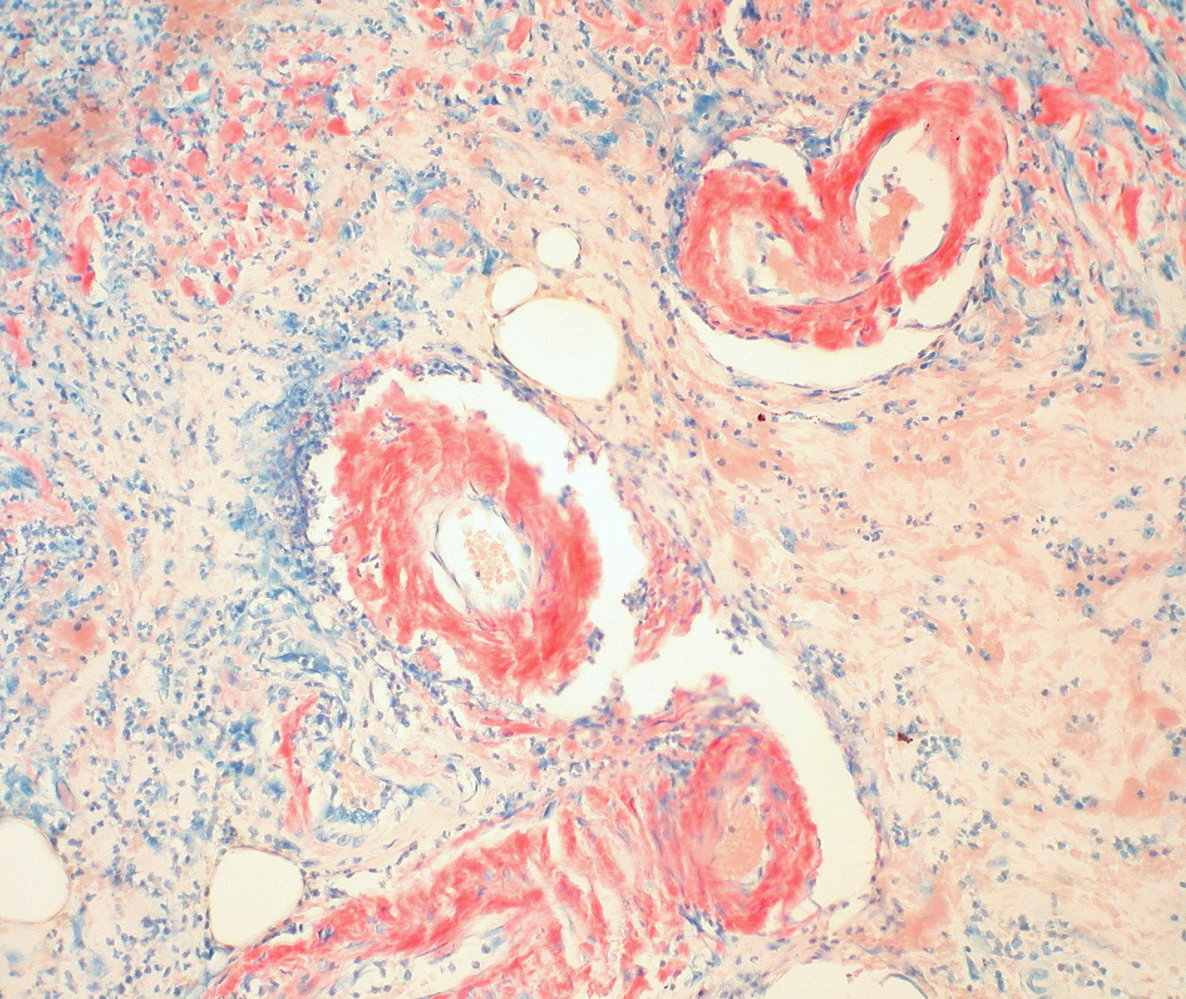

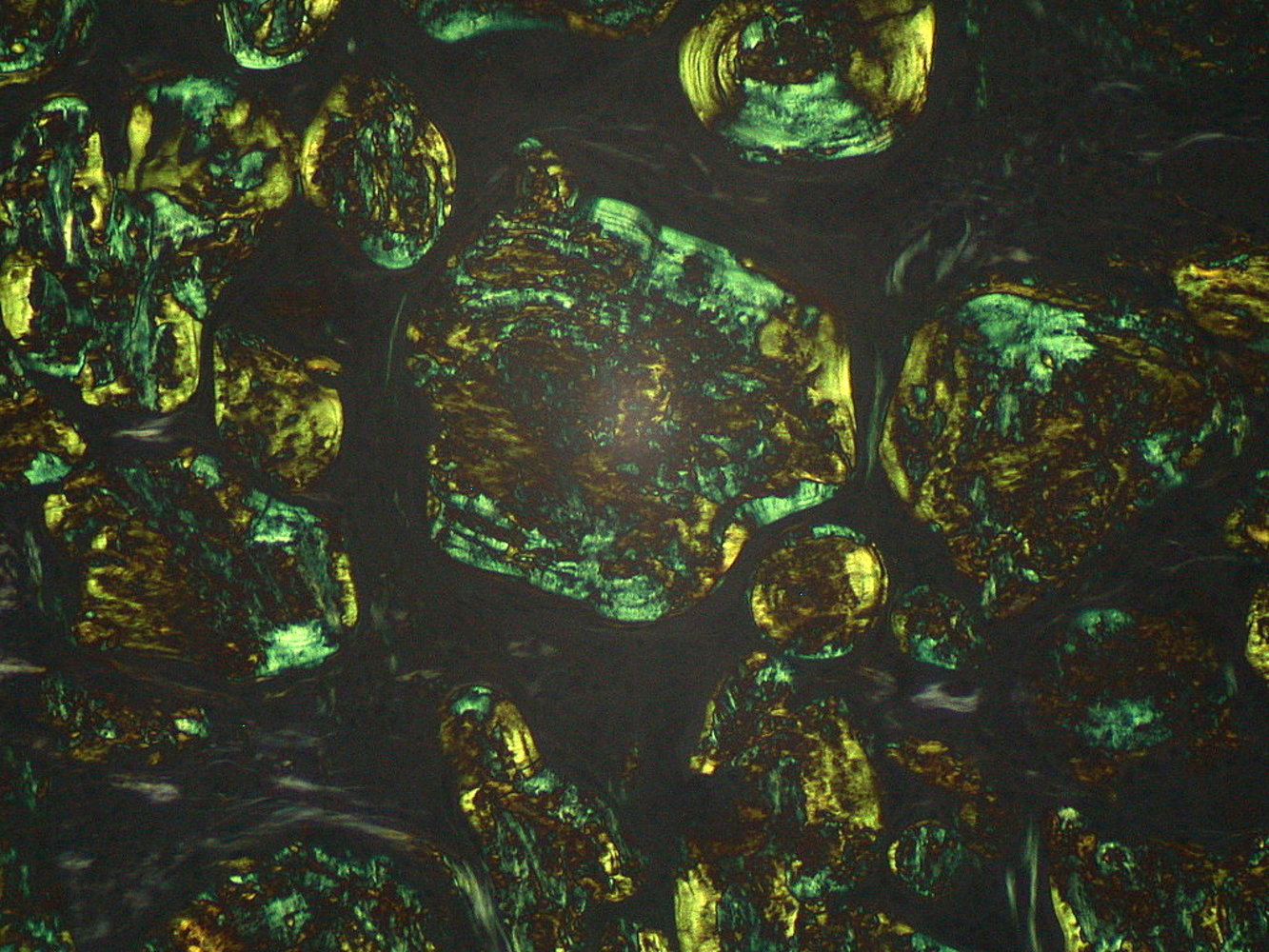

Congo red stain to confirm amyloid deposition

- Pink to red appearance under nonpolarized light

- Apple-green birefringence under polarized light

- Additional findings from an affected kidney may include deposits in glomerular mesangial areas (visible on H&E stain) and enlarged tubular basement membranes that can be identified via light microscopy. See “Amyloid nephropathy.”

- Immunohistochemistry or mass spectrometric analysis: for fibril typing and classification

-

Congo red stain to confirm amyloid deposition

After staining demonstrates amyloid deposition, diagnosis is confirmed by identifying the specific protein fibril in the amyloid deposits of the biopsied tissue sample.

Additional studies [1][4]

Additional studies should be obtained for risk stratification and to guide management decisions. Results will vary depending on the type and degree of end-organ involvement.

-

Laboratory studies

- BMP

- CBC

- Liver chemistries

- Coagulation studies

- Cardiac biomarkers: e.g., troponins, BNP

- Urinalysis

-

Cardiac studies: Consider in all patients to assess for cardiac involvement.

- ECG: may show low or inappropriately normal voltages

- Echocardiogram: may show diffuse atrial, ventricular, and septal thickening caused by amyloid depositions

- Cardiac MRI: can characterize disease severity in patients with known cardiac amyloidosis

- Radionucleotide scintigraphy: used to locate amyloid fibrils and monitor disease progression and/or response to therapy

-

Additional imaging studies: Consider in select patients to assess other organ involvement.

- CT chest: to assess for lung involvement

- CT abdomen: to assess for spleen or liver involvement, or lymphadenopathy

- MRI brain: to assess for leptomeningeal involvement

- Assessment of the underlying etiology: The approach depends on the specific type of amyloidosis.

Epidemiology [3]

Most common form of amyloidosis

Etiology [3][11]

Low-level expansion of a plasma cell dyscrasia (e.g., multiple myeloma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia)

Pathophysiology [3]

Increased production of the light chains of immunoglobulins → deposition of amyloidlight chain protein (AL protein) in various organs

Clinical features [3][5][12]

AL amyloidosis is a rare, but potentially severe disease that can affect any organ (with the exception of the CNS). [12]

- Skin: cutaneous ecchymoses around the eyes (raccoon eyes), combined with yellow waxy papules

- Heart: restrictive cardiomyopathy, HFpEF, atrioventricular block

- Kidney: nephrotic syndrome, type II renal tubular acidosis, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

- Tongue: macroglossia → obstructive sleep apnea

- Autonomic nervous system: autonomic neuropathy

- Gastrointestinal tract: malabsorption, hepatomegaly

- Hematopoietic system: bleeding disorders, splenomegaly [13]

-

Musculoskeletal system

- Carpal tunnel syndrome (may be bilateral)

- Shoulder pad sign

The combination of raccoon eyes, macroglossia, and the shoulder pad sign is highly specific for AL amyloidosis (but only present in ∼ 10 % of patients). [5]

Diagnostics [1][4][11]

Consult a specialist early (e.g., rheumatologist, hematologist).

- Obtain diagnostics of amyloidosis, including:

- Tissue biopsy

- Assessment of organ involvement, including ECG, cardiac imaging

- Obtain diagnostics for plasma cell dyscrasias to identify the underlying cause:

- Serum protein immunofixation (test of choice ): monoclonal light chain or whole immunoglobulin protein [3][4][4]

- Serum electrophoresis: monoclonal gammopathy

- Urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) with immunofixation: Bence-Jones proteins

- Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy: The presence of monoclonal plasma cells (comprise approx. 10% of aspirate sample) supports the diagnosis. [4]

- Apply diagnostic criteria for plasma cell dyscrasias (e.g., diagnostic criteria for multiple myeloma).

Suspect AL amyloidosis in patients with multiple affected organs (e.g., heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, nephrotic range proteinuria, peripheral neuropathy, hepatomegaly, and/or noninfectious diarrhea), and/or atypical MGUS or smoldering multiple myeloma.

Management [1][4]

Treatment options are based on the stage of the underlying disease (e.g., multiple myeloma staging), and level of end-organ damage (e.g., NYHA class for heart failure), and include:

- Control of the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia with:

- Chemotherapy: e.g., melphalan plus corticosteroids, thalidomide, bortezomib

- Autologous HSCT in eligible patients

- Supportive care for associated complications (e.g., heart failure, CKD)

The main goal of treatment is to inhibit plasma cells from producing light chains, which in turn reduces amyloid deposition and helps to facilitate organ recovery.

Prognosis [3][11]

- Rapidly progressive clinical course if left untreated

- Survival depends largely on the severity of cardiac and/or renal dysfunction at diagnosis.

- The median survival time without treatment is 1–2 years.

Etiology [3]

AA amyloidosis is secondary to a chronic disease, such as:

- Chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g., IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, vasculitis, familial Mediterranean fever)

- Chronic infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, leprosy, osteomyelitis)

- Malignancy (e.g., renal cell carcinoma, lymphomas)

Pathophysiology [3]

Chronic inflammatory process →↑ production of acute phase reactantSAA (serum amyloid-associated protein) → deposition of AA (amyloid-associated) protein in various organs

Clinical features [1][4][5]

- Kidney: nephrotic syndrome, type II renal tubular acidosis, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

- Adrenal glands: primary adrenal insufficiency

- Liver and spleen: hepatomegaly, splenomegaly

- Gastrointestinal tract: malabsorption

- Heart (rare): severe thickening of ventricular wall

The main feature of AA amyloidosis at diagnosis is renal dysfunction (e.g., CKD, nephrotic syndrome). Cardiac involvement is rare. [3][5]

Diagnostics [4][5][14]

Consult a specialist early (e.g., rheumatologist).

- Obtain diagnostics of amyloidosis including:

-

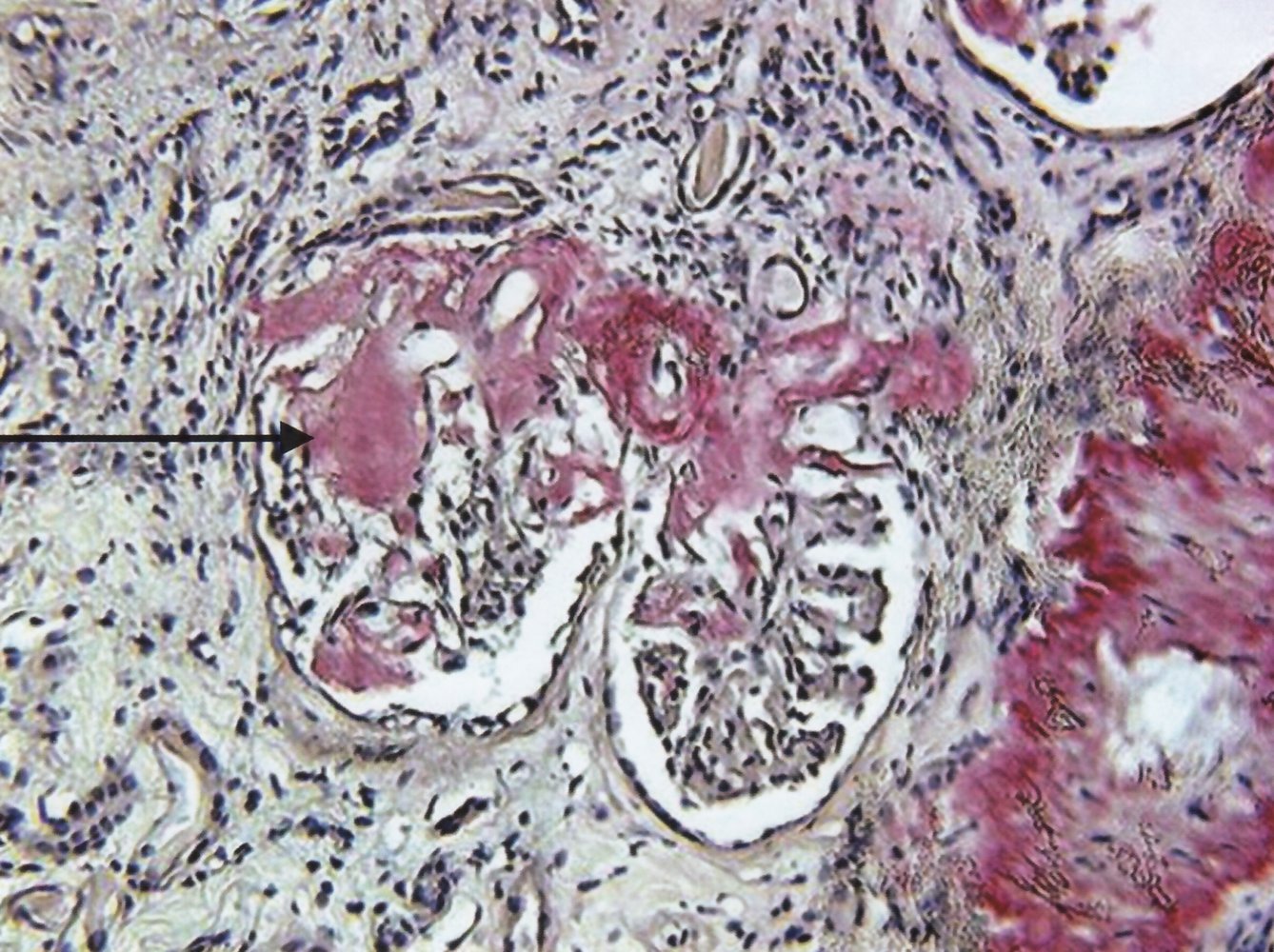

Kidney tissue biopsy; findings include: [15]

- Global and segmental amyloid deposition

- Diffuse and/or focal glomerular involvement

- Enlargement of glomeruli

- Tubular atrophy

- Interstitial fibrosis

- Assessment of organ involvement, including BMP, estimated GFR, urinalysis

- For suspected cardiac involvement: multiparametric CMR (including late-gadolinium-enhancement imaging and novel mapping-based approaches) [16]

-

Kidney tissue biopsy; findings include: [15]

- Identify the underlying inflammatory disorder (if not yet known); consider:

- Chest x-ray

- Inflammatory markers: ESR, CRP

- Genetic testing for familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) [4]

Amyloidosis should always be considered in patients who present with kidney, liver, or GI involvement in the setting of chronic inflammatory and/or infectious disease.

Management [1][4][14]

- Treat the underlying condition to reduce AA production (mainstay of treatment), e.g.:

- Colchicine for FMF [1]

- Antimicrobials for chronic infections (e.g., TB, bronchiectasis)

- DMARDs for rheumatological diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis)

- Consider therapy with IL-1 or IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., anakinra or tocilizumab). [5]

- Provide supportive care for associated complications (e.g., CKD).

Prognosis [1][12]

- Median survival after diagnosis: approx. 11 years [1]

- Survival depends largely on the severity of end-organ damage at diagnosis.

- Approx. 40% of patients will require renal replacement therapy. [12]

Overview [17]

- Mutated transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRmt) is the most common type of hereditary amyloidosis. [1]

- Clinical phenotype (e.g., cardiomyopathy, polyneuropathy, or mixed) is determined by the type of mutation. [1]

| Overview of ATTRmt amyloidosis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical phenotype | Familial amyloid cardiomyopathy (FAC) | Familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) |

| Etiology |

|

|

| Epidemiology |

|

|

| Affected sites |

|

|

Management [4][5]

- Obtain diagnostics of amyloidosis, including tissue biopsy.

- Consider genetic testing to confirm the presence of a mutation.

- Consider pharmacotherapy with TTR stabilizers (e.g., tafamidis ). [3][21]

- Liver transplantation should be considered to decrease the source of amyloid protein . [3][5]

- In localized amyloidosis (e.g., endocrine amyloidosis), a single organ is affected.

- A definitive diagnosis can only be made on histopathology.

- Management is specialist-guided and organ-specific.

| Examples of localized amyloidosis [22][23] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Example diseases | Affected protein | ||||

| Nonneurologic diseases | Isolated atrial amyloidosis (↑ risk of atrial fibrillation) | ANP (physiological in old age) | ||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) deposits in pancreatic islet | |||||

| Injection-localized amyloidosis (from insulin injection in diabetes mellitus) | Amyloid at insulin injection site (AIns) | |||||

| Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid | Calcitonin amyloid (ACal) | |||||

| Neurodegenerative diseases (cerebral amyloidosis) | Alzheimer disease | Aβ (cleaved from the APP) | ||||

| Prion diseases | APrP (prion protein amyloid) | |||||