Introduction

There are 3 major antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides:

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (formerly Wegner granulomatosis).

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) (formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome).

- Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Despite having different clinical presentations, all 3 conditions have the following in common:

- Hyperactivated neutrophils, mediated in part by ANCAs.

- Necrotizing inflammation of small vessels, including arterioles, capillaries, and venules.

- Rapidly progressive organ damage, particularly affecting the kidneys and lungs.

Pathogenesis

ANCA autoantibodies

ANCAs are autoantibodies directed against certain proteins found in neutrophils. The 2 ANCAs of clinical significance are:

- Anti-proteinase-3 (PR3): PR3 is a neutrophil protease located in granules spread diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of neutrophils. Due to PR3's cytoplasmic distribution, anti-PR3 is referred to as c-ANCA.

- Anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO): MPO is a neutrophil oxidative burst enzyme located in granules clustered around the nucleus of the neutrophils. Due to MPO's perinuclear distribution, anti-MPO is referred to as p-ANCA.

The origin of ANCA is unclear. They likely form during neutrophil cell death, which exposes neoepitopes from intracellular proteins such as PR3 and MPO. Episodes of tissue damage associated with extensive neutrophil turnover (eg, prior suppurative infections) probably contribute to ANCA formation in susceptible individuals.

Neutrophil activation

ANCAs themselves are relatively ineffective at activating resting neutrophils directly because PR3 and MPO are inaccessible within intracellular granules. However, neutrophils translocate PR3 and MPO to their surface as they degranulate, such as when primed by an infection (eg, bacterial endotoxin, acute phase cytokines [eg, TNF-α, IL-1β]). The membrane-bound PR3 and MPO can be crosslinked by circulating ANCAs, amplifying the neutrophil activation. This leads to a vicious cycle as ANCA-activated neutrophils continue to present PR3 and MPO on their surfaces.

Vasculitic inflammation

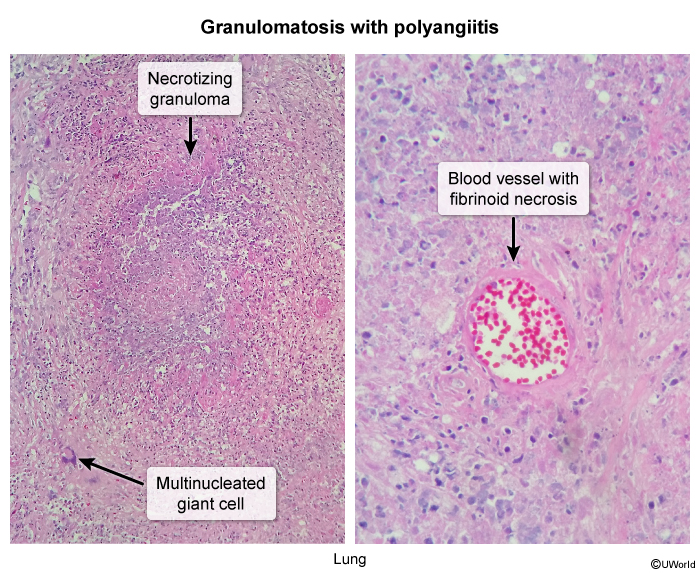

Activated neutrophils cause endothelial damage via respiratory oxidative burst (eg, MPO) and protease activity (eg, PR3). The neutrophils lodge within small vessels such as glomerular tufts and pulmonary capillaries, explaining the prominent involvement of the kidneys and lungs. Histology of GPA reveals fibrinoid necrosis (amorphous debris representing lysis of the media

These necroinflammatory changes can affect multiple vascular beds (ie, polyangiitis). Vessel inflammation disrupts blood flow, causing tissue damage such as necrotizing sinusitis, microscopic lung infarctions (eg, pulmonary nodules and cavities), glomerulonephritis, peripheral nerve ischemia (eg, mononeuritis multiplex), and skin lesions.

Risk factors

Genetic

Genetic risk factors may increase the likelihood of ANCA formation, ANCA-induced neutrophil activation, and clinical vasculitis. They include polymorphisms that:

- Increase PR3 expression (eg, PRTN3 promoter).

- Decrease antiproteases that normally inhibit PR3 (eg, SERPINA1 [alpha-1 antitrypsin]).

- Enhance autoreactive T-cell responses to self-antigens (eg, HLA-DPB1).

Environmental

Environmental risk factors likely influence initial neutrophil activation, presenting an opportunity for amplification by ANCA. They include:

- Inhaled exposures (eg, cigarette smoke, silica).

- Pyogenic infections (especially Staphylococcus aureus).

- Certain drugs and medications (eg, hydralazine, propylthiouracil, levamisole).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)

Clinical presentation

GPA mainly affects older adults. Patients usually have inflammatory constitutional symptoms such as low-grade fever, weight loss, anorexia, malaise, and fatigue. The main organs involved in GPA include the sinuses, respiratory tract, and kidneys

- Sinuses: Otolaryngologic involvement includes necrotizing sinusitis, which can progress to septal perforation and erosion into paranasal structures (eg, auditory canal). Manifestations include sinus pain, congestion, nasal crusting and ulcerations, recurrent infections, purulent discharge, saddle nose deformity (late finding), and inner ear symptoms (eg, hearing loss, vertigo). CT imaging shows opacification and osseous destruction of the sinus wall.

- Lungs: GPA can affect the entire respiratory tract, from the upper airway to the pulmonary parenchyma.

- Airway involvement includes laryngitis, tracheitis, bronchial ulceration, and bronchiectasis. Some patients develop intense granulation tissue followed by scarring (eg, tracheal or bronchial stenosis).

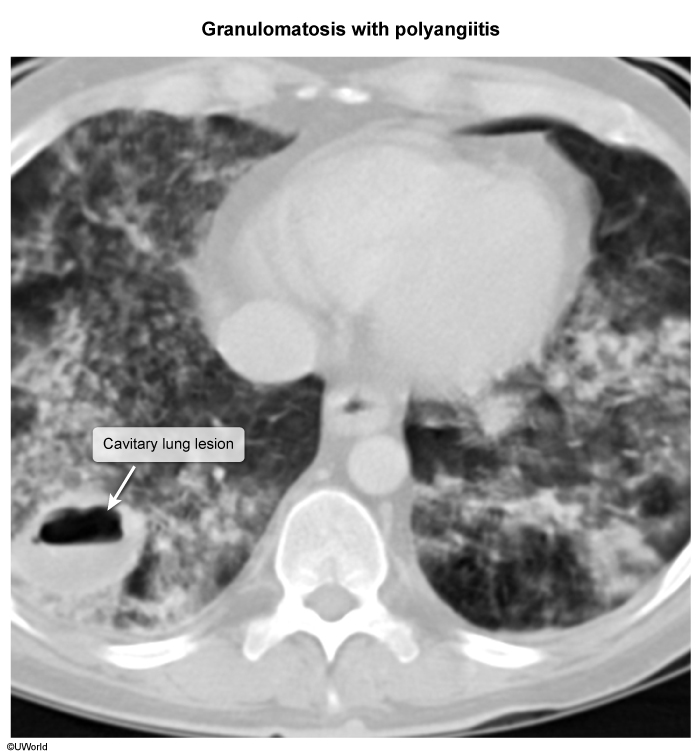

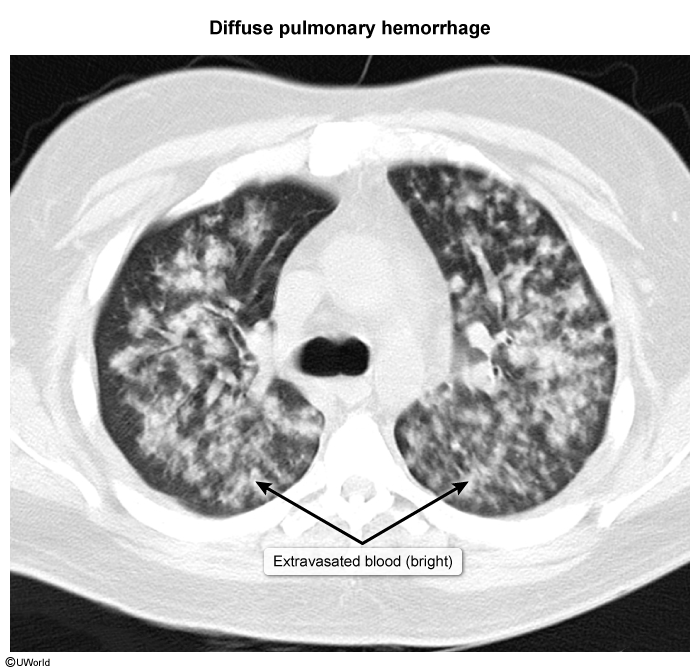

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement includes nodular opacities, consolidations, and cavitary pulmonary infiltrates representing areas of lung inflammation and necrosis ( Widespread capillary inflammation can cause diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), which appears as bilateral alveolar opacification (

image 3Symptoms include chest pain, dyspnea, hypoxemia, and hemoptysis, which can sometimes be life-threatening (eg, erosion into bronchial artery).

image 3Symptoms include chest pain, dyspnea, hypoxemia, and hemoptysis, which can sometimes be life-threatening (eg, erosion into bronchial artery). image 4

image 4

- Kidneys: Renal involvement involves rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), presenting with nephritic syndrome. Manifestations include acute kidney injury, microscopic hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells and red cell casts, hypertension, and edema.

Diagnosis

GPA is most strongly associated with c-ANCA (anti-PR3), present in ~75% of patients.

Diagnosis of GPA requires a tissue biopsy regardless of ANCA serology result (only moderate sensitivity and specificity). Renal biopsy (obtained in all patients with suspected glomerulonephritis) can reveal crescentic lesions composed of sloughed epithelial cells and fibrinous debris within Bowman capsule. Immunofluorescence shows a pauci-immune pattern, referring to the characteristic absence of immunoglobulin or complement deposition. This feature distinguishes GPA from immunologic causes of glomerulonephritis, such as:

- Anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease or Goodpasture syndrome (linear IgG fluorescence).

- IgA nephropathy or Berger disease (granular IgA and C3 fluorescence).

- Immune complex (eg, poststreptococcal) glomerulonephritis (granular IgG and C3 deposits).

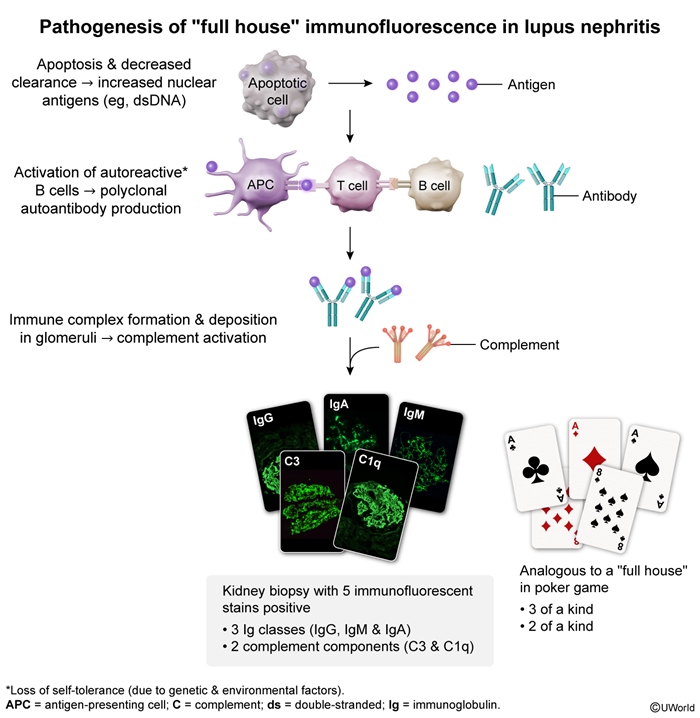

- Lupus nephritis ("full house" staining with IgG, IgA, IgM, and complement (

figure 1

figure 1

Biopsies obtained from extrarenal sites (eg, sinuses, lungs) show small vessel inflammation, fibrinoid necrosis, and perivascular granulomas.

Treatment

Treatment of GPA involves 2 phases:

- Induction: The goal is to achieve initial remission as quickly as possible. Organ-threatening disease (eg, lungs, kidneys, eyes) requires potent immunosuppression, with intravenous corticosteroids (eg, high-dose methylprednisolone) combined with rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that depletes B cells and, subsequently, ANCA autoantibodies). Cyclophosphamide is an alternative to rituximab.

- Maintenance: The goal is to prevent relapse (common) after remission is achieved. Maintenance consists of a single steroid-sparing agent (eg, rituximab, methotrexate, azathioprine). Long-term glucocorticoids are avoided due to their chronic toxicity (eg, osteoporosis).

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)

Clinical presentation

Growing consensus suggests that EGPA has 2 main phases: a nonvasculitic phase and a vasculitic (more severe) phase

- Nonvasculitic: This phase of EGPA, more likely to be ANCA-negative, represents a state of heightened Th2 activation (eg, high IL-5) causing eosinophil proliferation. Most patients have a history of severe asthma beginning in early adulthood, often accompanied by chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Eosinophilia is common, with eosinophils infiltrating various organs (eg, migratory pulmonary opacities).

- Vasculitic: This phase of EGPA (usually >10 years after asthma onset) is more likely to be ANCA-positive. It involves neutrophilic small vessel inflammation, fibrinoid necrosis, and granuloma formation (similar to GPA) but in a background of eosinophilic infiltration. In addition to constitutional symptoms as seen in GPA (eg, fever, weight loss), EGPA typically has the broadest organ system involvement of the ANCA vasculitides. Common extrapulmonary manifestations include:

- Cardiovascular: Myocarditis (leading cause of death) and conduction block.

- Dermatologic: Tender nodules due to subdermal capillary inflammation.

- Neurologic: Mononeuritis multiplex due to vasa nervorum involvement causing inflammation, ischemia, and infarction of large peripheral nerves (eg, foot drop).

- Renal: RPGN (as seen in GPA).

- Gastrointestinal: Bowel ischemia and perforation.

These phases may overlap, with many patients presenting with concurrent asthma (nonvasculitic EGPA) and extrapulmonary manifestations (vasculitic EGPA).

Diagnosis

EGPA is most strongly associated with p-ANCA (anti-MPO), but results are only positive in ~30% of patients, mainly in those with severe multiorgan vasculitis.

Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy demonstrating extravascular eosinophils (with or without necrotizing small vessel vasculitis). Renal biopsy shows pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis, similar to GPA. If biopsy is not possible, a presumptive diagnosis can be made in patients with peripheral blood eosinophilia (≥10% or ≥1,000 cells/mm3) and compatible organ involvement (eg, myocarditis, mononeuritis multiplex, glomerulonephritis).

Treatment

Treatment of EGPA involves 2 phases:

- Induction: The goal is to rapidly achieve initial remission. Organ-threatening disease (eg, heart, kidneys, CNS) is typically seen in vasculitic EGPA, and requires aggressive immunosuppression with intravenous corticosteroids (eg, high-dose methylprednisolone) combined with cyclophosphamide (a cytotoxic drug that blocks multiple immune cells). Rituximab is an alternative to cyclophosphamide but is less effective because most patients are ANCA-negative (ie, lack active secretion by B cells).

- Maintenance: The goal is to prevent relapse following remission. Maintenance consists of a steroid-sparing agent (eg, mepolizumab, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate).

Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 (eg, mepolizumab) or IL-5 receptor (eg, benralizumab) are also used to treat nonvasculitic components such as EGPA-associated asthma. Nonvasculitic EGPA tends to be highly responsive to these biologic agents because they rapidly deplete eosinophils.

Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)

Clinical presentation

MPA has a presentation similar to GPA, with often dramatic renal (eg, RPGN) and pulmonary (eg, extensive cavitary lesions, DAH) involvement. Upper airway and sinus disease is less pronounced.

Diagnosis

MPA is most strongly associated with p-ANCA (ie, MPO).

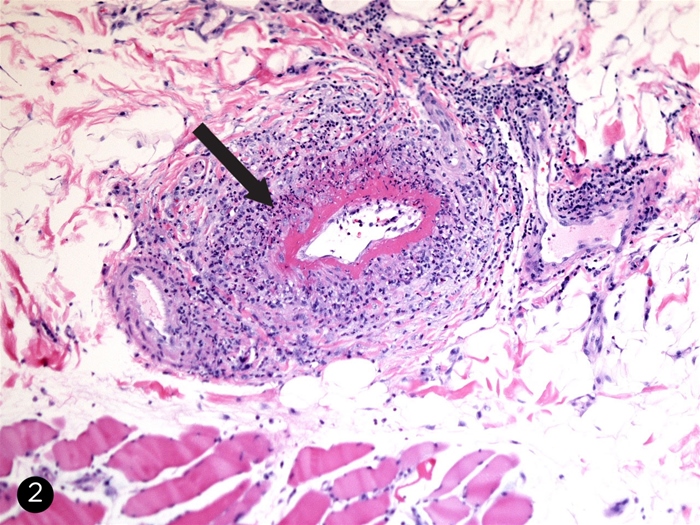

Similar to GPA, MPA requires a tissue biopsy for diagnosis. Renal biopsy shows pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis indistinguishable from GPA or EGPA. Extrarenal biopsy shows fibrinoid necrosis and intense neutrophilic inflammation but a lack of granulomas around small vessels. Unlike GPA and EGPA, MPA appears to have minimal T-cell autoreactivity, which is needed for type IV hypersensitivity and granuloma formation.

Treatment

Treatment of MPA is analogous to GPA, with combination induction therapy (eg, systemic glucocorticoids plus rituximab or cyclophosphamide) followed by maintenance therapy with a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive drug. Due to the lack of a strong autoreactive T-cell (granuloma-inducing) component, MPA has a much lower risk of relapse than GPA or EGPA, so immunosuppression can be tapered off sooner.

Other variants

Drug-induced ANCA vasculitis

Certain drugs can produce ANCA-positive small vessel vasculitis; the top culprits are propylthiouracil, hydralazine, minocycline, and levamisole. These can induce ANCA formation through different mechanisms:

- Propylthiouracil is an antithyroid medication that interferes with thyroid peroxidase; it can cross-react with neutrophil NPO, altering its structure to render it more immunogenic.

- Hydralazine is an antihypertensive medication that causes oxidative stress within neutrophils, leading to apoptosis and exposure of neoepitopes such as PR3.

- Levamisole is a (largely obsolete) antihelminthic drug used to adulterate or "cut" cocaine; it has broad immunostimulatory activity, including T-cell activation and neutrophil activation.

Drug-induced ANCA vasculitis is suspected in patients with a clinical picture of c-ANCA vasculitis (ie, GPA) but with an unexpected ANCA pattern such as p-ANCA or double positivity for p-ANCA and c-ANCA. Double ANCA positivity is highly suspicious for levamisole vasculitis in patients with glomerulonephritis and/or diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

Renal-limited vasculitis

A small subset of individuals have isolated pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. ANCA-associated vasculitis might not be initially suspected due to the lack of additional organ involvement such as pulmonary lesions or sinus disease. This renal-limited vasculitis is usually associated with p-ANCA (anti-MPO); it is thought to be a variant of MPA and treated accordingly.

Summary

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis

encompasses 3 major diseases: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). These conditions share a common pathogenesis involving hyperactivated neutrophils causing necrotizing inflammation of small vessels, with prominent involvement of the kidneys and lungs.- GPA is most closely associated with c-ANCA against proteinase-3 (PR3). It presents with destructive sinusitis, pulmonary nodules or cavities, and glomerulonephritis.

- EGPA is most closely associated with p-ANCA against myeloperoxidase (MPO). It presents with asthma, chronic sinusitis, eosinophilia, and more severe vasculitic features such as glomerulonephritis, myocarditis, and mononeuritis multiplex.

- MPA is most closely associated with p-ANCA. It presents with dramatic renal and pulmonary manifestations (eg, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage).

Diagnosis generally requires tissue biopsy when possible. Renal biopsy demonstrates pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Treatment combines systemic glucocorticoids with additional immunosuppressive agents such as rituximab or cyclophosphamide. Long-term immunosuppression is usually necessary because relapse is common.