Aspergillosis is a fungal infection caused by the Aspergillus species. The most common clinical manifestations are allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), and invasive aspergillosis. ABPA is a respiratory hypersensitivity reaction caused by exposure to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens and typically affects individuals with underlying asthma or cystic fibrosis. Clinical features of ABPA include wheezing, cough, and expectoration of brown mucus plugs. CPA is a spectrum of chronic lung infections caused by Aspergillus spp. (ranging from a single aspergilloma to chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis) that occur in individuals with preexisting lung diseases such as tuberculosis or COPD. Symptoms of CPA include chronic cough, fatigue, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Invasive aspergillosis is a severe infection characterized by invasion of lung tissue by Aspergillus spp., which results in severe pneumonia with potential dissemination to other organs. This condition primarily affects immunocompromised individuals, including those undergoing chemotherapy or stem cell or organ transplant. Clinical features vary based on organ involvement and include fever, cough, and dyspnea. Diagnosis of aspergillosis varies based on clinical manifestation and typically involves a combination of imaging, culture, and/or serology. Treatment may include systemic glucocorticoids to reduce inflammation, antifungal therapy (e.g., itraconazole or voriconazole), and/or surgical resection, depending on the clinical presentation.

Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis is described in a separate article. See “Sinusitis.”

-

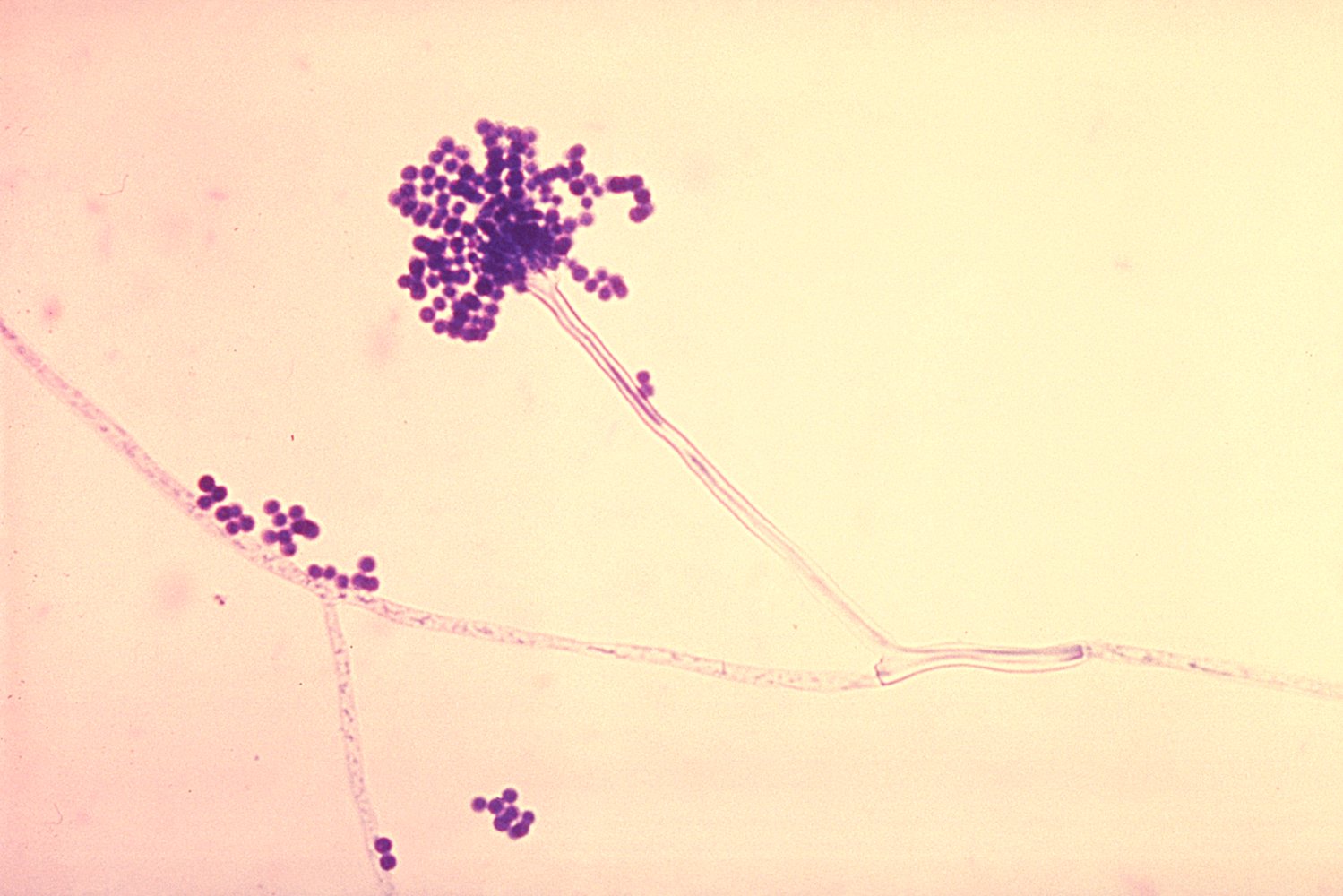

Pathogen

- Aspergillus, a genus including over 200 species

- Most common: Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus

-

Transmission: airborne exposure to mold spores

- Aspergillus spores (also referred to as conidia) are ubiquitous indoors, as they enter with the normal flow of air.

- The spores can also settle on easily accessible sources of nutrition (e.g., water), dust, cellulose (e.g., in wallpaper), and indoor plants

- Aspergillus spores may also be found in intensive care units

ABPA is a respiratory hypersensitivity reaction caused by exposure to A. fumigatus antigens. [1]

Risk factors [2]

- Preexisting bronchopulmonary conditions (e.g., asthma, cystic fibrosis) [1]

- Genetic factors

Clinical features [2][3]

- Persistent asthma symptoms and acute asthma exacerbations despite adherence to appropriate asthma treatment

- Productive cough with brown mucus plugs, hemoptysis

- Low-grade fever, fatigue, malaise, weight loss

- Clinical features of sinusitis in patients with concurrent allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (see “Fungal rhinosinusitis”)

Diagnostics

Suspect ABPA in individuals with asthma or cystic fibrosis (CF) who have refractory respiratory symptoms.

Laboratory studies [2][3][4]

- A. fumigatus sensitization: ↑ A. fumigatus IgE levels (e.g., ≥ 0.35 kUA/L) [2]

- Supportive findings

- ↑ Total IgE levels (e.g., ≥ 500 IU/mL) [2]

- ↑ A. fumigatus IgG levels

- Eosinophilia (> 500 cells/mcL) [2]

- Positive in vivo allergy skin tests to Aspergillus [3][4]

Increased IgE and eosinophil count are common findings in ABPA.

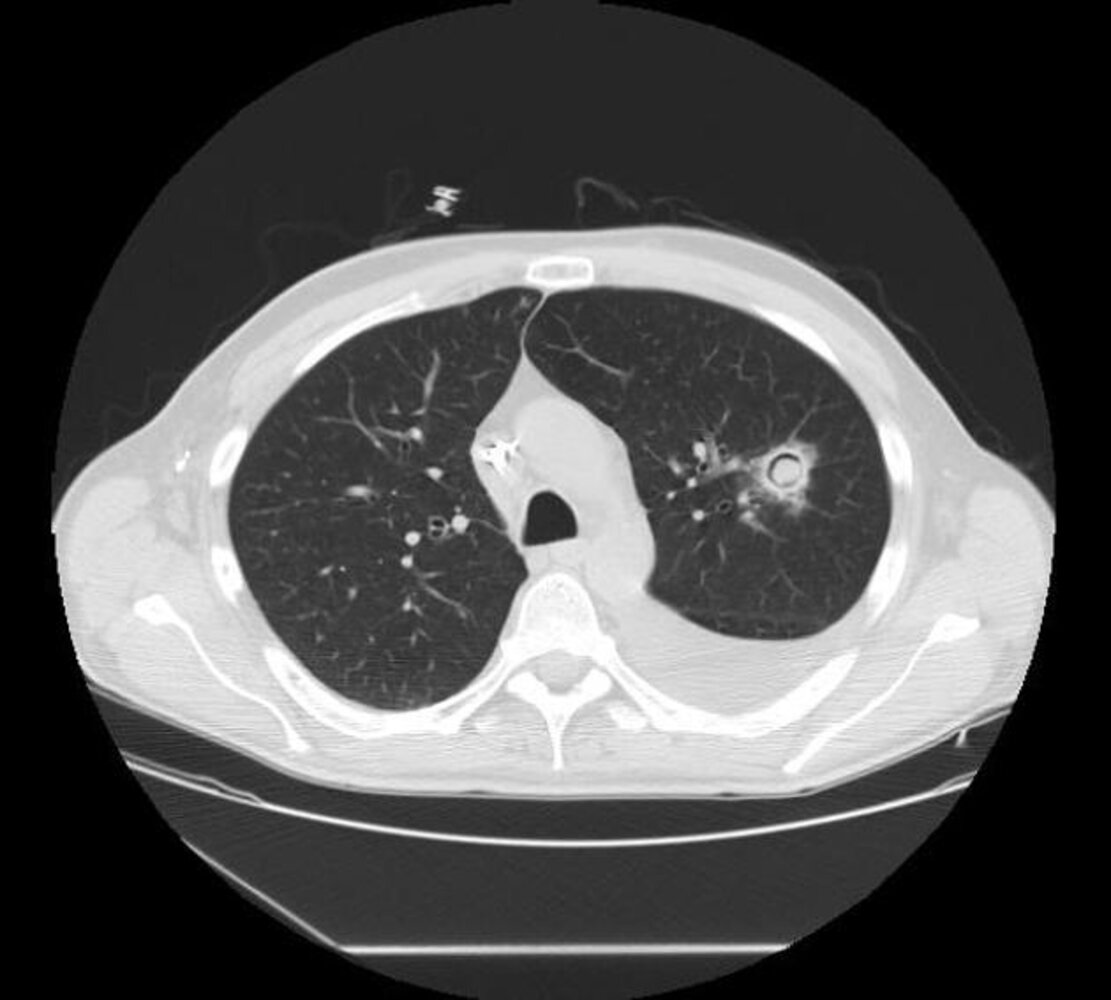

Imaging [2][3]

- Obtain HRCT chest in all patients with suspected ABPA.

- Typical findings include:

- Central bronchiectasis

- Pulmonary infiltrates

- Mucoid impaction

- Mosaic attenuation

- Tree-in-bud sign

- Fibrosis

- Centrilobular nodules

Management [2][4][5]

Promptly treat ABPA by decreasing the immune response through management and prevention of acute exacerbations and decreasing the fungal burden with antifungals. Consult pulmonology and/or infectious diseases for help with management.

- Oral glucocorticoids: e.g., prednisone to reduce the inflammatory response [6]

-

Antifungal therapy: to reduce the fungal burden [4]

- Preferred: itraconazole [4]

- Alternatives include voriconazole (off-label) [4]

- Surgical debridement: for select patients with allergic fungal rhinosinusitis

-

Prevention of acute exacerbations

- Avoidance of Aspergillus exposure (see “Prevention”)

- Age-appropriate vaccinations (e.g., pneumococcal vaccine, Hib vaccine)

- Treatment of underlying conditions: e.g., asthma, CF

- Monitoring: Follow up at least every 8 weeks to monitor improvement in symptoms, total IgE levels, and radiographic findings. [2]

Delaying treatment of ABPA can lead to pulmonary fibrosis, chronic bronchiectasis, and permanent loss of lung function. [5]

CPA is a spectrum of chronic lung infections caused by Aspergillus spp. in individuals with preexisting lung disease.

Risk factors [7]

-

Destructive pulmonary pathology, e.g.:

- Scar tissue or lung cavities (e.g., from tuberculosis)

- Sarcoidosis

- Pneumocystis pneumonia

- COPD, emphysema

- Subacute invasive aspergillosis is associated with moderate immunosuppression, e.g., alcohol use disorder, prolonged glucocorticoid use, COPD, malnutrition, and type 2diabetes. [7]

Clinical features [3][7][8]

- Occasionally asymptomatic (may be an incidental finding on chest imaging)

- Chronic productive cough

- Hemoptysis

- Shortness of breath

- Fever, weight loss, night sweats

- Chronic fatigue

- Signs of an underlying lung pathology (e.g., digital clubbing in tuberculosis)

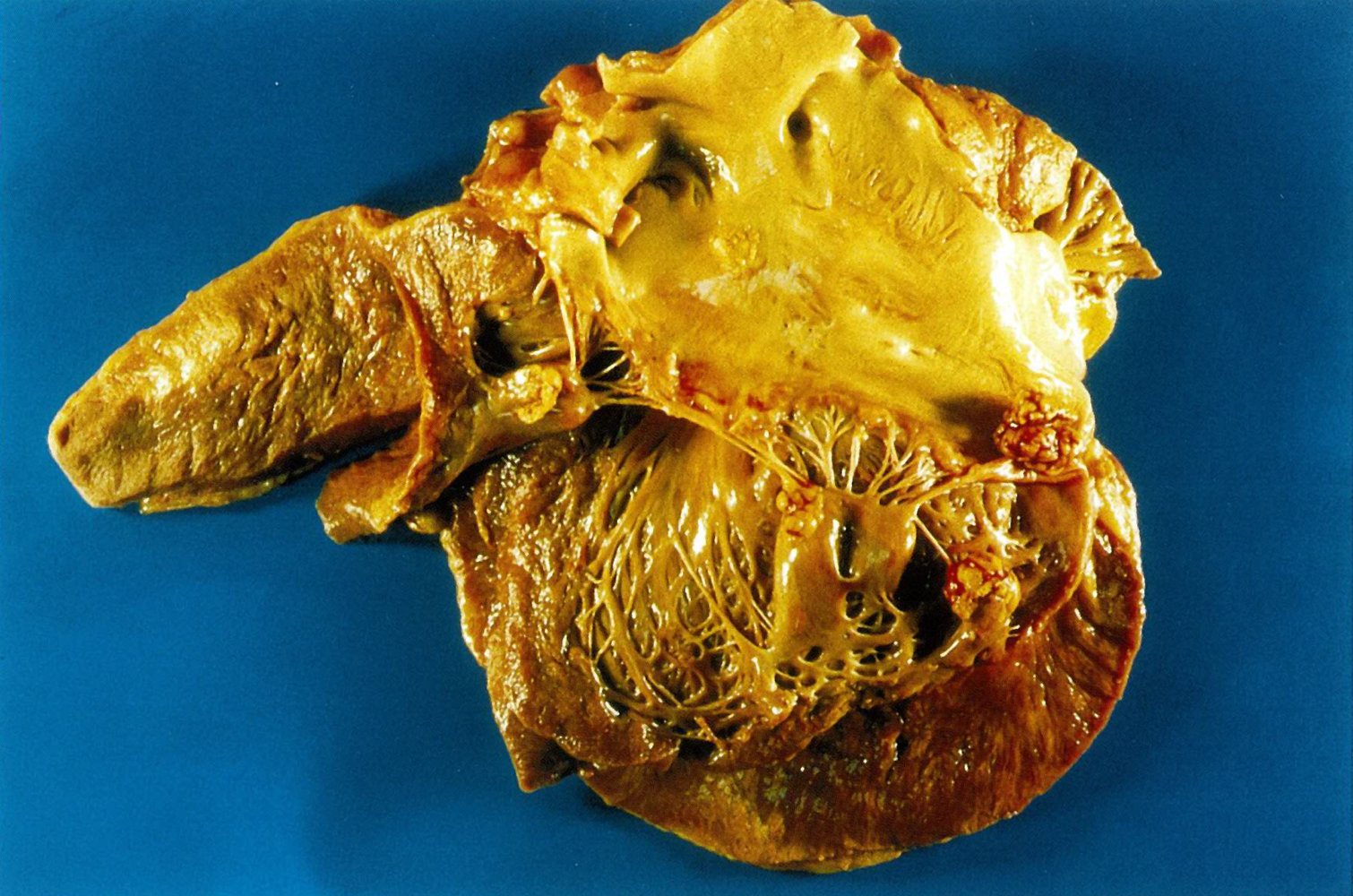

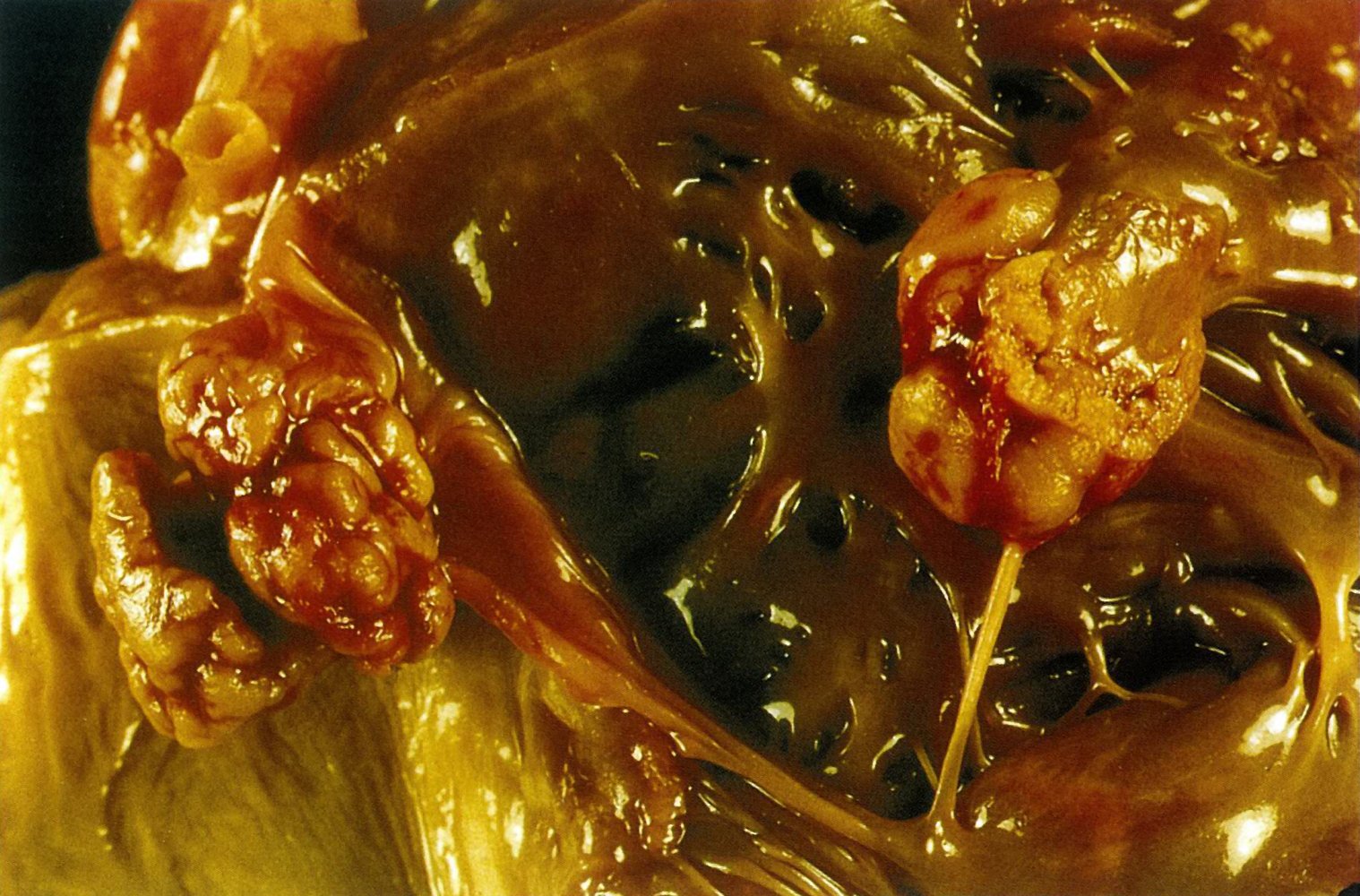

Manifestations [7][8]

- Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (most common): one or more pulmonary cavities containing aspergillomas and/or microbiological or serological evidence of Aspergillus spp. along with pulmonary and/or systemic symptoms

- Aspergilloma: an Aspergillus fungus ball in a preexisting pulmonary cavitary lesion (e.g., from tuberculosis)

- Aspergillus nodule: one or more nodules with possible cavitation and necrosis

- Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis: severe fibrotic destruction of ≥ 2 lung lobes due to untreated chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis [7]

- Subacute invasive aspergillosis (formerly chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis): a type of aspergillosis characterized by pulmonary cavitation, nodules, and consolidations that progress over 1–3 months [7]

Diagnostics

Laboratory studies [7]

Test for direct evidence of Aspergillus infection in patients with characteristic clinical or radiographic features for ≥ 3 months. [7]

-

Positive Aspergillus IgG serology confirms the diagnosis in patients with:

- Radiographic evidence of an aspergilloma

- Other radiographic evidence of CPA after differential diagnoses have been excluded

- If serology is negative, consider other modalities to identify an immunologic response to Aspergillus spp., e.g.:

- Serum Aspergillus antibody levels

- Galactomannan enzyme immunoassay or Aspergillus DNA testing of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- Fungal hyphae or Aspergillus spp. from biopsy and/or respiratory fluids (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage, sputum)

Serum galactomannan enzyme immunoassay has low sensitivity and should not be used to diagnose CPA. [7]

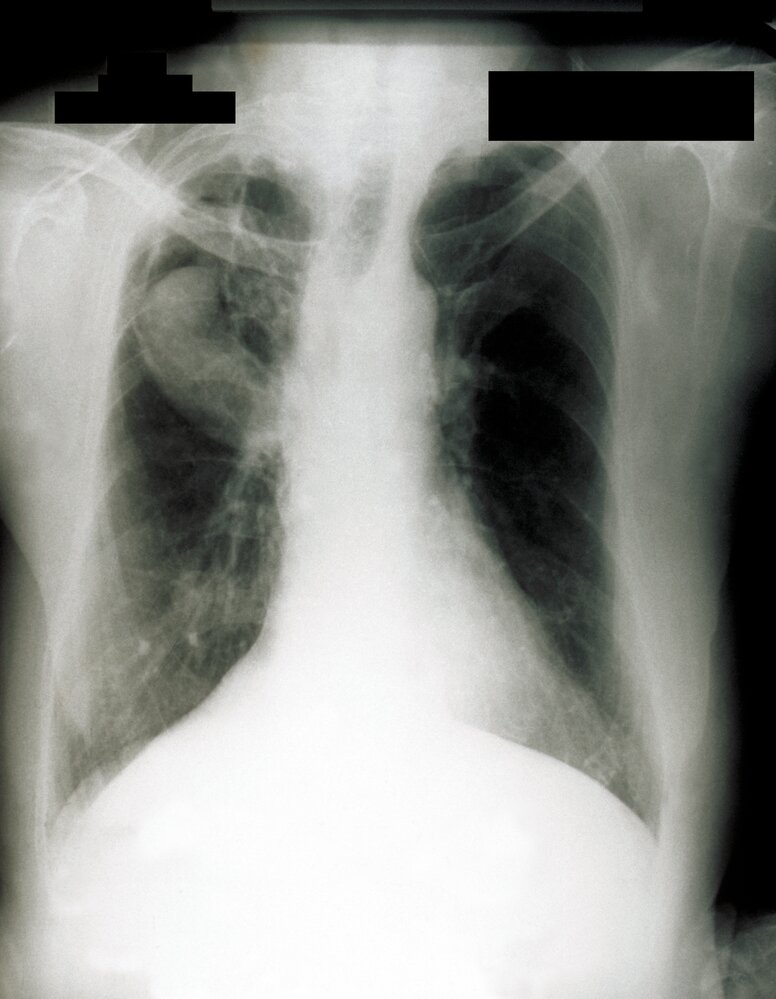

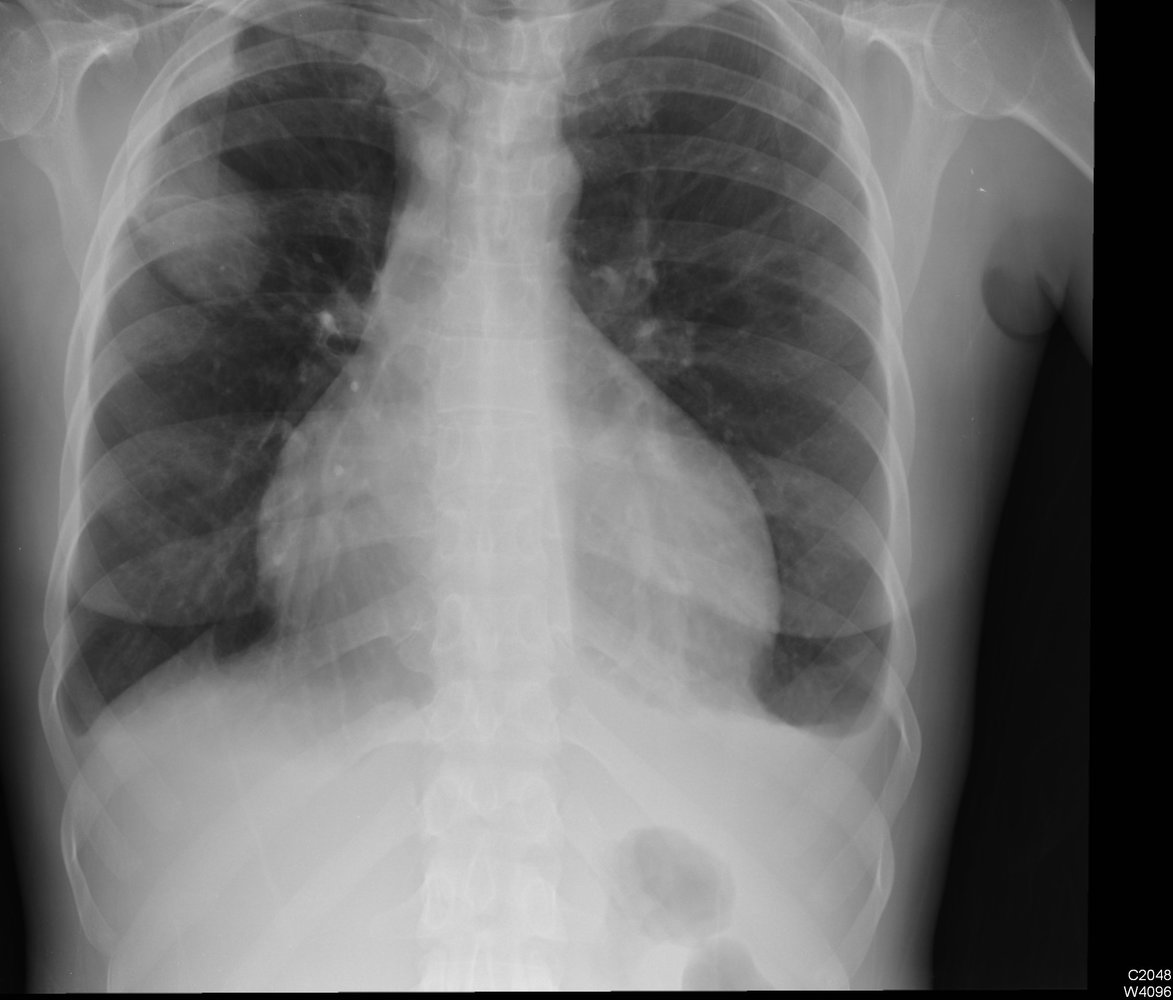

Chest imaging [7][8]

- Chest x-ray (initial test)

- CTA of the thorax if there are findings of CPA on chest x-ray

- Findings include:

- Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis: one or more cavities, often with irregular intraluminal material and/or aspergilloma, pericavitary infiltrates, and/or pleural thickening [4]

-

Aspergilloma

- Mobile fungus ball (visible when the patient is moved from a supine position to a prone or lateralrecumbent position)

- Monod sign: a peripheral air crescent surrounding a fungus ball in a preexisting lung cavity

- The upper lobe is most commonly affected

- Aspergillus nodule: one or more nodules (may be cavitated), frequently necrotic

- Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis: cavities and extensive fibrosis

- Subacute invasive aspergillosis: cavities, nodules, and/or consolidations with abscess formation

Differential diagnosis of CPA

- Mycobacterial infections (e.g., TB, nontuberculous mycobacteria)

- Lung cancer

- Pulmonary infarction

- Vasculitides

- Rheumatoid nodules

- See also “Differential diagnoses of pulmonary fungal infections.”

Management [4]

- Expectant management: for asymptomatic patients without disease progression, e.g., those with incidentally discovered Aspergillus nodules [4][9]

-

Systemic antifungal therapy [4]

- Indications: symptomatic patients and/or those with radiographic progression or loss of lung function.

- Duration: Usually at least 6 months

- Preferred agents: itraconazole or voriconazole (off-label) [4][8][9]

- Alternative agent: posaconazole

-

Surgical resection

- Indicated for symptomatic patients with an aspergilloma [4]

- Considered in patients with:

- Symptomatic disease refractory to antifungal therapy [4]

- Refractory hemoptysis [8]

- Management of hemoptysis: e.g., bronchial artery embolization, oral tranexamic acid, surgical resection [8]

Voriconazole may be more effective in subacute invasive aspergillosis. [4][9]

Invasive aspergillosis is a severe form of Aspergillus infection resulting from the invasion of lung tissue by Aspergillus species, which results in severe pneumonia with potential dissemination to other organs. [8]

Risk factors [4][8][9]

-

Immune deficiency

- Prolonged neutropenia or neutrophil dysfunction (e.g., due to chronic granulomatous disease)

- Immunosuppression (e.g., due to AIDS, chemotherapy, after solid organ or stem cell transplant)

- Hematologic malignancy (e.g., acute leukemia)

- Glucocorticoid use

- Critical illness

- Other chronic diseases, e.g.:

- COPD

- HIV

- Liver disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Extensive exposure to Aspergillus spores in hosts

Clinical features [8]

Symptoms are most commonly caused by pulmonary involvement. Other organ systems can be affected via hematogenous spread (most common in immunocompromised individuals) or direct inoculation (e.g., due to trauma, surgery, foreign bodies). [8]

- Onset [9]

- Days to weeks in patients with prolonged neutropenia

- Weeks to months in patients with additional immune deficiency

- Features of severe pneumonia, e.g.:

- Cough

- Dyspnea

- Tachypnea, tachycardia, hypoxemia

- Fever

- Hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, septic shock following angioinvasion

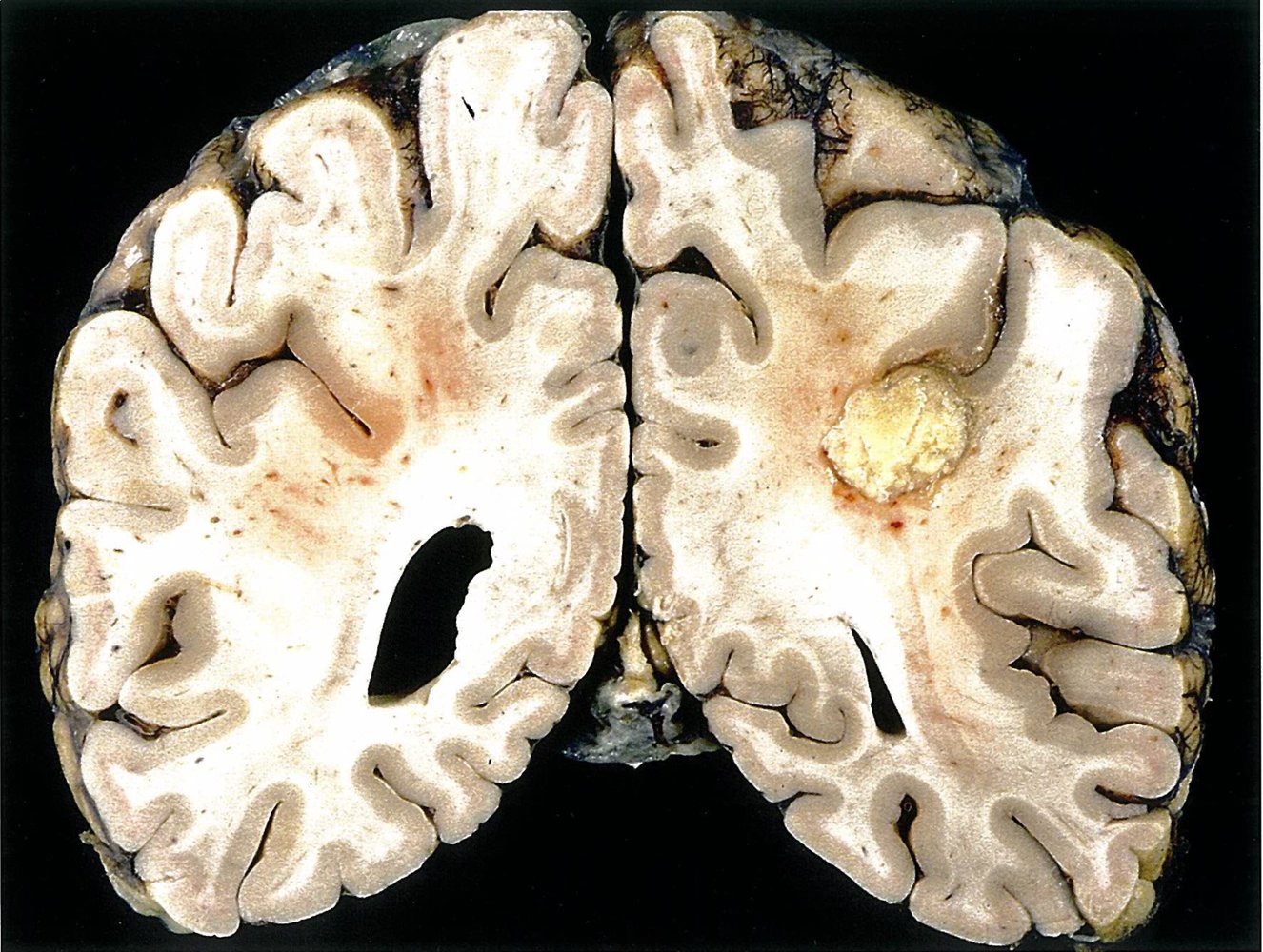

- Features of CNS infection

- Symptoms include headaches, lethargy, altered mental status, seizures, focal neurological deficits. [10]

- Manifestations include brain abscess, meningitis, ventriculitis, and/or cerebral venous thrombosis.

- Features of cutaneous infection [11]

- Induration and erythema

- Macules, nodules, papules, and plaques

- May develop into hemorrhagic bullae or ulcerative nodules and eventually eschars

- Clinical features of infective endocarditis in Aspergillus endocarditis

- Clinical features of sinusitis in Aspergillus sinusitis; may involve invasion of the surrounding tissue

- Features of orbital invasion, e.g., endophthalmitis, decreased visual acuity, painful exophthalmos, or chemosis [12][13]

- Clinical features of UTI, e.g., fever, flank pain [14]

- Clinical features of liver infection, e.g., right upper quadrant pain in liver abscess [15]

Invasive aspergillosis primarily affects the lungs but can also manifest as a disseminated infection (e.g., involvement of skin, CNS).

Diagnostics [8]

Suspect invasive aspergillosis in patients with characteristic clinical features. If laboratory and imaging studies support the diagnosis, confirm with a positive culture or biopsy showing septate hyphae and tissue destruction.

Laboratory studies [4][8]

- Supportive findings include:

- Positive galactomannan enzyme immunoassay: an EIA that detects galactomannan antigen, a heteropolysaccharide component of the Aspergillus cell wall that is shed during hyphal growth

- Positive 1,3-β-D glucan assay [4]

Imaging

Characteristic radiographic findings of Aspergillus infection support the diagnosis.

-

HRCT chest without contrast (for all suspected cases): [3][8]

- Air crescent sign: a radiolucent crescent around a radiopaque nodule, characteristic of invasive aspergillosis

- Halo sign: hemorrhagic ground glass opacities around nodules

- Multiple nodules

- CT and MRI brain with contrast (for suspected CNS Aspergillus infection): [10]

- Ring-enhancing lesions consistent with abscess formation

- Enhancement of intracranial dura

- Bone erosion in Aspergillus sinusitis with invasion of the surrounding tissue

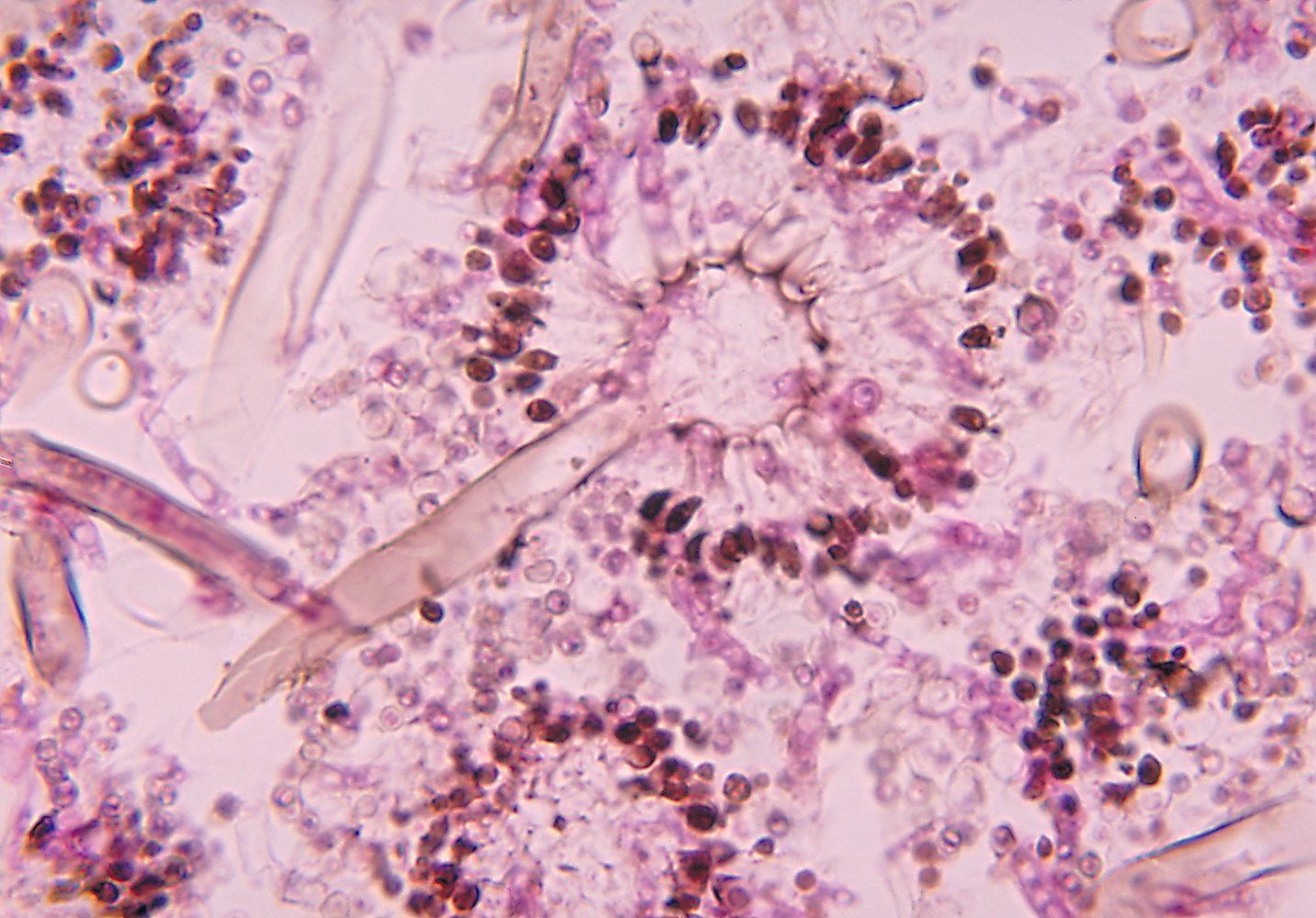

Diagnostic confirmation [4]

- Obtain a tissue or fluid sample (e.g., via bronchoscopy with biopsy and/or bronchoalveolar lavage) if invasive aspergillosis is supported by laboratory and imaging findings. [8]

- Send samples for culture and cytology.

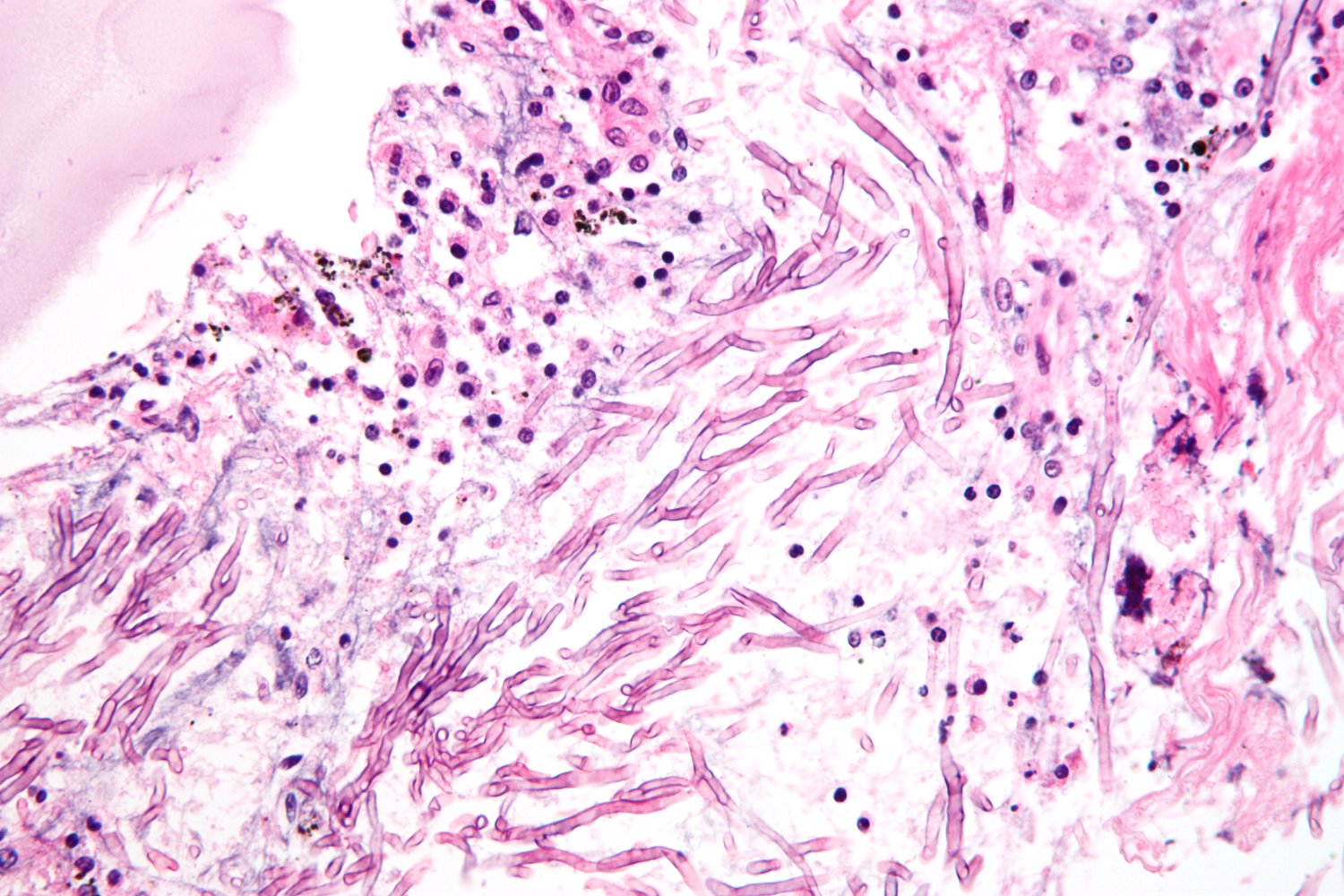

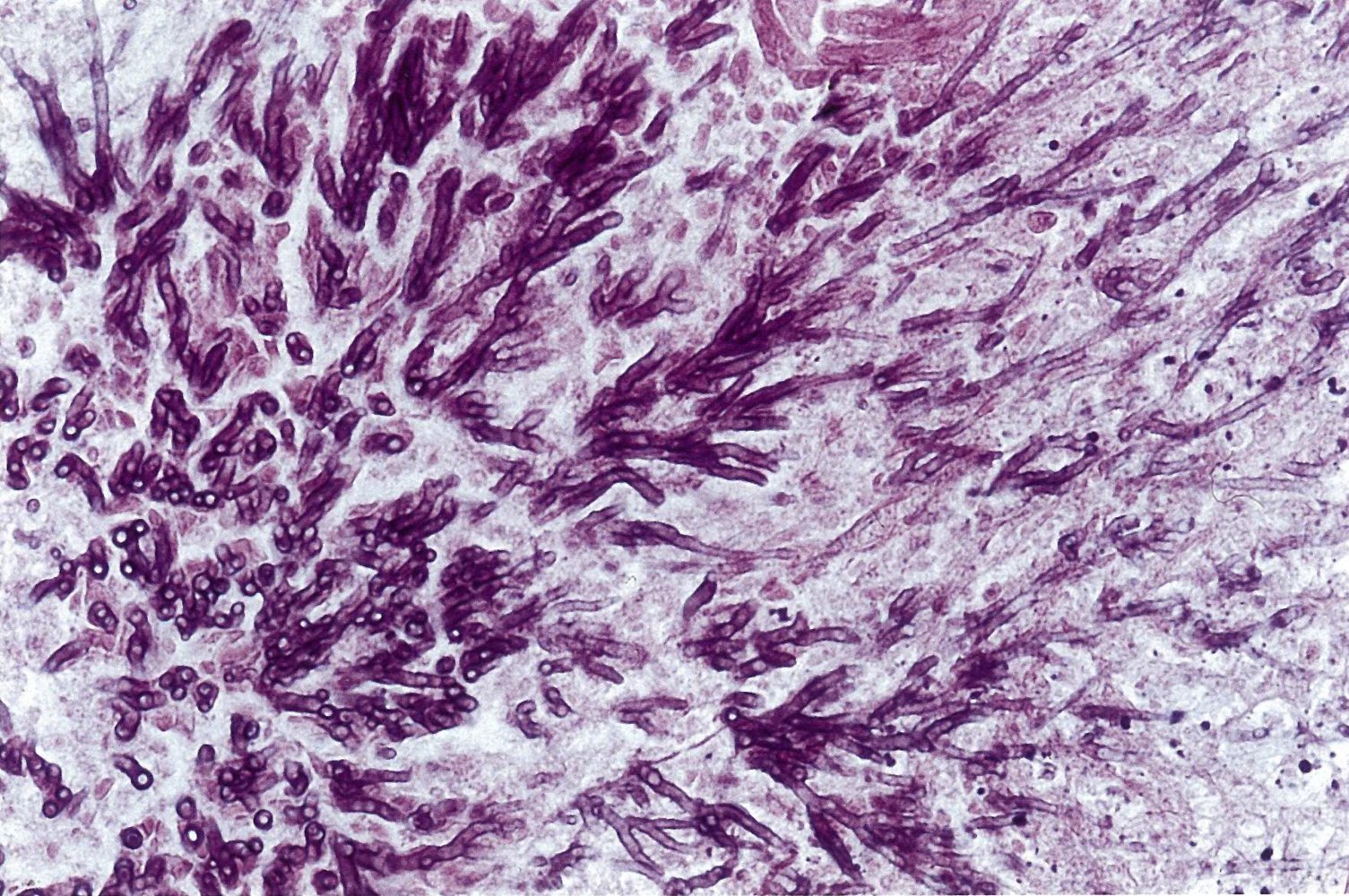

- Staining: Gomori methenamine silver stain or periodic acid-Schiff stain

- Findings: monomorphic and/or septate hyphae branchingdichotomously at 45°

Positive culture or biopsy showing septate hyphae is the gold standard for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis.

Management [3][4][8]

- Consult infectious diseases in all cases of invasive aspergillosis.

- Initiate antifungal treatment promptly.

- Preferred: voriconazole [4]

- Alternatives include:

- Liposomal amphotericin B

- Isavuconazole

- In combination with caspofungin if monotherapy fails

- Manage immunocompromising conditions.

- Initiate antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV.

- Decrease the level of immunosuppression in patients taking immunosuppressants.

- Order additional testing (e.g., echocardiogram, ophthalmologic exam) based on clinical manifestations.

- Encourage protective measures (see “Prevention”).

| Differential diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoses | Etiology | Clinical features | Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Aspergillosis |

|

|

|

|

| Coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) |

|

|

|

|

| Paracoccidioidomycosis |

|

|

|

|

| Blastomycosis |

|

|

|

|

| Histoplasmosis |

|

|

|

|

| Cryptococcosis |

|

|

|

|

| Candidiasis |

|

|

|

|

| Pneumocystis pneumonia |

|

|

|

|

The differential diagnoses listed here are not exhaustive.

Prophylactic therapy [4]

- Indication: severely immunocompromised patients

- Preferred: posaconazole (PO or IV loading dose followed by oral maintenance therapy)

- Alternatives: voriconazole, itraconazole, micafungin, caspofungin

Reduction of mold exposure

The following measures reduce the risk of indoor mold exposure according to the CDC guidelines:

- Protective measures taken at home:

- Use a ventilation hood while cooking

- Add mold inhibitors to wall paint

- Use mold killers in bathrooms

- Ensure regular ventilation (complete opening of the windows for 5–10 min) and adequate heating (especially in winter) in order to keep the humidity as low as possible.

- Avoid drying laundry indoors, use of humidifiers, and carpets in bathrooms.

- Protective measures taken during the construction of buildings, both indoors and outdoors:

- Adequate insulation

- Sealing of the floor to prevent moisture from the soil from entering and pervading it

- Protection from driving rain

- Regular re-roofing

- Ensuring the floors and roofs are watertight.

- Adequate dust cover measures need to be incorporated during construction and restoration work so that there is reduced exposure to the mold present in the dust that is normally stirred up.