Cranial nerve palsy is characterized by a decreased or complete loss of function of one or more cranial nerves. Cranial nerve palsies can be congenital or acquired. Multiple cranial neuropathies are commonly caused by tumors, trauma, ischemia, or infections. While diagnosis can usually be made based on clinical features, further investigation is often warranted to determine the specific cause. Contrast-enhanced MRI is usually the preferred imaging modality to evaluate the affected nerve and any soft tissue abnormalities. A CT scan may be indicated to evaluate for bony lesions and fractures that may be compressing the nerve. Management is mainly aimed at treating the underlying cause. Surgery may be indicated for individuals with severe disability (e.g., acute traumatic cranial nerve palsies, persistent symptoms despite conservative measures). Spontaneous resolution over months may occur, especially in cranial nerve palsies secondary to microangiopathy.

Facial nerve palsy is covered in detail separately.

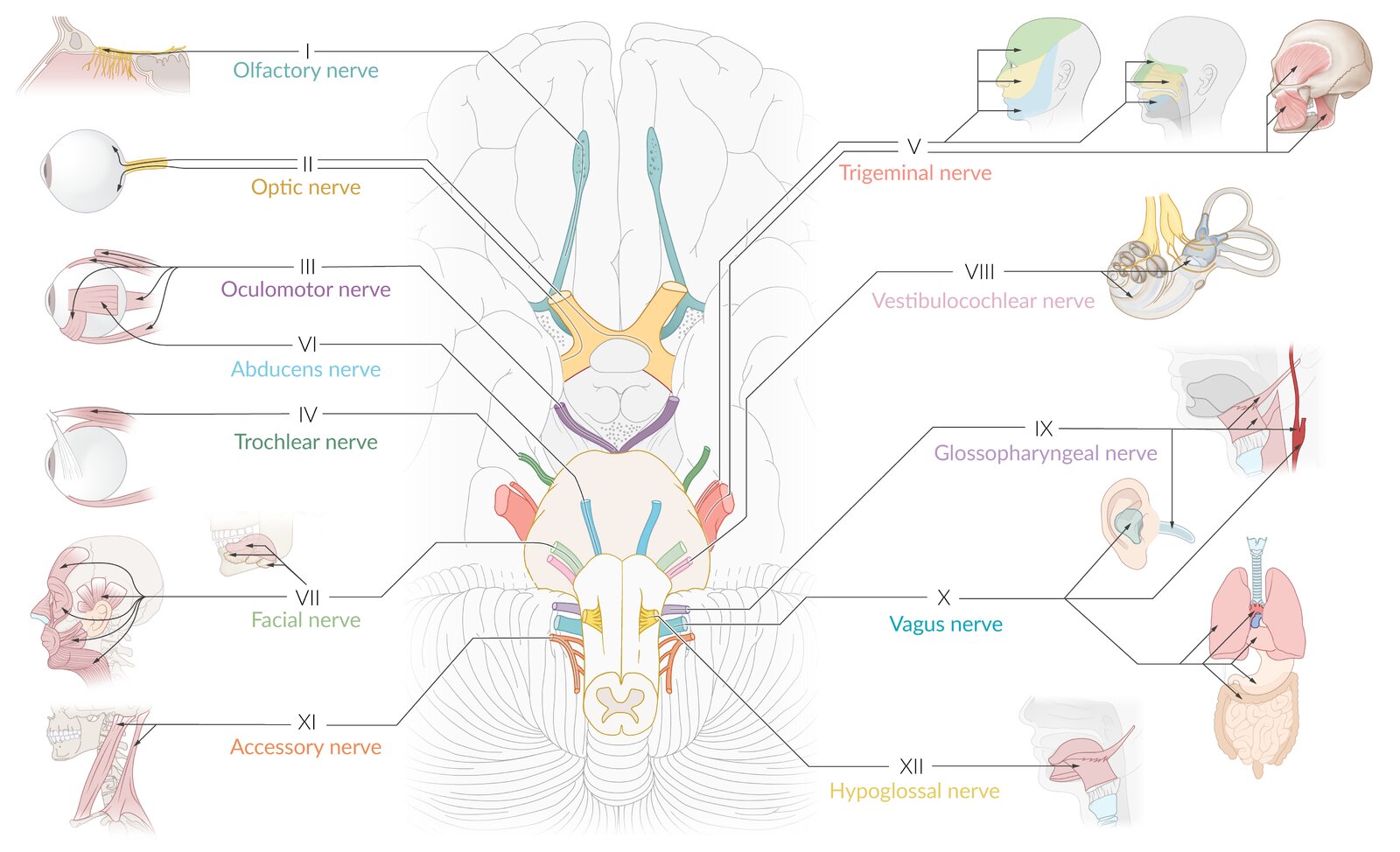

| Overview of cranial nerves and their function [1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cranial nerve | Nerve type | Function | |

| I | Olfactory nerve |

|

|

| II | Optic nerve |

|

|

| III | Oculomotor nerve |

|

|

|

|

||

| IV | Trochlear nerve |

|

|

| V | Trigeminal nerve |

|

|

|

|

||

| VI | Abducens nerve |

|

|

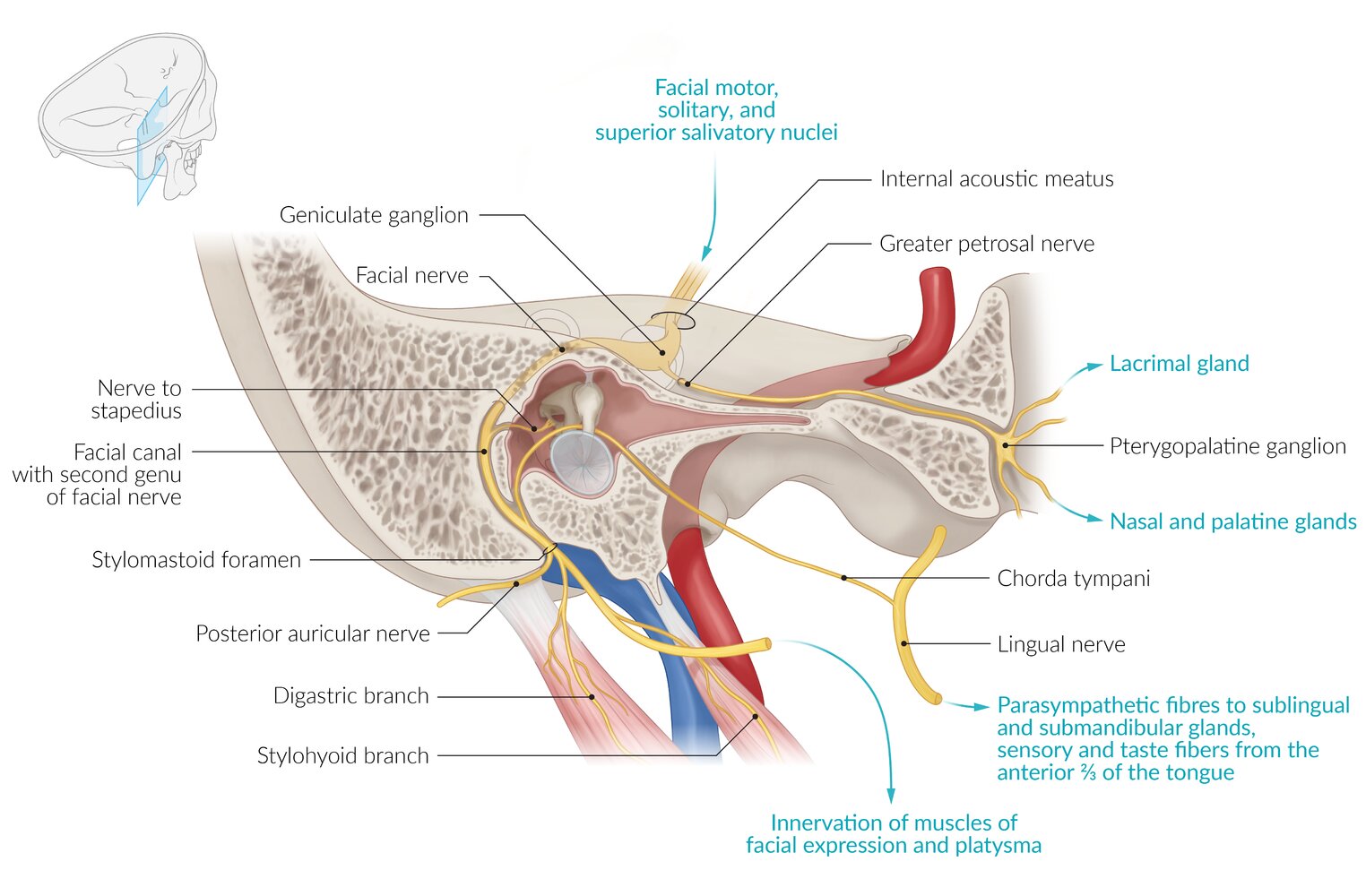

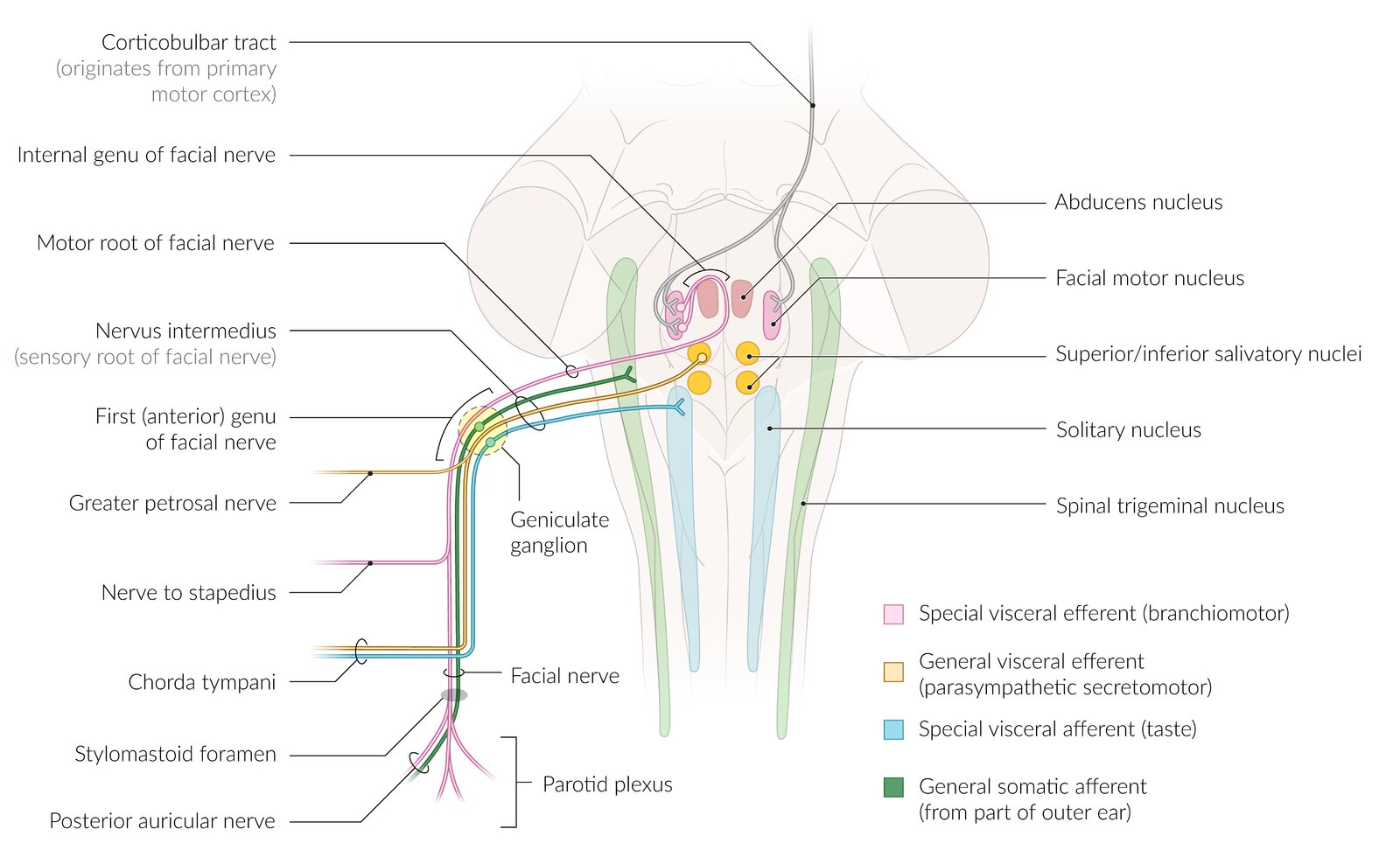

| VII | Facial nerve |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| VIII | Vestibulocochlear nerve |

|

|

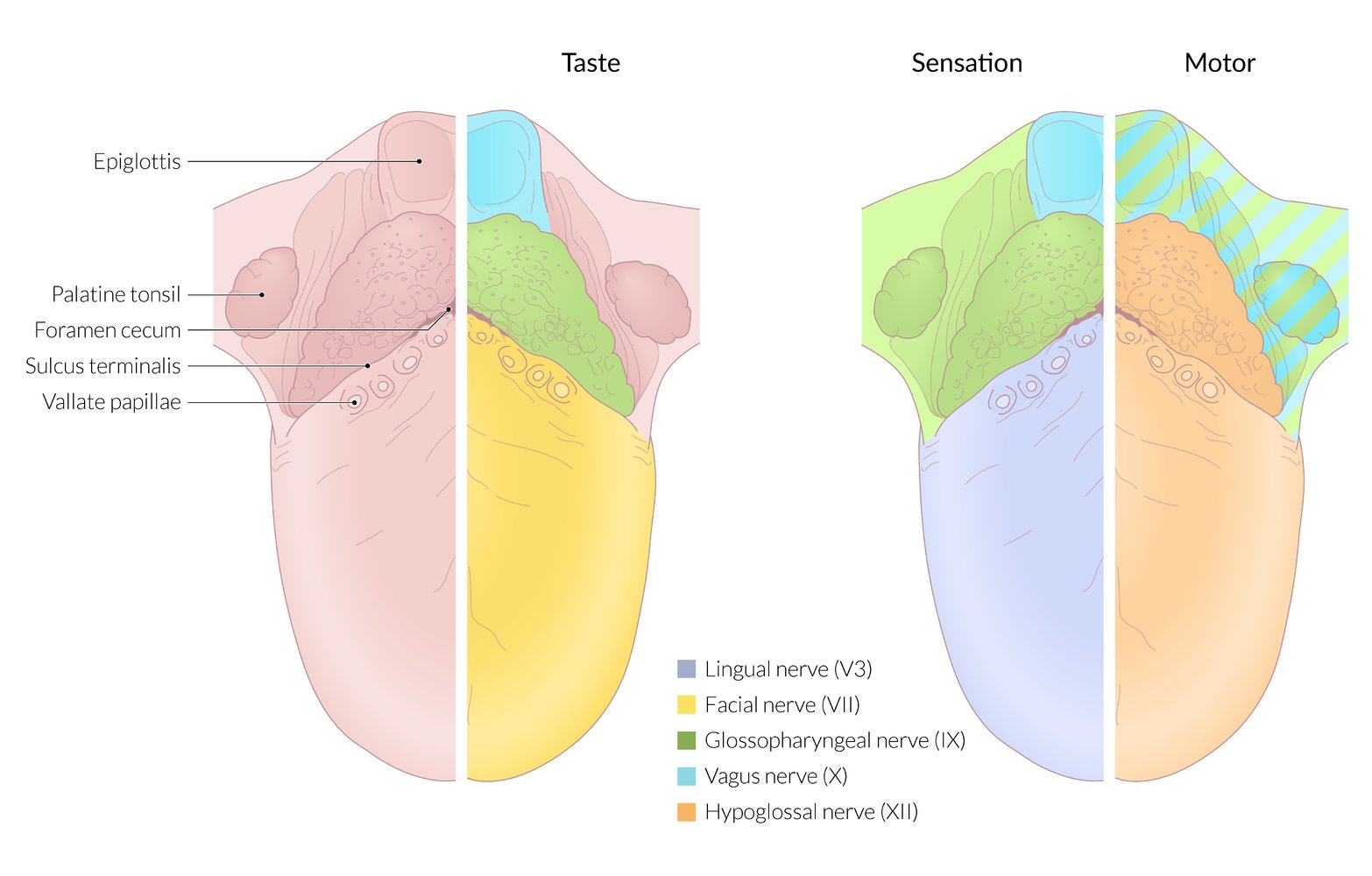

| IX | Glossopharyngeal nerve |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| X | Vagus nerve |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| XI | Accessory spinal nerve |

|

|

| XII | Hypoglossal nerve |

|

|

“Some Say Marry Money, But My Brother Says Big Brain Matters More:” CN I is sensory, CN II is sensory, CN III is motor, CN IV is motor, CN V is both (mixed), CN VI is motor, CN VII is both (mixed), CN VIII is sensory, CN IX is both (mixed), CN X is both (mixed), CN XI is motor, and CN XII is motor.

CN VII (Seven) controls Salivation by innervating Submandibular and Sublingual glands.

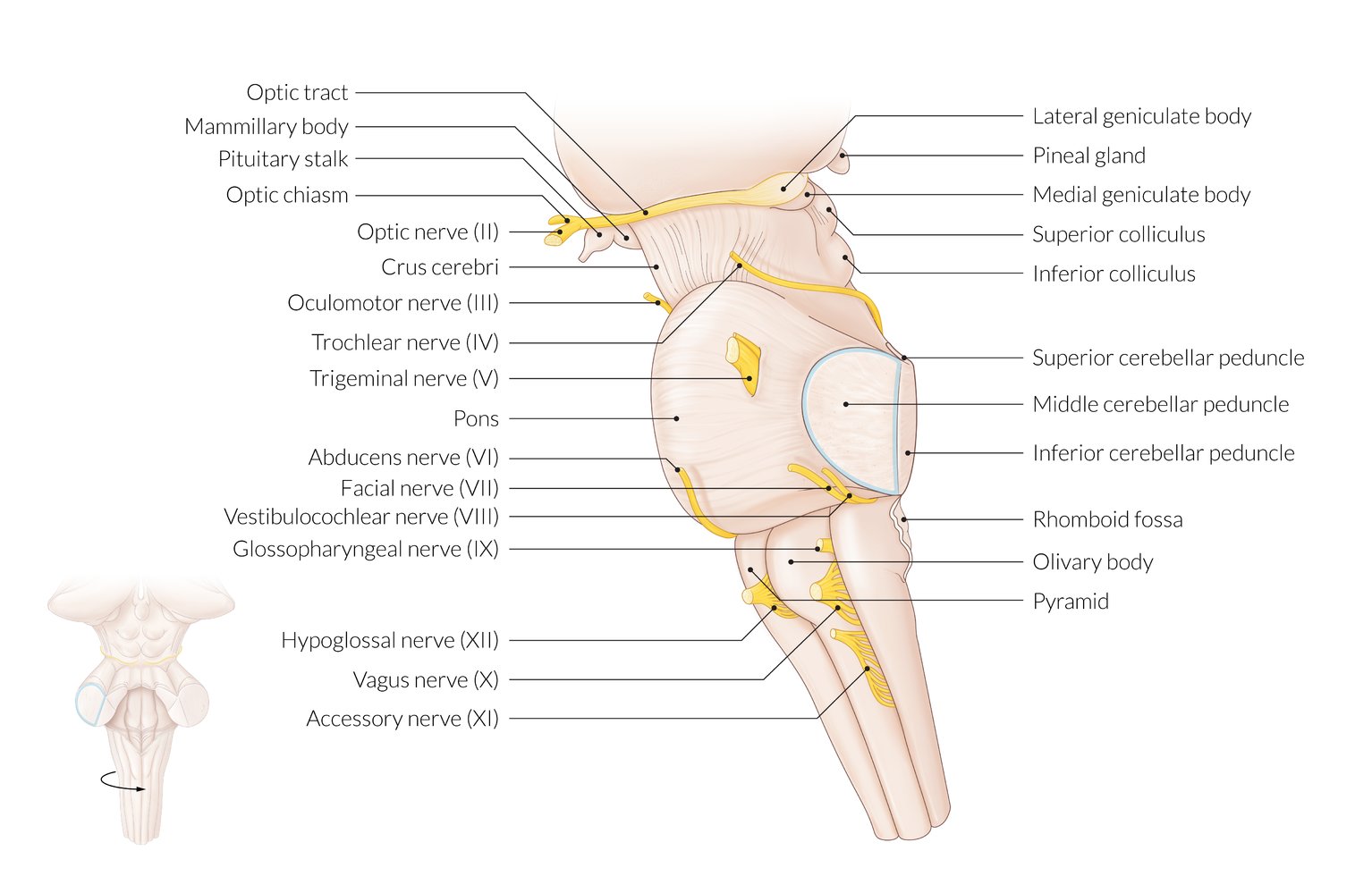

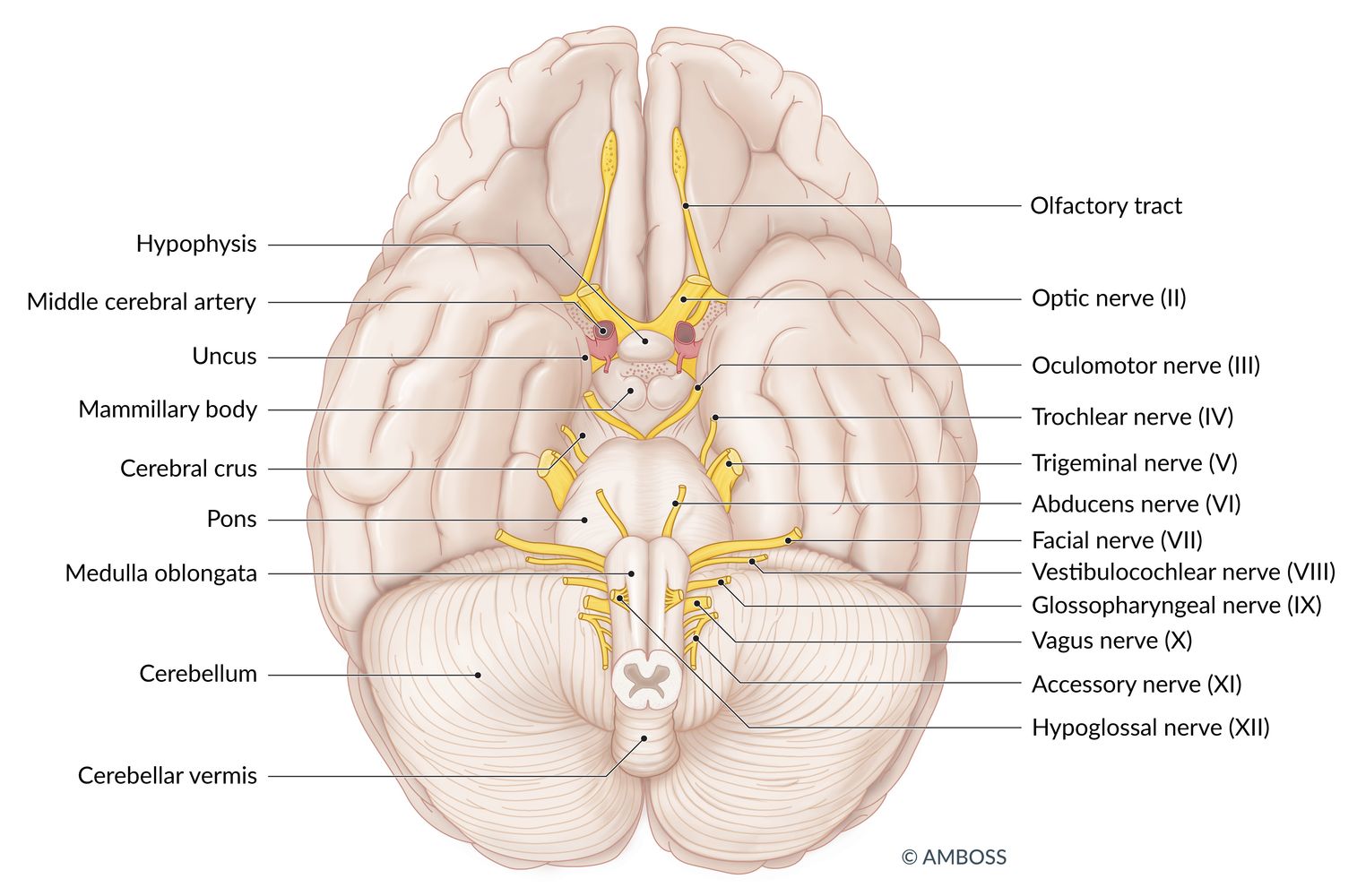

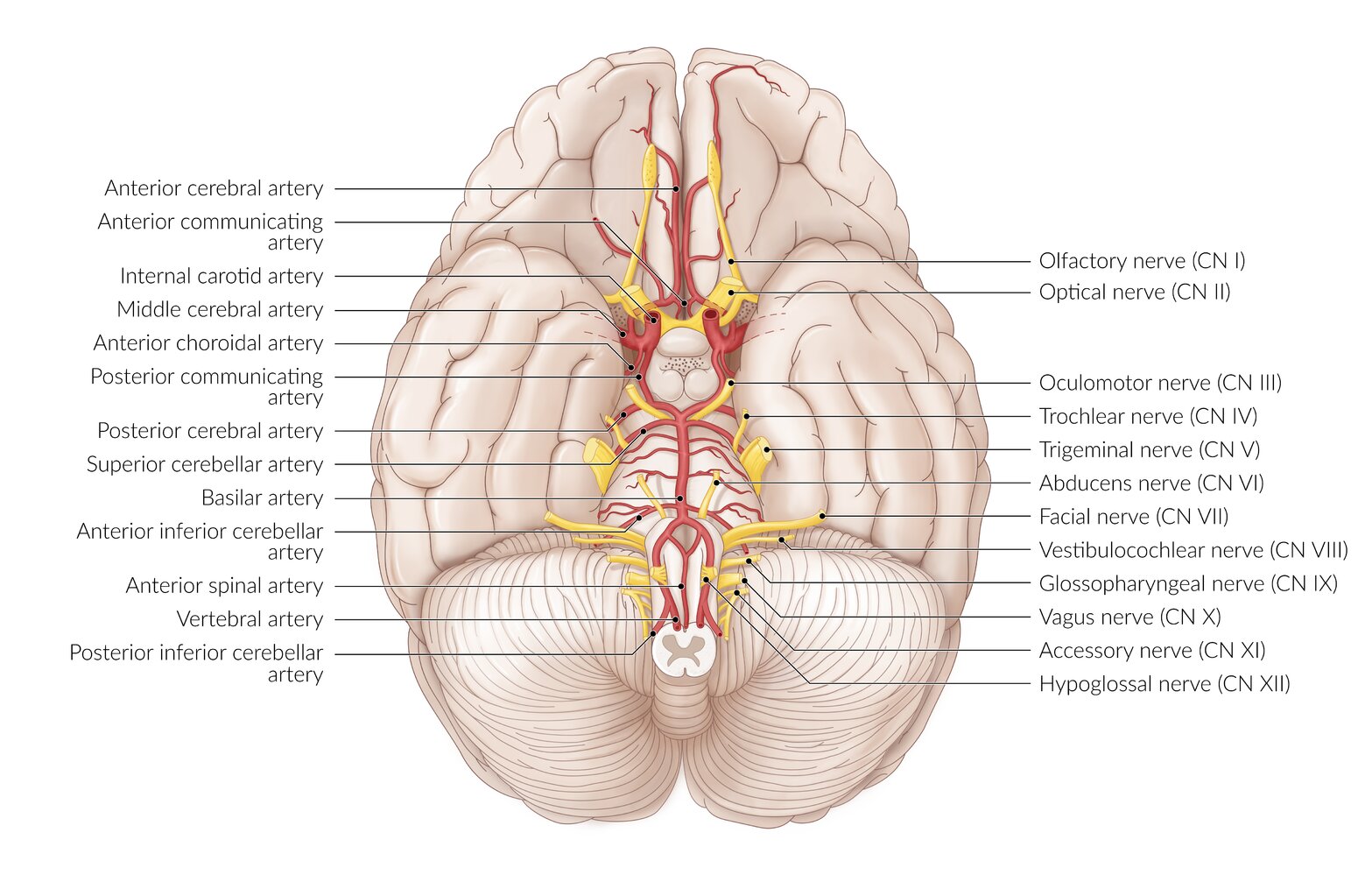

Gross anatomy

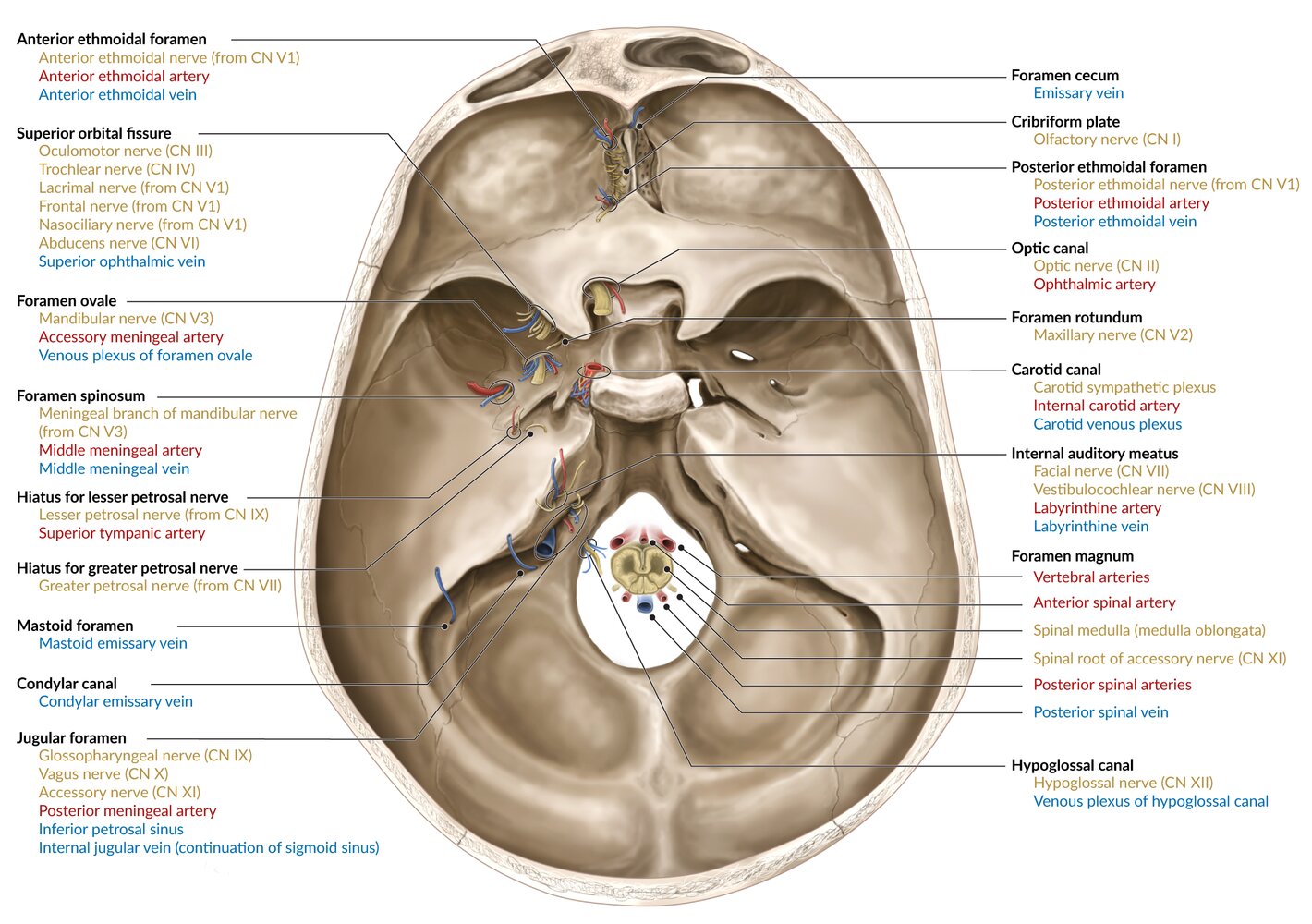

| Origin and pathways of the cranial nerves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranial nerve | Nerve origin | Foramina/Structures | Cranial nerve nuclei | Destination | Pathway |

| CN I |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN II |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN III |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN IV |

|

|

|

|

|

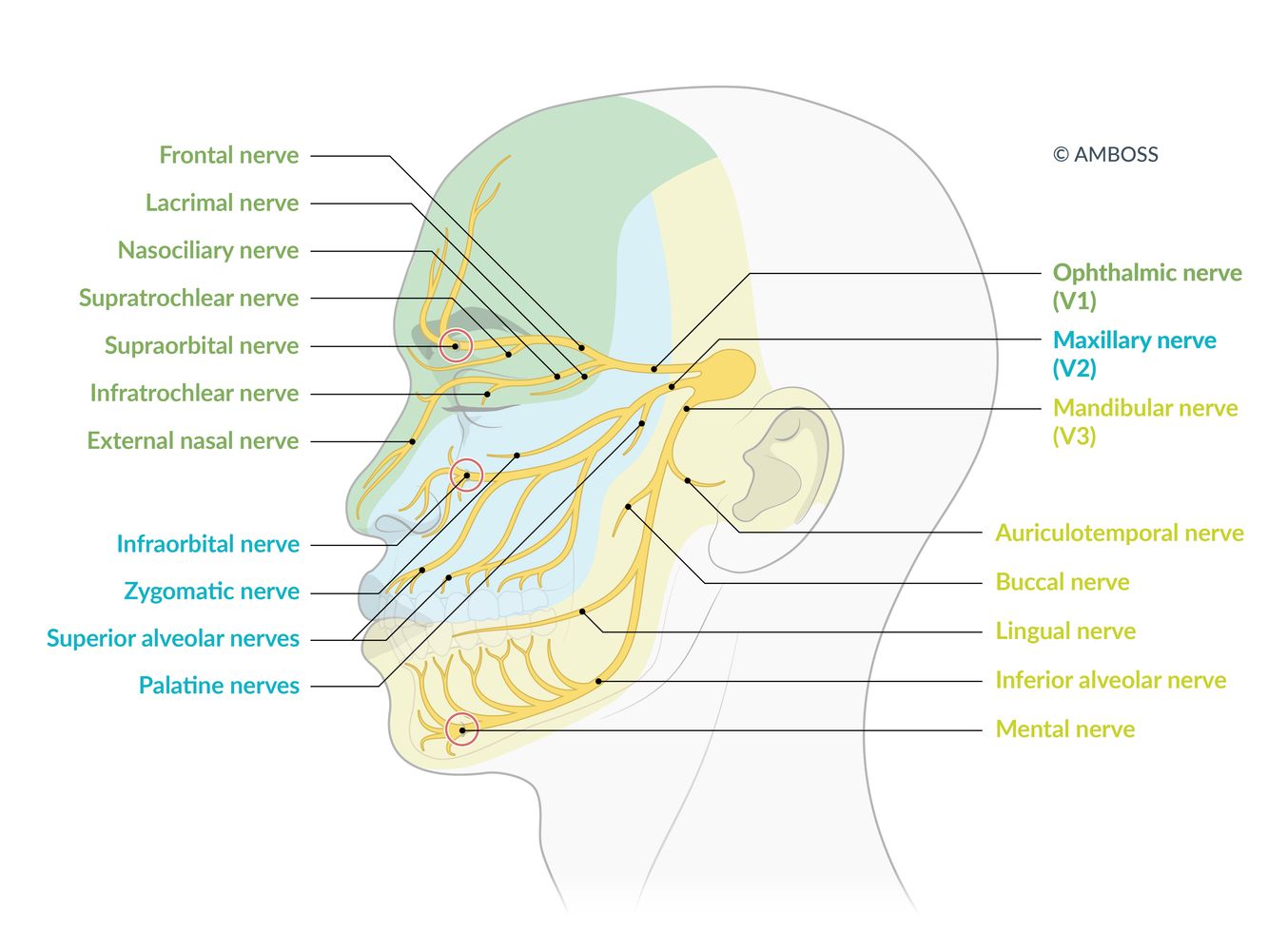

| CN V |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN VI |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN VII |

|

|

|

|

|

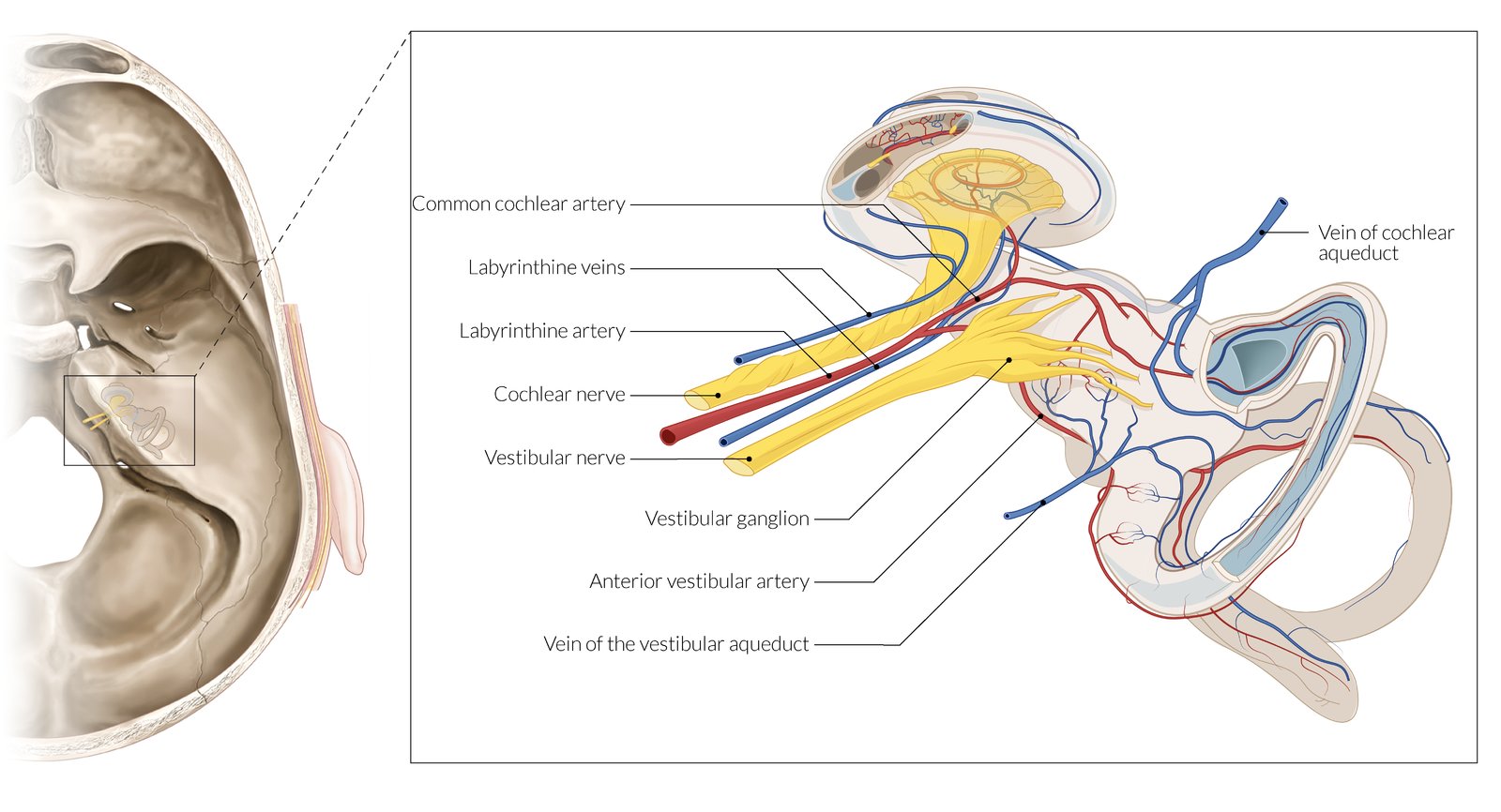

| CN VIII |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN IX |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN X |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN XI |

|

|

|

|

|

| CN XII |

|

|

|

|

|

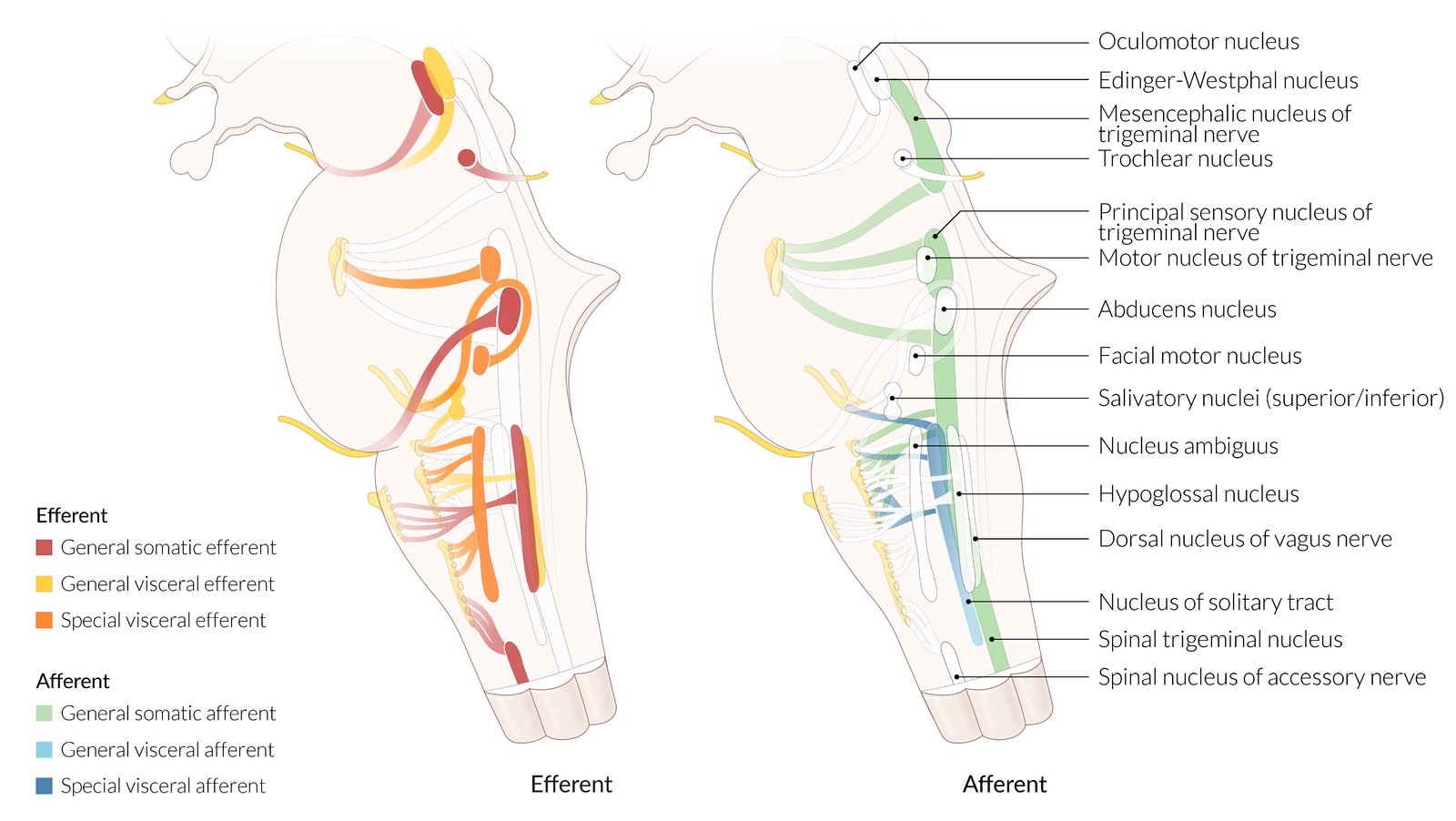

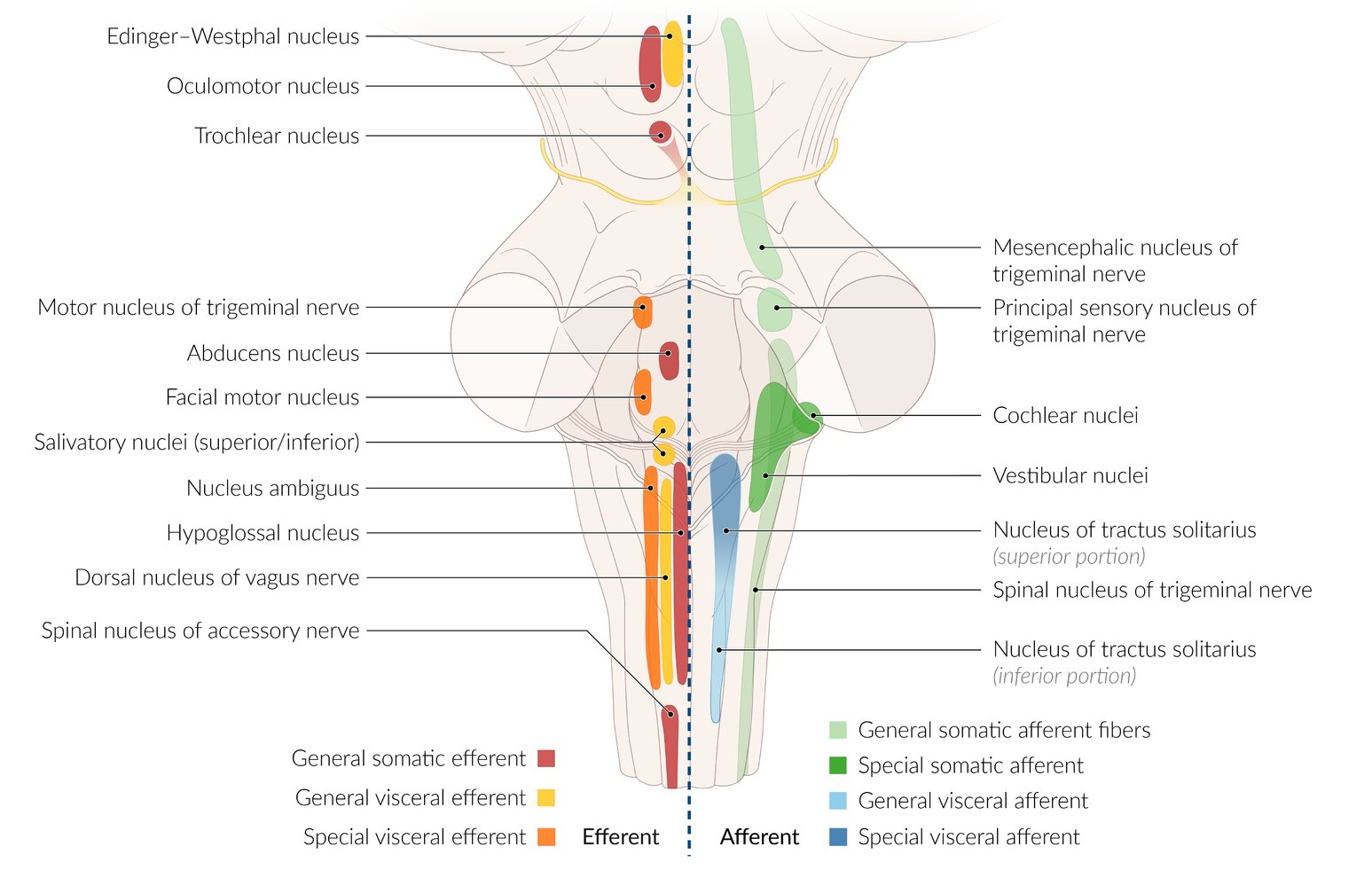

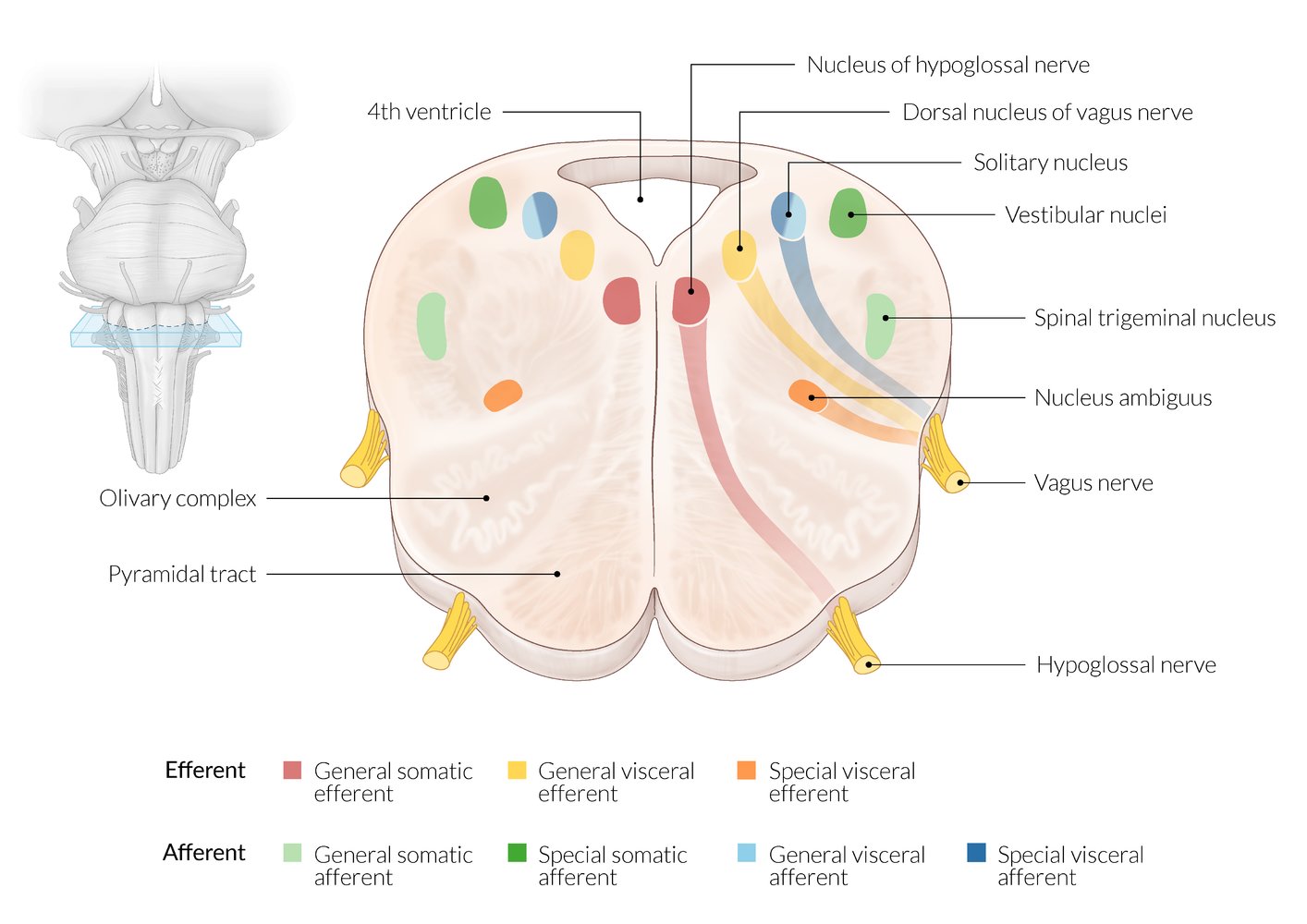

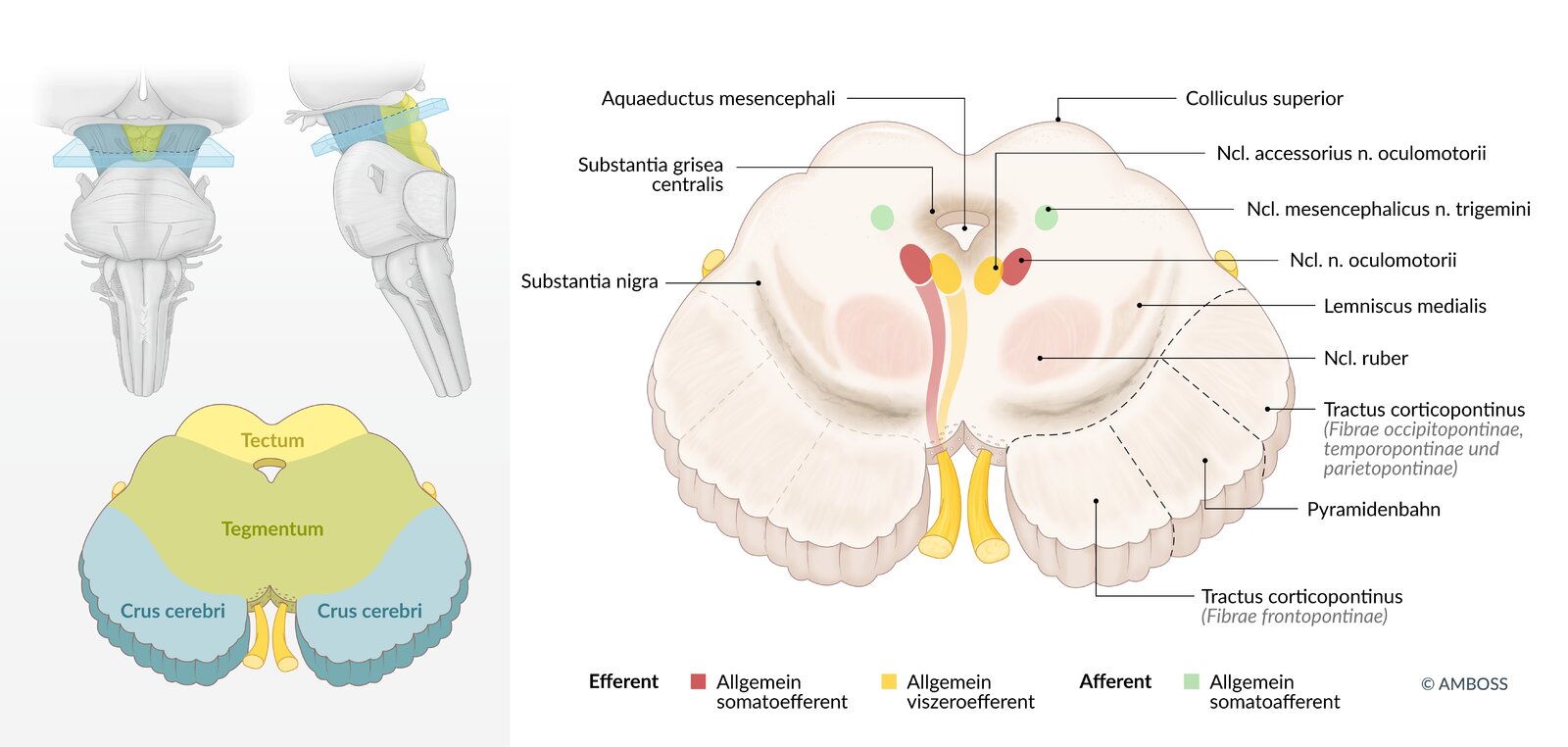

CN I–IV are located in the midbrain, V–VIII in the pons,and IX–XII in the medulla.

The nuclei located in the medial brainstem are factors of 12, except 1 and 2 (i.e., CN III, CN IV, CN VI, and CN XII).

“Standing Room Only”: CN V1 exits through Superior orbital fissure, CN V2 exits through foramen Rotundum, and CN V3 exits through foramen Ovale.

The sulcus limitans in the 4th ventricle separates the CN Motor nuclei in the Medial part of the brain stem (basal plate) from the sensory nuclei in the Lateral part (aLar plate).

3D Anatomy

- Confirm the diagnosis clinically with a cranial nerve examination.

- Consider further evaluation for underlying cause based on clinical suspicion.

- General principles of imaging [16][17][18]

-

MRI (without and with IV contrast)

- Usually the preferred first-line imaging modality for direct imaging of the nerve(s)

- Can also identify soft tissue etiologies (e.g., cavernous sinus thrombosis in CN III–VI palsy)

- CT with IV contrast

- Preferred for the evaluation of bony lesions or skeletal trauma (e.g., orbital fractures, skull base fractures)

- Preferred first line imaging modality to evaluate sinonasal pathology (e.g., in CN I palsy)

- MR angiography: Consider for patients with suspected vascular pathology (e.g., aneurysm for CN III palsy).

-

MRI (without and with IV contrast)

- Laboratory studies (e.g., CBC, inflammatory markers, and antigen-specific ANAs) as needed to evaluate for neoplastic, infectious, inflammatory, or autoimmune etiologies

-

Electromyography (EMG): can be used to assess the severity of nerve injury

- Fibrillation potentials: indicate nerve degeneration

- Polyphasic potentials: indicate nerve regeneration

- Absence of motor action potentials (on EMG in combination with electroeurography): surgical intervention likely needed

- General principles of imaging [16][17][18]

- Consult neurology and other relevant specialties.

- Management includes addressing the underlying cause and supportive care; spontaneous recovery may occur.

Etiology

- Acquired

- Most commonly due to trauma to the lateral and occipital regions (e.g., ethmoid bone fracture)

- Intracranial space-occupying lesion (e.g., meningioma)

- Infection (e.g., meningitis)

-

Congenital

- Primary: congenital anosmia

- Secondary in diseases such as Kallmann syndrome and primary ciliary dyskinesia

Clinical features [16][19]

-

Anosmia (hyposmia or dysosmia may be present instead)

- Sudden anosmia typically occurs secondary to trauma.

- Progressively worsening anosmia is suggestive of an obstructive lesion or a neurodegenerative disease.

- Altered perception of taste

Diagnostics [16][17][20][21]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical and based on:

- Comprehensive history

- Cranial nerve examination: inability to identify certain smells (e.g., peppermint, coffee) [20]

- Assess for common differential diagnoses of olfactory dysfunction, such as sinonasal pathology. [21]

- Perform a head and neck exam.

- Consult otolaryngology for nasal endoscopy.

Further evaluation [20]

Evaluate for the underlying cause.

-

Imaging [16][17][18]

- CT maxillofacial region (with IV contrast): preferred for trauma or suspected sinonasal pathology not confirmed on nasal endoscopy

- MRI head (without and with IV contrast): preferred for a suspected primary neurological cause [18]

- Laboratory studies (e.g., CBC, eosinophil count, thyroid function tests): to evaluate for other etiologies as guided by clinical probability

Treatment

- Consult neurology.

- Address any treatable causes identified.

- Consider a trial of olfactory training. [20][22][23]

- A self-administered therapy in which the patient exposes themselves to 4 different odors for ∼10 seconds twice daily for about 12–24 weeks.

- Associated with improved olfactory sensitivity, especially in olfactory dysfunction secondary to trauma and infections

- Spontaneous recovery (typically over months to years) can occur in up to half the patients with anosmia. [20][21]

Counsel patients on coping strategies such as monitoring for signs of spoiled food and installing smoke and gas detectors. [24]

Etiology

- Acquired

- Ischemic optic neuropathy (i.e., caused by microvascular disease, giant cell arteritis)

- Inflammation (optic neuritis): multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, viral infections (e.g., measles, mumps)

- Trauma

- Tumors: e.g., optic nerve glioma, pituitary adenoma

- Elevated intracranial pressure: e.g., hydrocephalus

- Malnutrition: vitamin B12 deficiency

- Drugs: sildenafil, amiodarone, ethambutol

- Toxins: e.g., ethyl alcohol, mercury, lead

- Congenital

- Primary: optic nerve hypoplasia

- Secondary: infantile nystagmus, sensory strabismus

Clinical features [16]

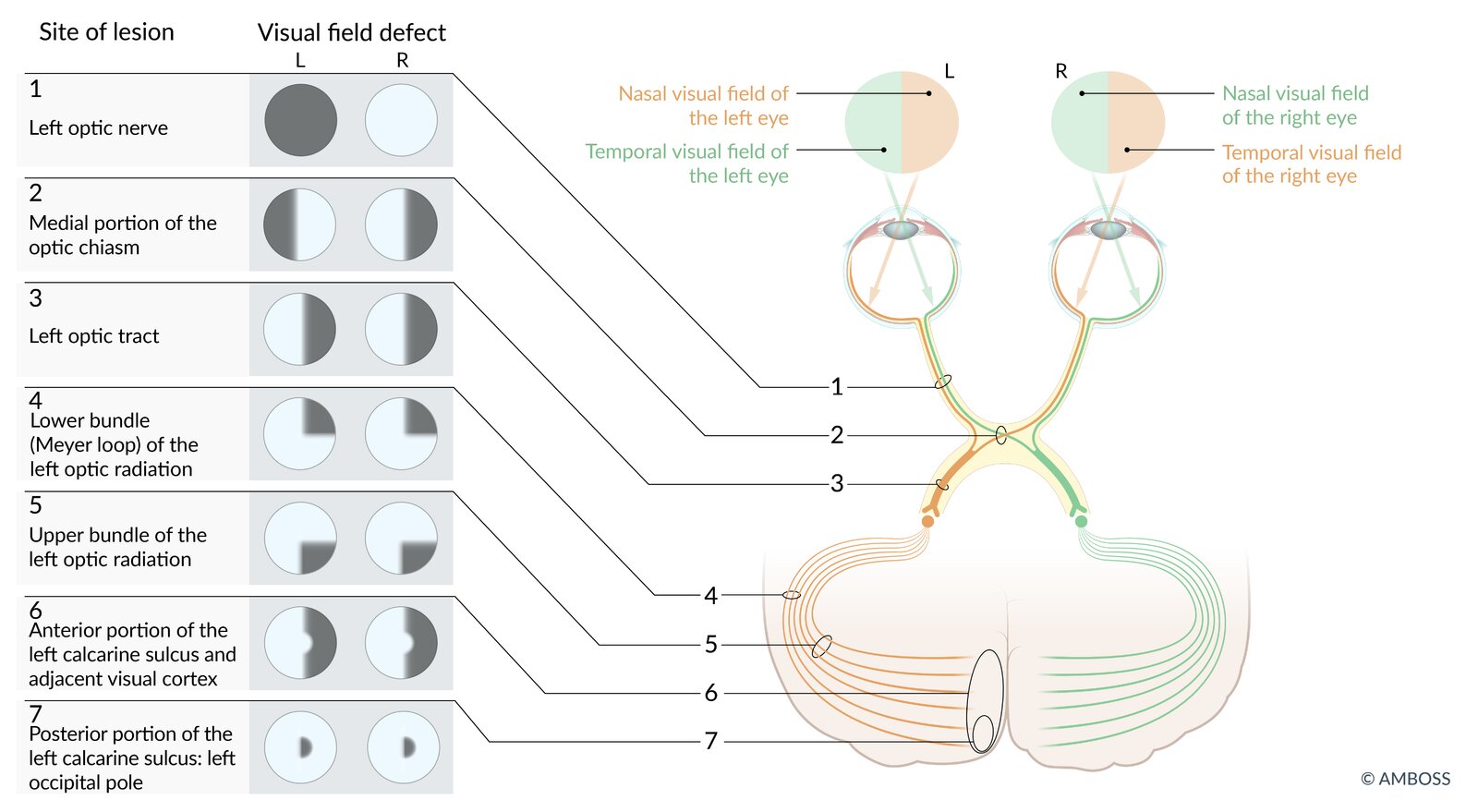

- Impaired vision, including blindness (may start as night blindness), depending on the site of the lesion

- Features of the underlying disease, such as: [25]

- Uhthoff phenomenon in multiple sclerosis

- Jaw claudication and headache in giant cell arteritis

Diagnostics [16][25]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical and based on a comprehensive ocular examination as part of the cranial nerve examination, which includes:

- Assessment of pupillary response, visual field exam, and visual acuity tests

- Complete transection: ipsilateral blindness and loss of direct and indirect pupillary reflex [17]

- Pituitary adenoma (compression to the optic chiasm): bitemporal hemianopia [4]

- Unilateral optic nerve dysfunction: relative afferent pupillary defect [25][26]

-

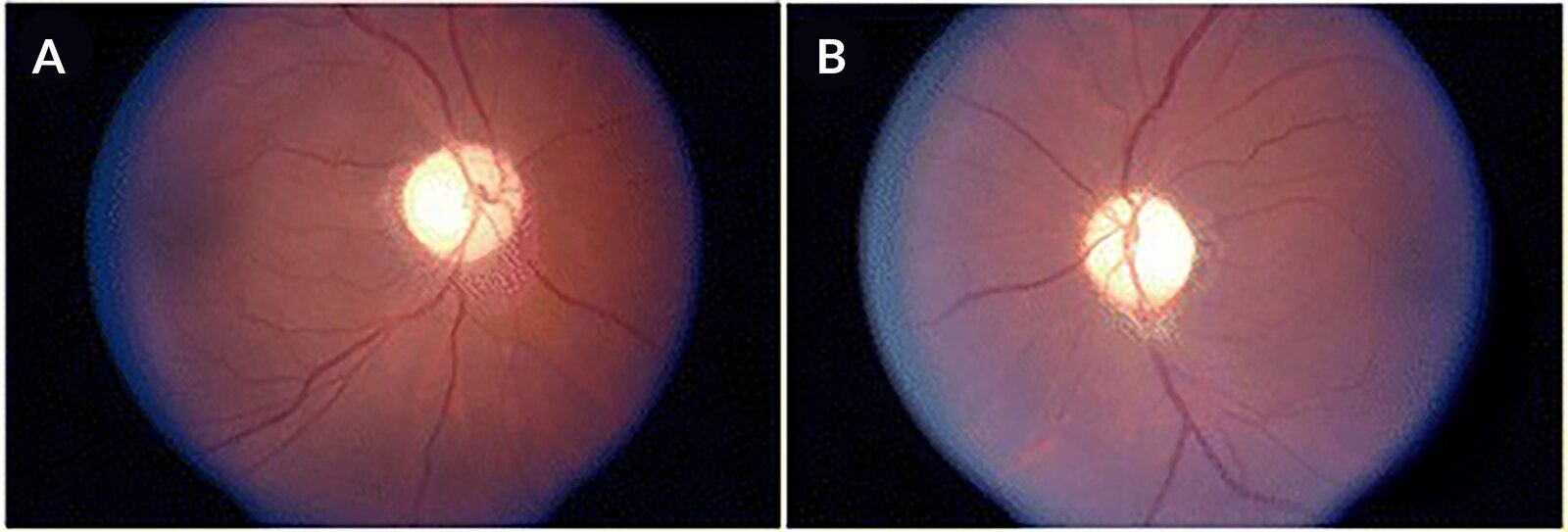

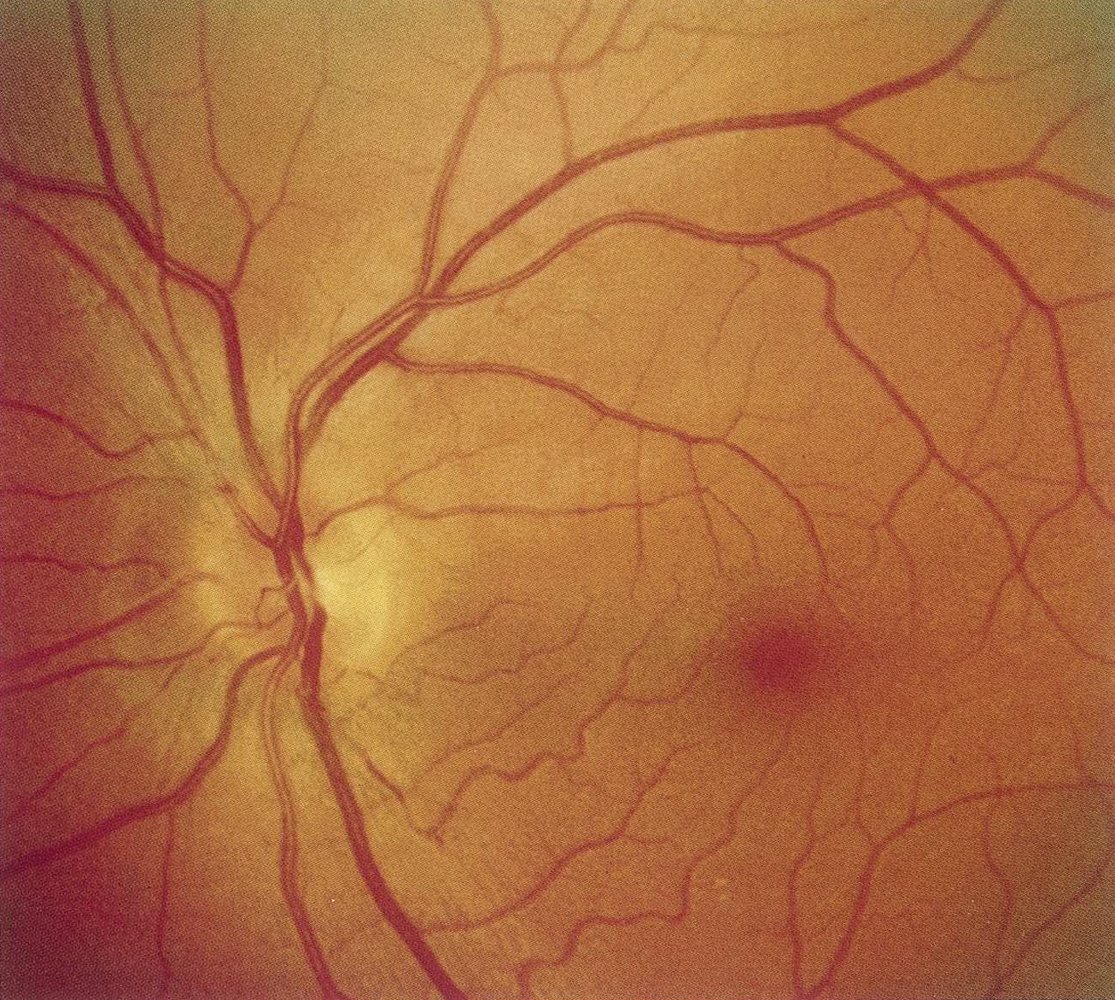

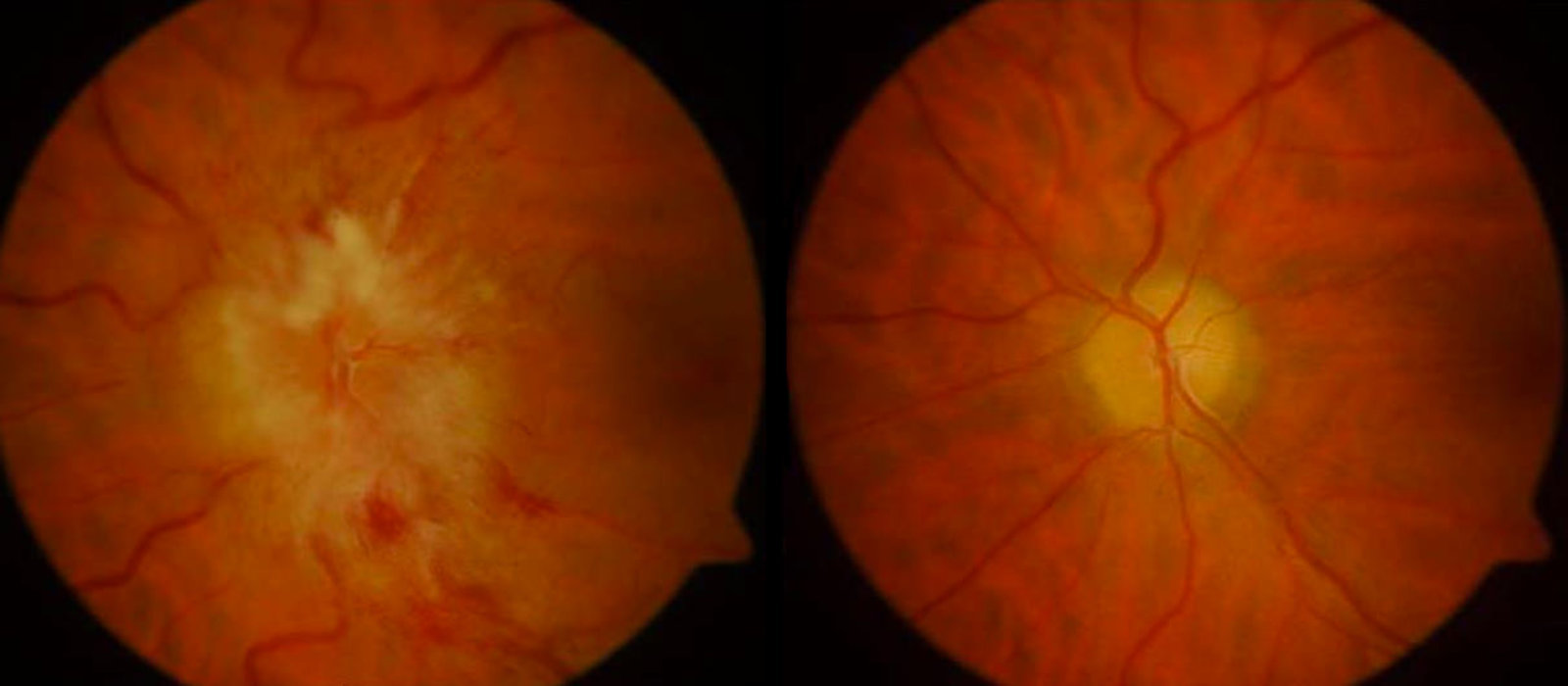

Fundoscopy: findings depend on the underlying cause and include

- Papillitis

- Papilledema in ↑ ICP

- Optic atrophy in compression (e.g., tumor)

Further evaluation[27]

Consider further evaluation for underlying cause based on clinical findings.

-

Imaging [17]

- CT head (without IV contrast): initial evaluation of trauma or orbital complications of sinusitis

- MRI head and orbits (with IV contrast): initial evaluation of suspected tumor, optic neuritis, or neurodegenerative diseases

-

Laboratory studies to evaluate for the underlying cause (as guided by clinical probability); examples include: [28][29]

- ESR and CRP

- ANA and antigen-specific ANAs

- Toxic exposure tests

Treatment [16][25]

- Address any underlying etiologies identified.

- Consult neurosurgery and/or ophthalmology.

- Traumatic CN II palsy: Options include surgery, high-dose corticosteroids, and observation.

Etiology

| Etiology of CN III palsy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Cause | Clinical features |

| Oculomotor nuclei |

|

|

| Basilar segment |

|

|

|

|

|

| Intracavernous segment |

|

|

| Intraorbital segment |

|

|

| Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy |

|

|

Parasympathetic fibers of CN III are located superficially and motor fibers are located centrally. Parasympathetic fibers are more susceptible to compressive lesions (e.g., uncal herniation, aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery). Motor fibers are more susceptible to ischemia (e.g., vasculitis, diabetes, atherosclerosis).

Clinical features [31]

- Horizontaldiplopia that worsens when the head is turned away from the side of the lesion

- Ptosis

- Light sensitivity

- Additional features may be present, depending on the cause and the level of the oculomotor nerve lesion.

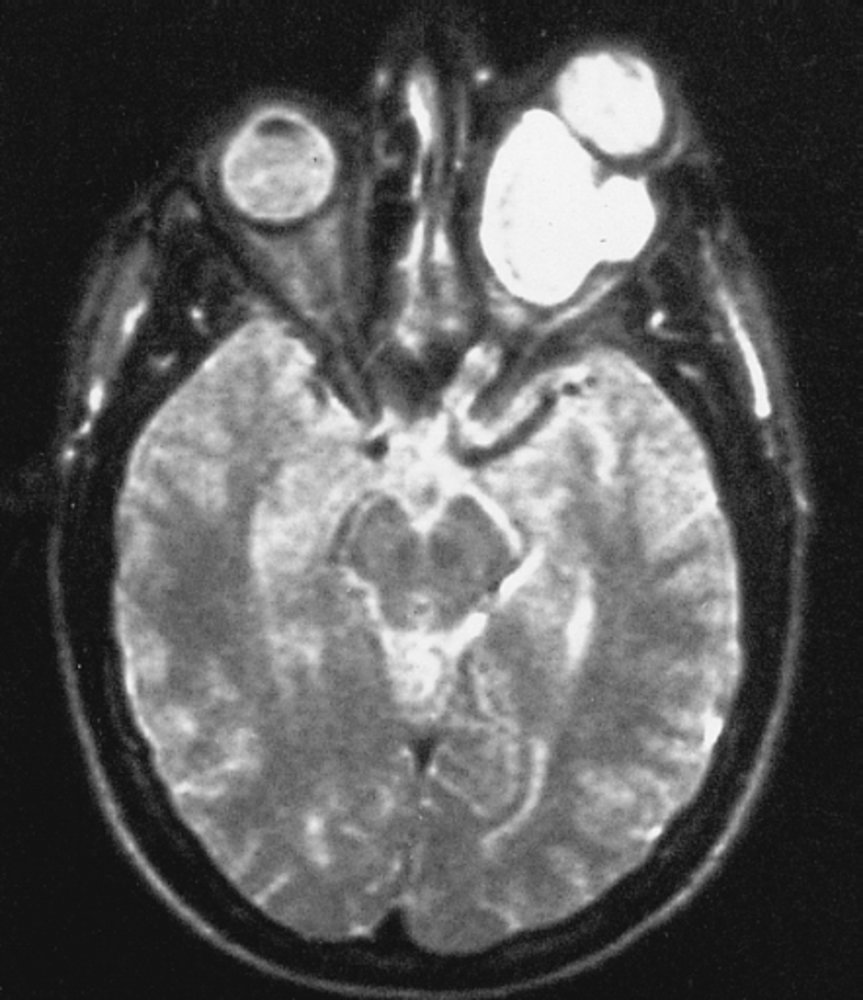

Diagnostics [16][31]

Cranial nerve examination

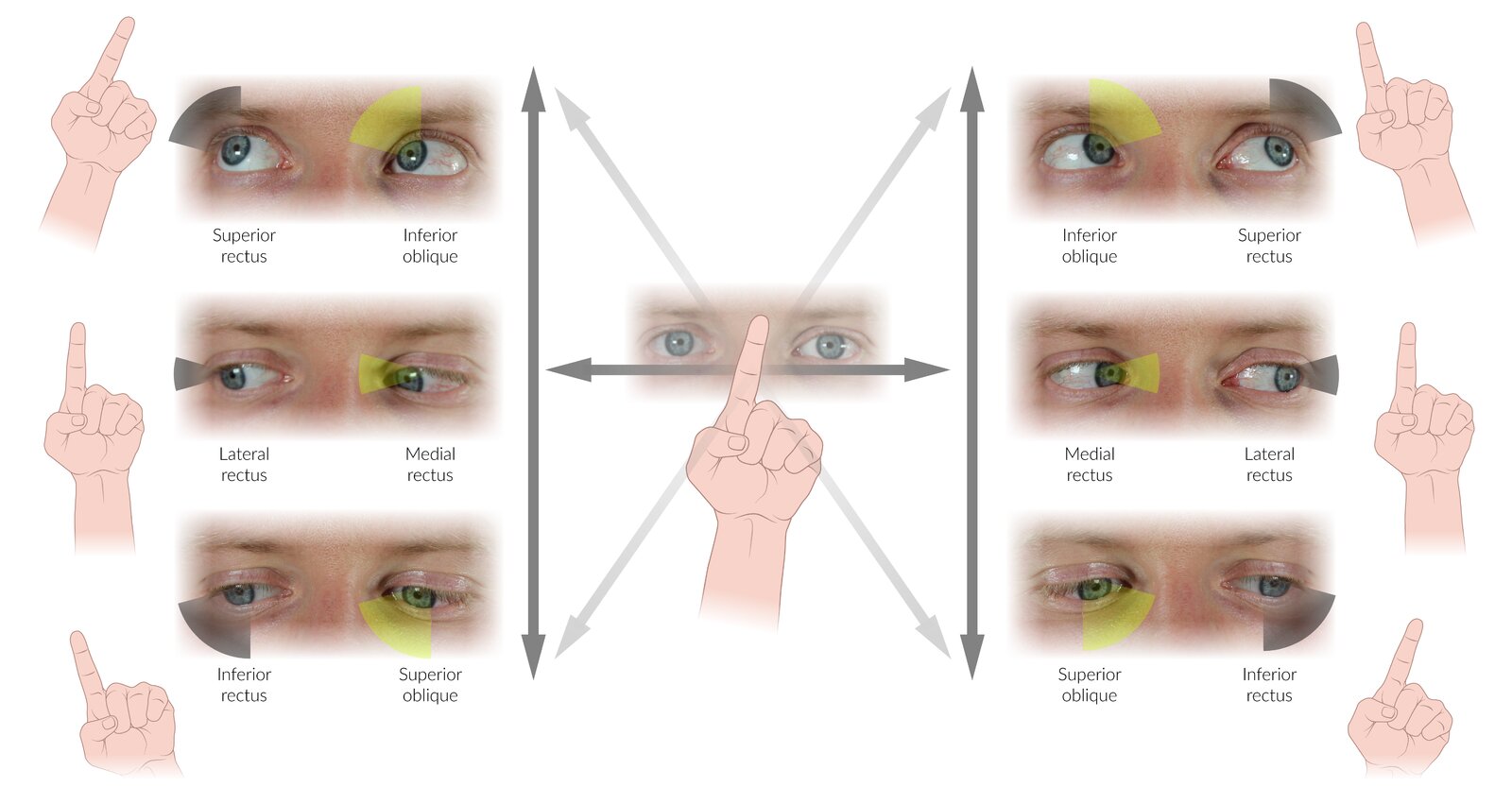

Diagnosis is clinical and based on a comprehensive ocular examination as part of the cranial nerve examination.

-

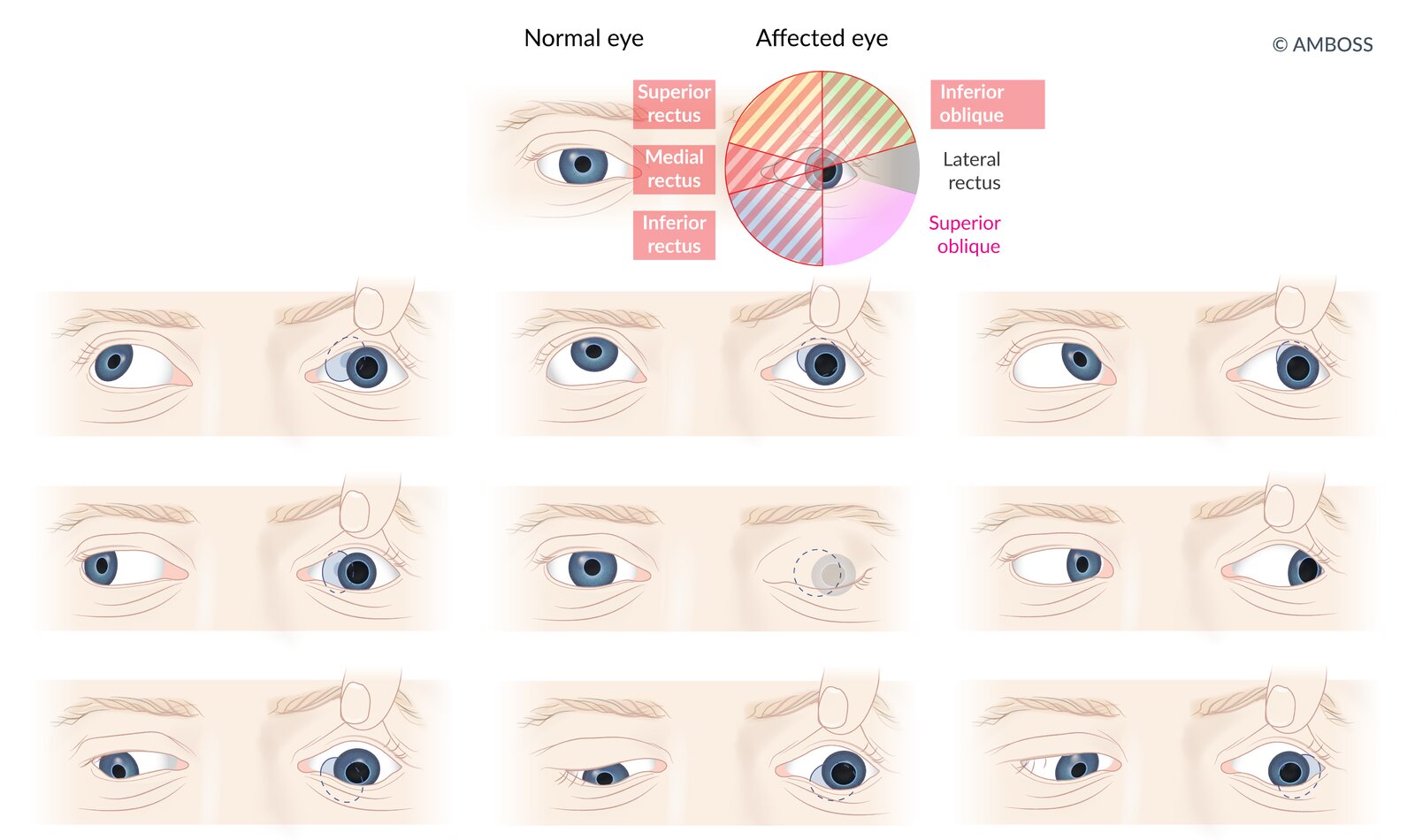

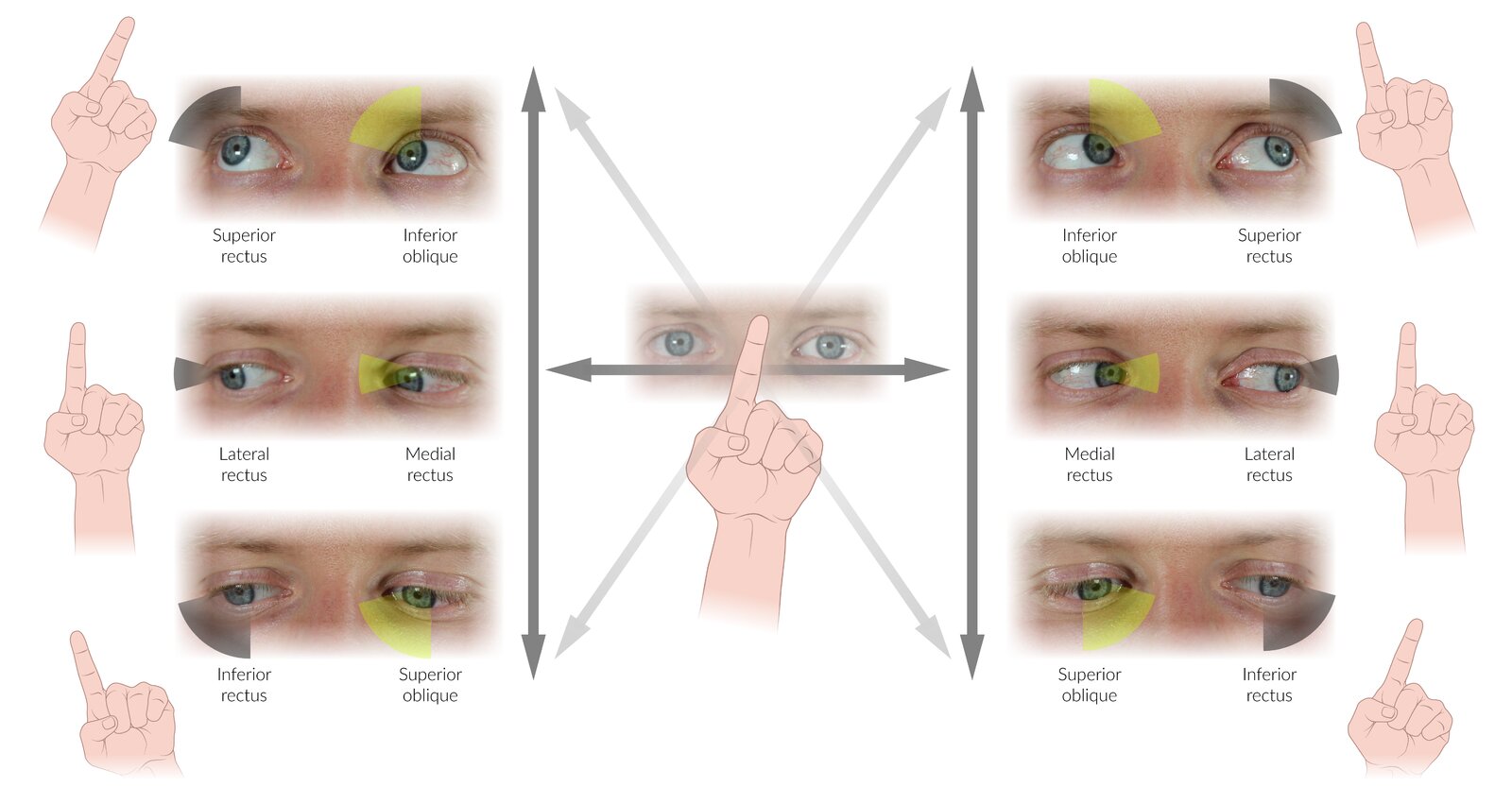

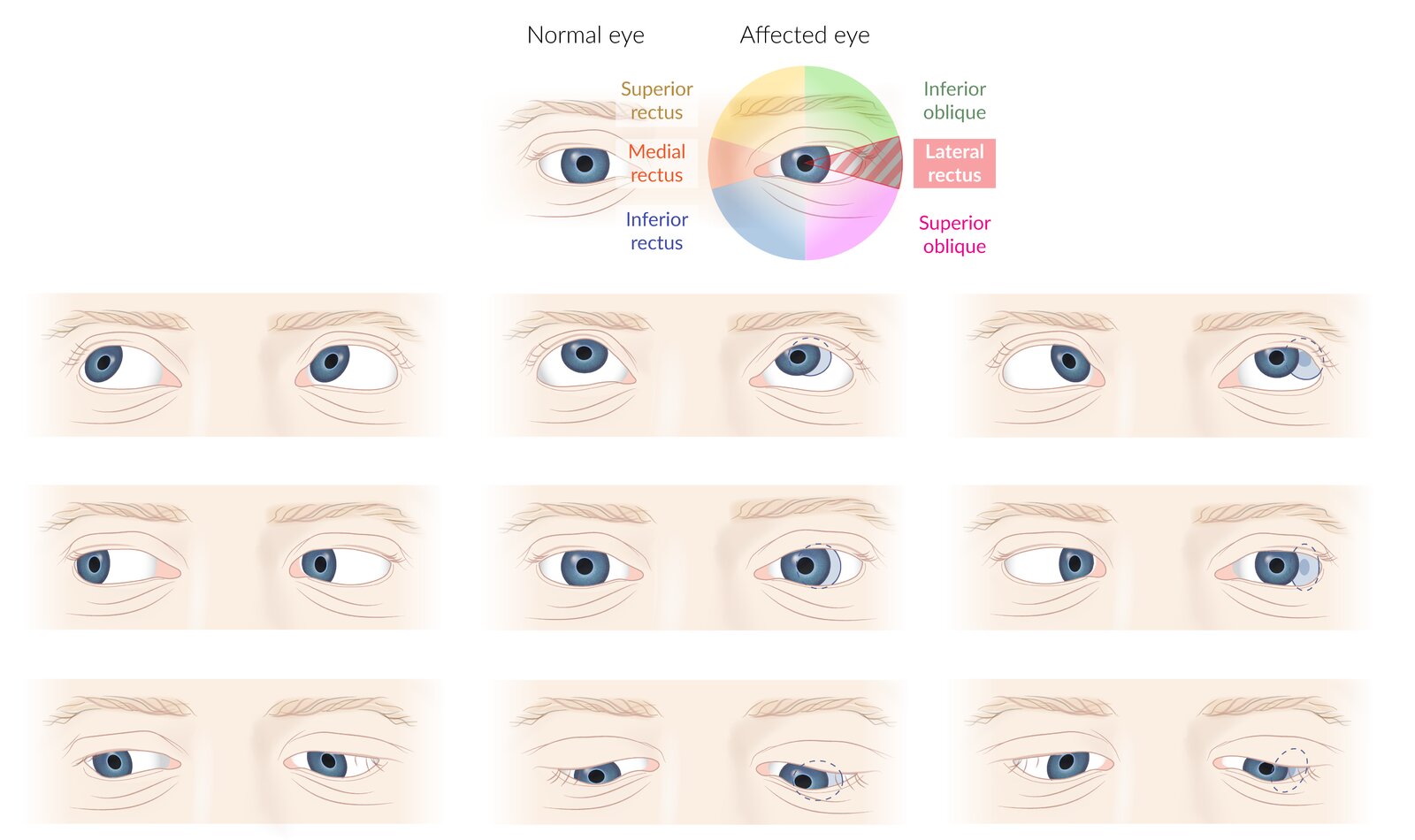

Assessment of extraocular muscle function : Lesions of the motor portion typically produce paralytic squint.

- Down-and-out gaze: affected eye looks outwards (exotropia) and downwards (hypotropia)

- Adduction weakness

-

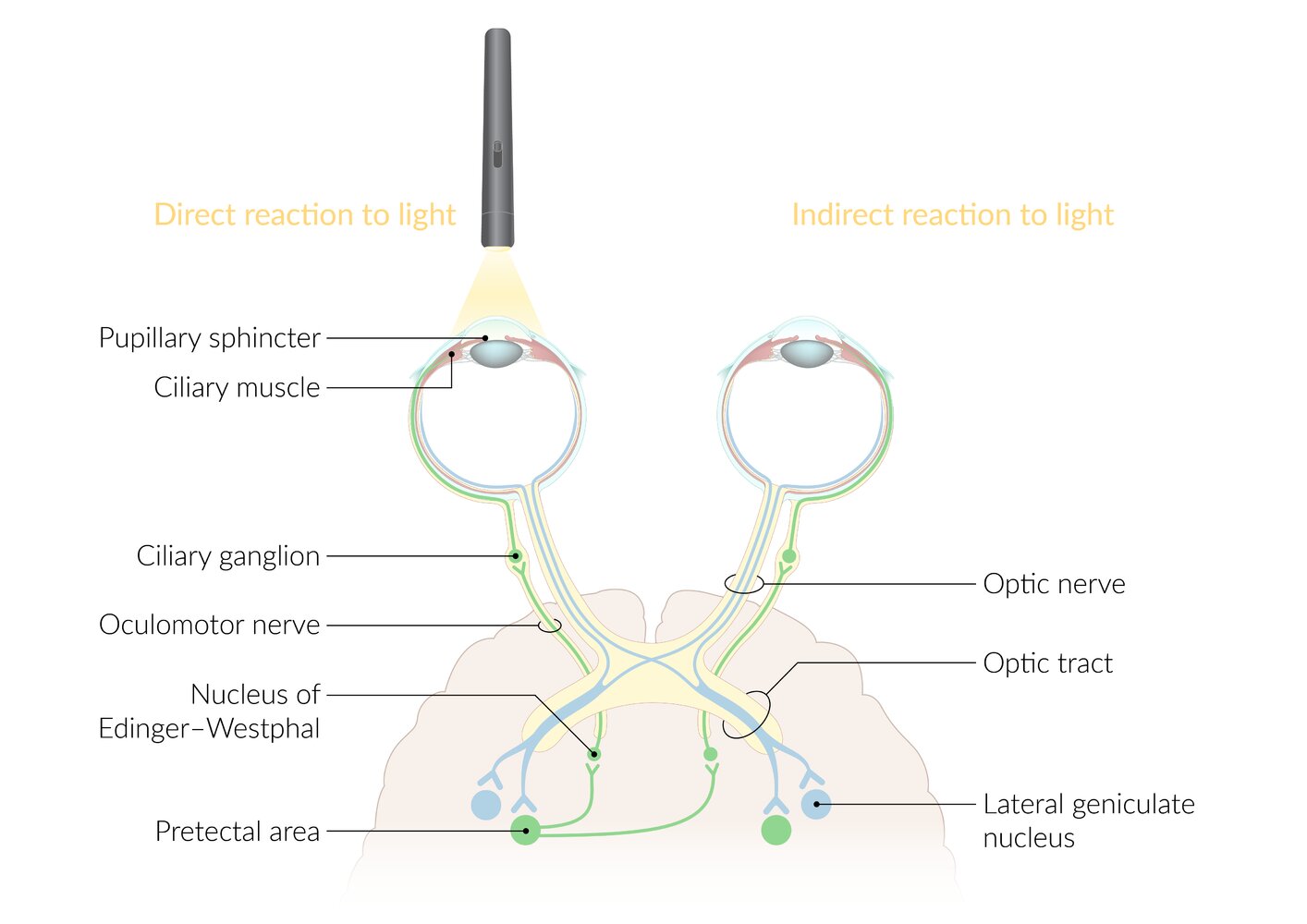

Assessment of pupillary response (afferent: CN II; efferent: CN III)

- Lesions of the autonomic (parasympathetic) portion result in loss of the pupillary reflex.

- See also “Physiology and abnormalities of the pupil” for details on oculomotor nerve lesions and drugs that affect pupillary size.

Oculomotor nerve palsy leaves you down and out.

Impaired pupillary reaction with relative sparing of motor function is typically seen in compressive lesions. Prominent motor dysfunction with sparing of the pupil is typically seen in ischemic lesions. However, pupillary findings cannot reliably distinguish between the etiologies of oculomotor palsy. [28][32][33]

Further evaluation

Evaluate for underlying cause based on clinical findings.

| Workup for suspected CN III palsy [17][27] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical findings | Likely underlying cause | Further evaluation |

| Complete palsy with dilated pupil OR Incomplete palsy regardless of pupillary findings |

|

|

| Complete palsy with a normal pupillary reflex (pupillary sparing) |

|

|

MRI orbits (without and with IV contrast) should be obtained in patients with ophthalmoplegia and a history of trauma, or those with evidence of orbital injury or inflammation (i.e., enopthalmos, proptosis, chemosis). [27]

MRI head should also be obtained in patients ≤ 50 years old with a history of cancer and additional neurologic findings, including nonisolated cranial nerve palsy. [34]

Treatment [16][31]

-

Compressive lesions

- Immediate neurosurgery referral for management

- Posterior communicating artery aneurysm requires urgent neurosurgical clipping or endovascular coiling [36][37]

- Consider strabismus surgery if symptoms do not improve after treatment of the underlying cause.

-

Ischemic microangiopathy or demyelinating lesions

- Medical management with control of the underlying disease

- Ischemic CN III palsy typically resolves spontaneously within 6–8 weeks. [17][31]

- Prism glasses or an eye patch can be used to improve diplopia while awaiting resolution.

Motor fibers are in the Middle of CN III, while Parasympathetic fibers are on the Periphery of the nerve.

Etiology

- Acquired

- Microvascular damage (diabetes, hypertension, arteriosclerosis)

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Trauma

- Congenital: fourth nerve palsy

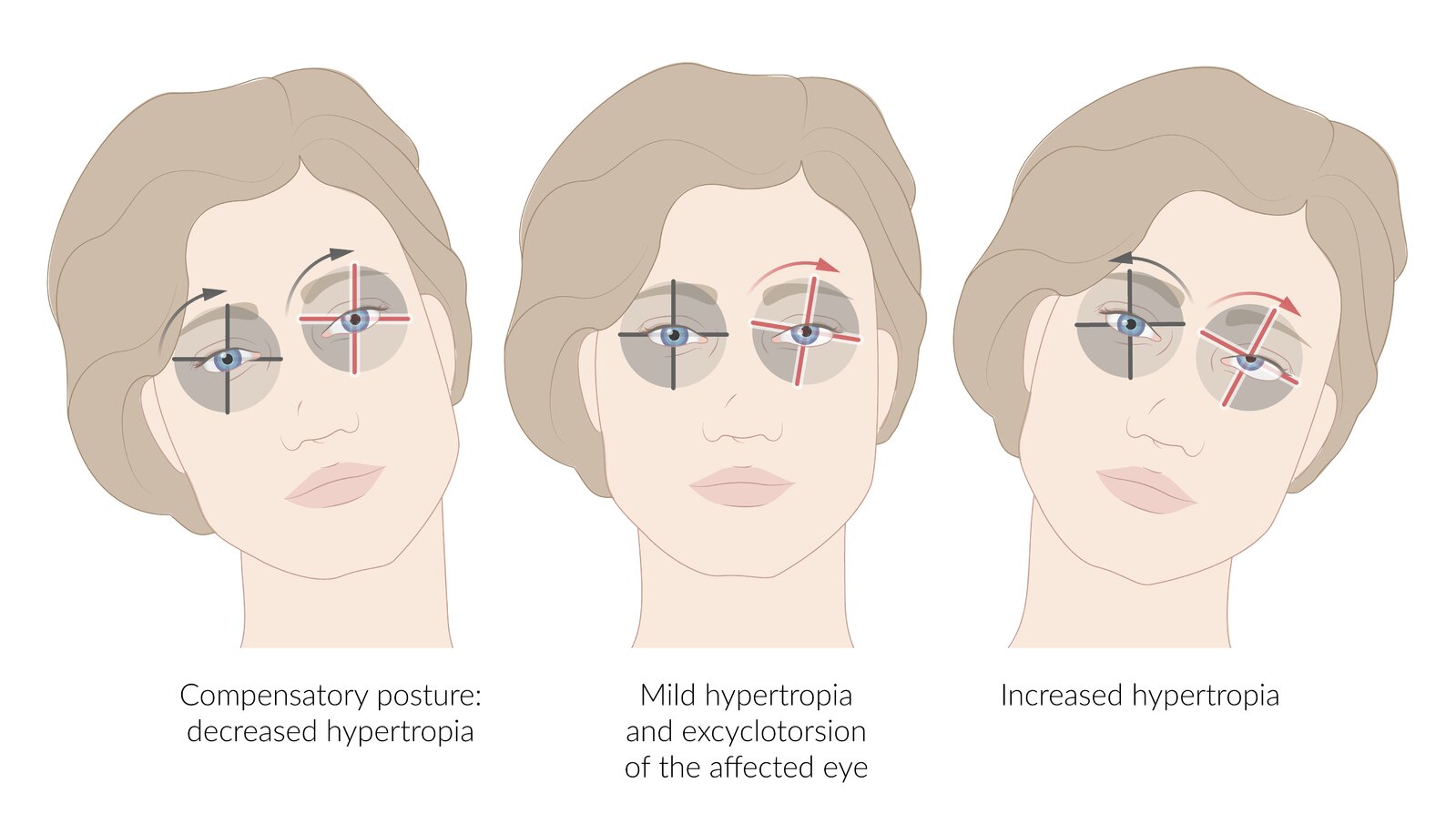

Clinical features

- Vertical or oblique diplopia

- Exacerbated on downgaze (e.g., reading, walking downstairs) away from side of affected muscle [38]

- Worsens when patient turns the head towards the paralyzed muscle →compensatory head tilt to the opposite side of the lesion

With damage to the CN IV, you cannot look at the floor.

Diagnostics

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on cranial nerve examination, which includes: [38][39]

-

Assessment of extraocular muscle function

- Extorsion of the eye

- Inability to depress and adduct the eyeball simultaneously

- Park-Bielchowsky test: ipsilateral hypertropia that worsens on contralateral gaze and ipsilateral head tilt

Imaging [17][27][34]

- Not routinely required

- Consider MRI head and orbits (without and with IV contrast) in consultation with a neurologist in the following situations

- History of trauma

- Patients ≤ 50 years old with a history of cancer and additional neurologic findings, including nonisolated cranial nerve palsy

- Persistent palsy after 3 months (in all age groups)

- Progression of symptoms

Treatment [16][40]

- Consult neurology and ophthalmology.

- Symptoms often resolve spontaneously within six months of onset.

- Prism glasses or an eye patch can be used to improve diplopia while awaiting resolution.

- Surgical realignment may be needed for persistent CN IV palsy.

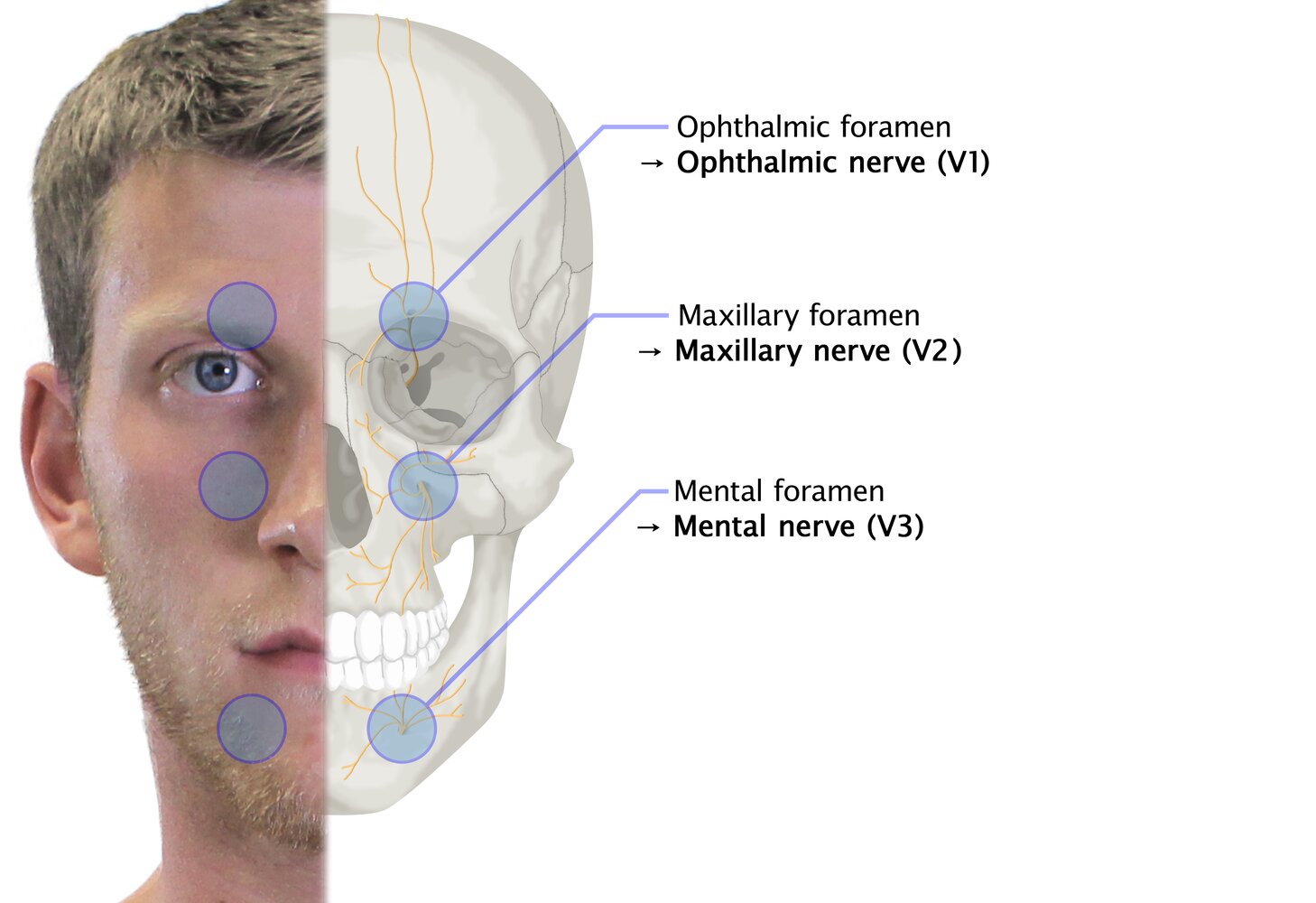

Etiology

- Tumor

- Vascular compression

- Trauma, including maxillofacial or oral surgery, and mandibular molar extractions

- Inflammation of the nerve

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

Clinical features

Clinical features depend on the site of the lesion and can include (see “Localizing features of CN V palsy” for details):

- Altered sensation over the face and tongue

- Weakness in muscles of mastication

- Hearing impairment

Diagnostics [16][41]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on ear examination, nose and throat examination, and cranial nerve examination.

- Assess for decreased facial sensation to light touch, pain (can also be increased), and/or temperature (CN V1, V2).

- Assess for diminished/absent corneal reflex or lacrimation reflex (CN V1).

-

Assess muscles of mastication (CN V3) for:

- Signs of atrophy

- Decreased strength (e.g., open mouth against resistance)

- Jaw jerk reflex

| Localizing features of CN V palsy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral trigeminal nerve lesions | Ophthalmic nerve (CN V1) |

|

| Maxillary nerve (CN V2) |

|

|

| Mandibular nerve (CN V3) |

|

|

| Lesion of the tensor tympani branch |

|

|

| Lesions of the trigeminal nerve nuclei (depending on the nuclei affected) |

|

|

The primary features of trigeminal neuropathy are numbness and/or weakness in the areas of trigeminal nerve innervation, whereas the primary feature of trigeminal neuralgia is intermittent sharp pain in the same area without sensory or motor deficits. [41]

Further evaluation

Consider further evaluation for underlying cause based on clinical findings.

-

Imaging [16][17][41]

- Not routinely required if the underlying cause is clear (e.g., peripheral paresthesia following mandibular molar extraction)

- History of head trauma: Consider CT head and skull base.

- Suspected intracranial hemorrhage, tumor, cavernous sinus thrombosis : MRI head (without and with IV contrast)

- Laboratory studies (as needed): e.g., CBC, ESR, RPR, ANA and antigen-specific ANAs

Treatment [16][41]

- Consult neurology and maxillofacial surgery.

- Traumatic CN V palsy (e.g., following dental surgery) often resolves spontaneously within six months of symptom onset.

- Consider adjuvant analgesics as needed for pain.

- Treat the underlying cause (e.g., see “Treatment of cavernous sinus thrombosis”).

- Screen for and treat complications.

- Monitor for tongue and mouth injuries due to decreased sensation.

- Screen for inadequate nutrition due to weak mastication.

- Consider biofeedback training for chronic pain and weakness.

- Screen for corneal edema due to absent corneal reflex; consider protective contact lenses.

- Screen for symptoms of depression.

Etiology [10][42]

- Acquired

- Trauma (e.g., at the superior orbital fissure)

- Pseudotumor cerebri

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Space-occupying lesion causing downward pressure (e.g., tumor)

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

- Congenital: Duane syndrome (a rare type of strabismus characterized by an impaired abduction and ptosis on adduction) [43]

Abducens nerve palsy is the most common ocular cranial nerve palsy.

Clinical features

- Horizontal diplopia that worsens when looking at distant objects

- Inability to look laterally in the affected eye

- Features of the underlying cause

Diagnostics [42][44]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the examination of the extraocular muscles as part of the cranial nerve examination.

- Esotropia: medial deviation of the affected eye at primary gaze

- Inability to abduct the affected eye

Further evaluation [42]

Evaluate for underlying cause based on clinical findings.

-

MRI head and orbits (with IV contrast) if any of the following are present: [17][34][42][44]

- Patients < 50 years of age

- History of cancer

- No ischemic risk factors

- Additional neurologic findings, including nonisolated cranial nerve palsy

- No evidence of resolution after 3 months

- Evaluation of all other patients (or patients with normal neuroimaging): [42][44]

- Consult neurology and/or ophthalmology.

- Assess for ischemic risk factors : e.g., Check blood pressure, blood glucose, lipid profile, ESR.

- Assess for underlying infection, autoimmune etiologies, or mimics (e.g., thyroid eye disease, myasthenia gravis) as needed.

- CBC, ANA

- Syphilis diagnostics,

- Thyroid function tests, AChR antibody levels

- Consider lumbar puncture.

Treatment

- Consult neurology and ophthalmology.

- Treat the underlying cause.

- Complete resolution of isolated CN VI palsy is seen in 75–88% of patients within 6 months of symptom onset. [42]

- Prism glasses or eye patching may be considered to manage disabling diplopia.

- Consider strabismus surgery for chronic CN VI palsy.[45]

- See “Facial nerve palsy.”

Etiology

- Bacterial meningitis (most common cranial nerve palsy)

- Lyme disease

- Tumor (e.g., acoustic neuroma, neurofibromatosis type 2)

- Trauma: basilar skull fracture (damage to the CN VIII within the internal acoustic meatus → symptoms of vestibular and cochlear nerve damage)

Clinical features

- Hearing loss

- Vertigo

- Motion sickness [46]

- Tinnitus

Diagnostics [47][48]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on a comprehensive examination of the ears, hearing, and vestibular system, as part of the cranial nerve examination.

- Evaluation of cochlear nerve function (Rinne test, Weber test, audiometry) : sensorineural hearing loss

- Evaluation of vestibular nerve function (HINTS exam, vestibular function tests): features of peripheral vertigo (see “Peripheral vs. central vertigo”)

- Abnormal head impulse test

- Horizontal nystagmus; gaze fixation suppresses nystagmus

- Skew deviation is absent

If a tuning fork is unavailable, a hum test may be used as an alternative to the Weber test [48]

In patients with sudden hearing loss, audiometry should be performed within 14 days from the onset of symptoms. [48]

Further evaluation

Consider further evaluation for underlying cause based on clinical findings.

- Laboratory studies as needed: e.g., CBC, ANA, or testing for Lyme disease, syphilis, TB, or HIV

- Imaging: MRI head and brainstem with IV contrast (to assess for, e.g., vestibular schwannoma, multiple sclerosis, TIA) [17][48]

Treatment [48]

- Consult neurology and/or otolaryngology.

- Treatment is aimed at resolving underlying causes (e.g., surgical excision and/or radiation for a tumor).

- Consider expectant management with scheduled repeat audiometry to assess for spontaneous recovery.

- For severe sensorineural hearing loss, consider initial treatment with prednisone within two weeks of symptom onset. [48]

Etiology

- Idiopathic

- Compression (e.g., aneurysm, tumor, retropharyngeal abscess)

- Trauma (skull base fractures)

Clinical features

Isolated CN IX palsy is rare and may be asymptomatic due to shared sensory and motor nuclei with adjacent nerves. [49]

- Throat and ear pain (glossopharyngeal neuralgia)

- Mild dysphagia

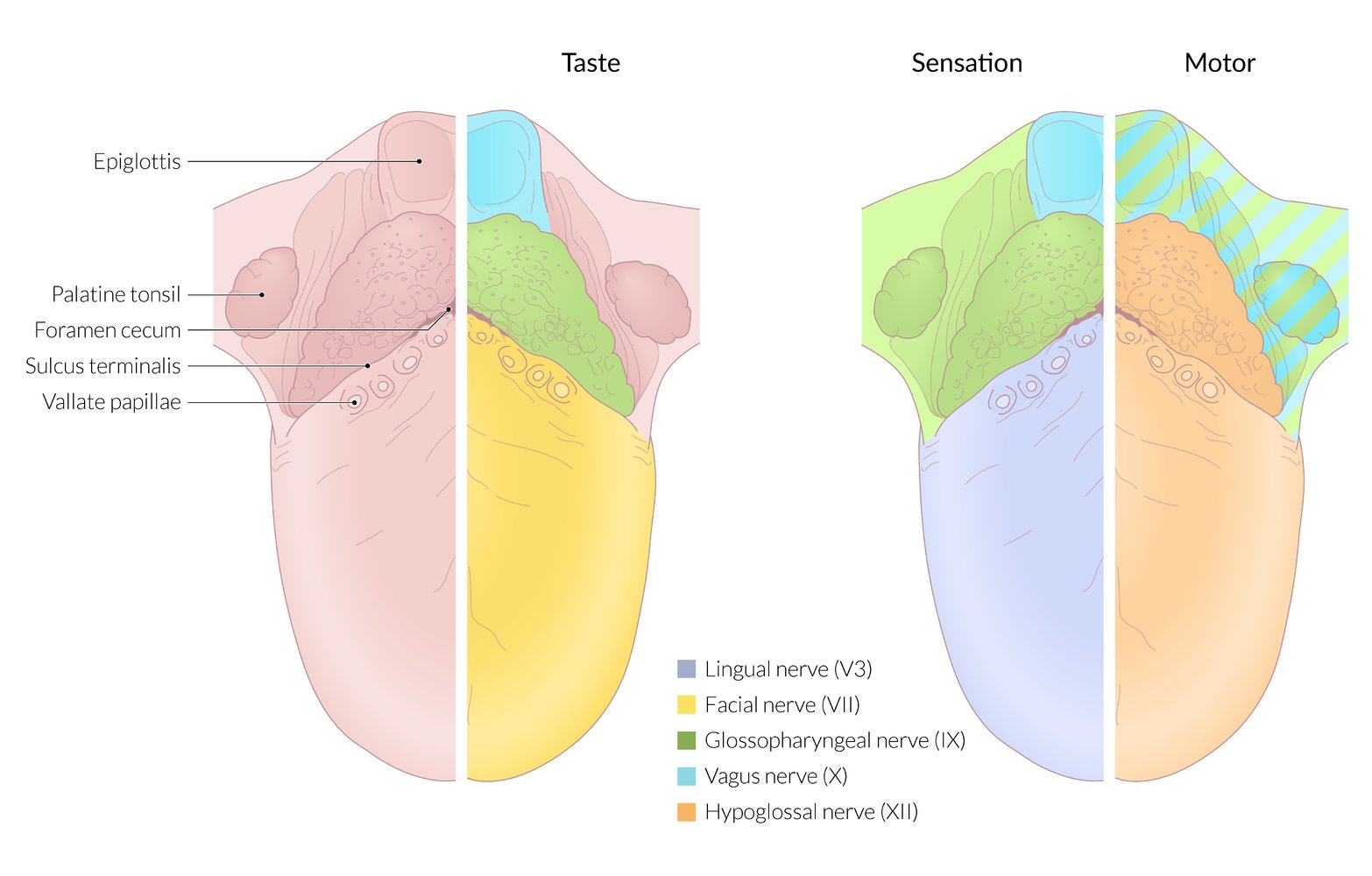

- Altered taste over the posterior aspect of the tongue

- Difficulty swallowing

Lesions that affect the glossopharyngeal nerve typically also affect the vagus nerve because the two nerves exit the jugular foramen in close proximity. [16][49]

Diagnostics [49]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the cranial nerve examination.

- Ipsilateral diminished or absent gag response (afferent limb).

- Loss of taste in the posterior third of the tongue.

- Sensory loss over the soft palate, upper pharynx, and posterior third of the tongue (including loss of taste sensation)

The carotid sinusbaroreceptors are innervated by the carotid sinus nerve, a branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Injury to the glossopharyngeal nerve may result in impairment of the baroreceptor reflex. [50]

Further evaluation

- Consider high-resolution MRI orbit, face, and neck, in conjunction with MRI head (without and with IV contrast) to assess for underlying cause. [17][18][51]

Treatment

- Consults [49]

- Neurology for all patients

- Otolaryngology for patients with laryngeal or pharyngeal symptoms (for laryngoscopy)

- Speech therapy as needed

- Address suspected underlying cause if identified.

- Consider acute pain management with adjuvant analgesics for glossopharyngeal neuralgia. [51]

Etiology

- Trauma (skull base fractures)

- Diabetes

- Inflammation

- Aortic aneurysms

- Neurodegenerative conditions

- Tumors

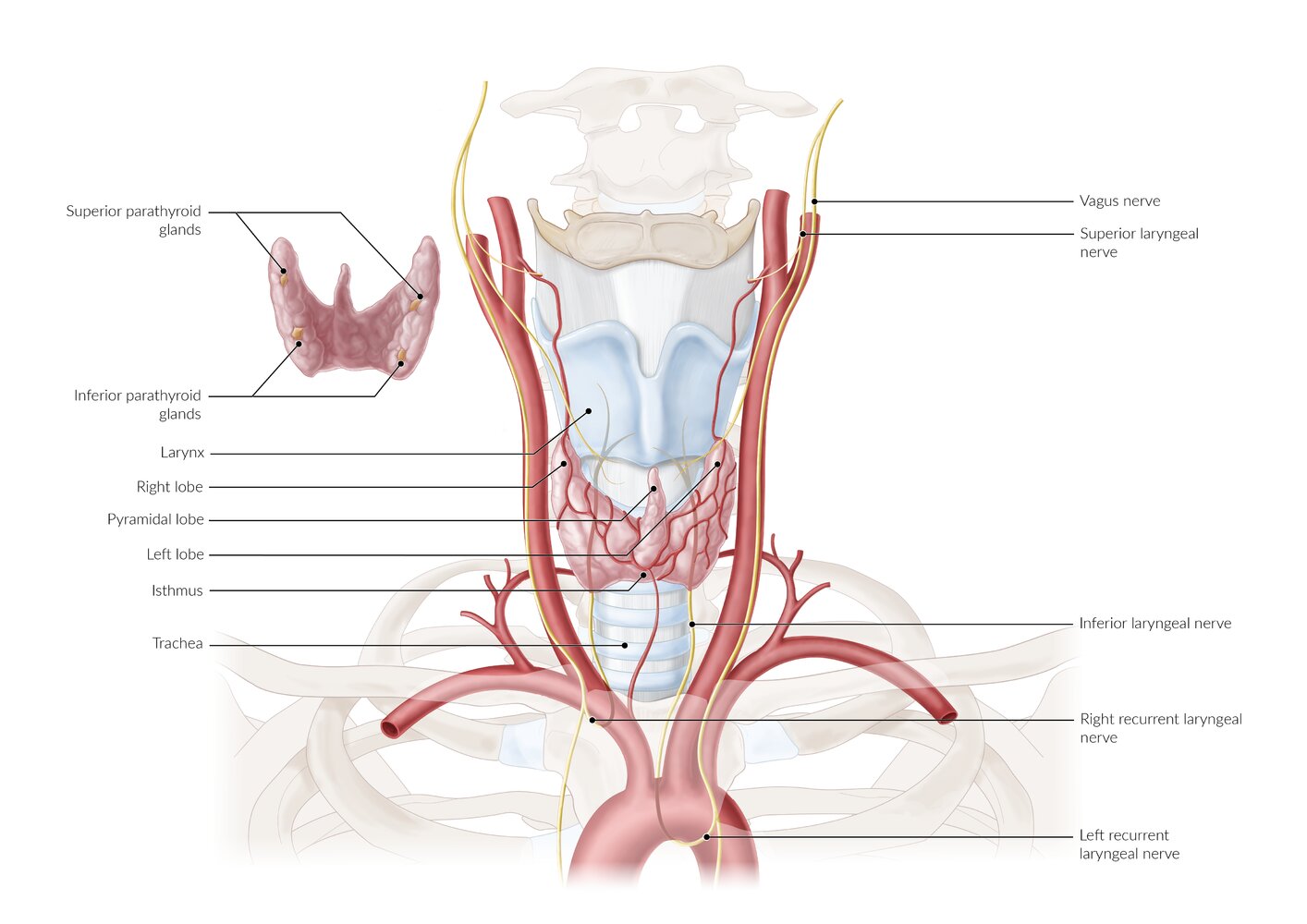

- Surgery (e.g, recurrent nerve injury during thyroidectomy)

Clinical features

- Nasal speech

- Dysphagia, aspiration

-

Vocal cord paralysis, manifesting as:

- Dysphonia (hoarseness) in unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

- Aphonia and inspiratory stridor in bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

- Features of gastroparesis, e.g., postprandialbloating

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis may be asymptomatic due to compensation from the contralateral vocal cord.

Lesions that affect the vagus nerve typically also affect the glossopharyngeal nerve because the two nerves exit the jugular foramen in close proximity. [16][49]

Diagnostics [16][49][52]

Cranial nerve examination

- Perform a focused HEENT examination and cranial nerve examination, assessing for:

- Diminished or absent gag reflex(efferent limb) and/or cough reflex (afferent limb; impulses travel via the internal laryngeal nerve)

- Uvular deviation: Articulating "ahh" will cause the uvula to deviate away from the affected side.

- Flaccid paralysis and ipsilateral lowering of soft palate

- Pharyngeal dysfunction: Ask the patient to swallow some water; choking or difficulty swallowing indicated dysfunction.

- Tachycardia (resting heart rate > 100 beats per minute)

- Observe the patient's breathing and voice, assessing for: [52]

- Stridor: May indicate bilateral vocal cord palsy; perform immediate airway management and consult otolaryngology.

- Dysphonia: Hoarseness is suggestive of unilateral vocal cord palsy; aphonia is suggestive of bilateral vocal cord palsy.

- Dysarthria: Dysphonia with dysarthria and dysphagia may indicate neurological pathology (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

-

Consult otolaryngology for evaluation of larynx and pharynx, including: [49][52]

- Laryngoscopy (direct and indirect): to identify vocal cord palsy (unilateral or bilateral)

- Fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopy: to evaluate the upper respiratory tract for structural abnormalities or foreign bodies

Isolated palsy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve(s) indicates that the site of the lesion is most likely distal to the hyoid bone. More proximal lesions manifest with dysphagia, nasal speech, palatal paralysis, and uvular deviation. [17][49]

Dysphonia in a patient with a neck mass, dyspnea, stridor, progressive neurological symptoms, history of tobacco use, or history of surgery on the head, neck, or chest requires urgent evaluation by an otolaryngology specialist to evaluate for a potentially serious underlying cause. [52]

Further evaluation [16][17][18]

Based on clinical and laryngoscopic findings, consult neurology and consider further evaluation, including:

- MRI head and brainstem (without and with IV contrast): to evaluate for proximal or intracranial etiologies, such as stroke or neoplasms

- CT neck and proximal chest (with IV contrast): to evaluate for distal causes, such as thyroid, neck mass, or thoracic aortic aneurysm

Treatment [49][52]

Treatment varies depending on the cause and severity of symptoms; options include the following:

- Expectant management: Patients with dysphonia of unclear cause may be observed for up to 4 weeks if no indications for expedited laryngoscopy are present.

- Voice therapy: may be performed alone or in conjunction with surgery [53]

-

Surgery [54]

- Unilateral vocal cord palsy: interventions to reduce the glottic opening (e.g., injection laryngoplasty) or thyroplasty

- Bilateral vocal cord palsy: tracheostomy or interventions to enlarge the glottic opening (e.g., lateral fixation of the vocal fold, arytenoidectomy, and/or cordotomy)

Bilateral vocal cord palsy with stridor and dyspnea is a potentially airway-threatening condition. Consult otolaryngology urgently to secure the airway (e.g., via tracheostomy). [54]

Etiology

- Iatrogenic: most commonly from surgery of lateral cervical region; , especially posterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle (e.g., resection of posterior cervical lymph nodes, radical neck dissection)

- Trauma (e.g., sternoclavicular joint dislocation, acromioclavicular joint dislocation)

- Tumor

Clinical features [55]

- Shoulder pain and heaviness

- Difficulty or inability to raise hand overhead

- Neckline asymmetry

Diagnostics [16][17]

Cranial nerve examination

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the cranial nerve examination.

- Inspect upper back, shoulder, and neck

-

Paresis, atrophy, and/or asymmetry of the trapezius muscle

- Ipsilateral shoulder drooping

- Lateral winging of the scapula

- Paresis, atrophy, and/or asymmetry of the sternocleidomastoid

-

Paresis, atrophy, and/or asymmetry of the trapezius muscle

- Assess the trapezius muscle.

- Ask the patient to shrug their shoulders.

- CN XI palsy results in weakness during elevation of the ipsilateral shoulder.

- Assess the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- Ask the patient turn their head from side to side.

- CN XI palsy results in weakness in turning the head towards the contralateral side

Muscular atrophy is a late sequelae of CN XI palsy. [55]

Further evaluation

Consider further evaluation for underlying cause based on clinical findings. Studies may include:

- Imaging (i.e., MRI orbit, face, neck without and with IV contrast or CT neck with IV contrast): to evaluate for possible underlying compressive cause (e.g., malignancy) [17][18]

- Electromyography (EMG): to assess severity of impairment

Accessory nerve palsy should be part of the differential diagnosis of neck and shoulder pain. [55]

Treatment [16]

- Consult neurology and/or head and neck or plastic surgery.

-

Conservative measures can be considered for patients with mild dysfunction and/or evidence of improvement on follow-up. [55]

- Pain control with arm sling

- Physical therapy to strengthen shoulder girdle musculature

- Surgical measures (e.g., nerve grafting, neurolysis) [55][56]

- May be preferred for acute traumatic causes with severe dysfunction

- Consider within 6 months of onset if there is poor response to conservative management

Etiology

- Tumors (e.g., glomus jugulare)

-

Trauma

- Occipital condyle fractures, skull base fractures

- Iatrogenic trauma (e.g., neck dissection, endotracheal intubation, laryngeal mask airway) [57]

- Dissection of the internal carotid artery

- Stroke

- Demyelination

Clinical features

- Dysarthria

- Difficulty swallowing

- Atrophy and fasciculation of the tongue on the side of the lesion

Diagnostics [17]

Cranial nerve examination

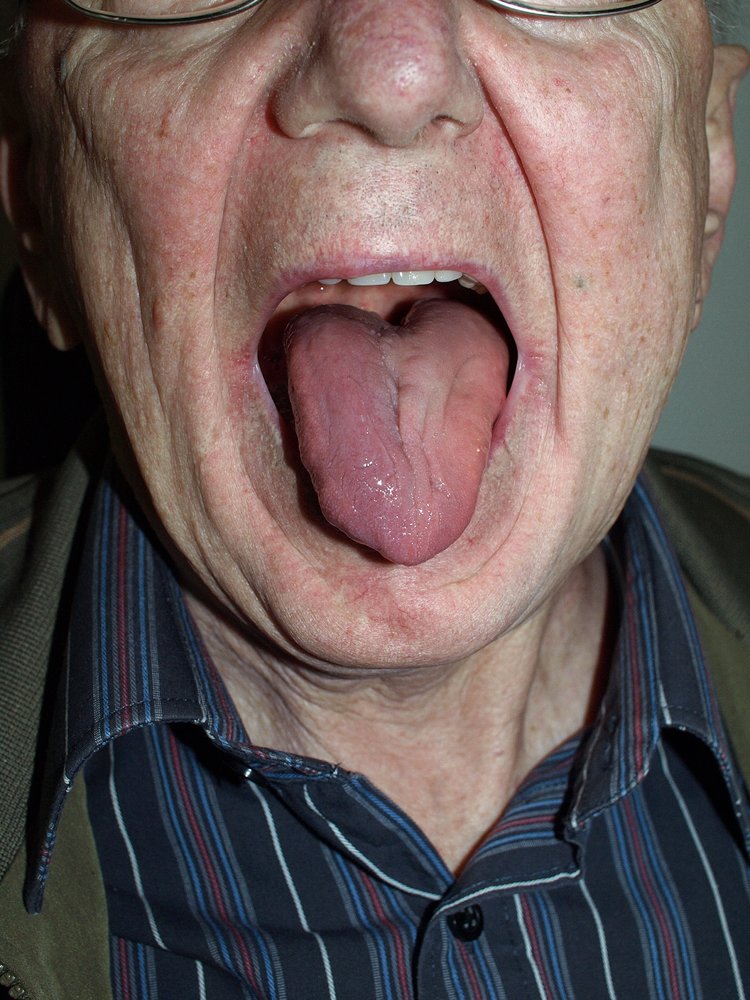

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the cranial nerve examination. Ask the patient to:

- Press tongue against each cheek: Pressure to the cheek of the affected side might be increased.

- Stick out their tongue

- Deviation of the tongue to the ipsilateral side when protruded due to weakness of the ipsilateral tongue muscles.

- Signs of unilateral lower motor neuron damage: tongueatrophy, fasciculations, or asymmetry

Further evaluation

Consider further evaluation to identify lesion location and underlying cause based on clinical findings. Studies may include:

- Imaging [17][18]

- MRI head and neck (without and with IV contrast) : to locate nerve lesion and possible etiologies

- CT skull base and neck with IV contrast: may be performed in conjunction with MRI to evaluate the foramina and skull base (e.g., for fractures, skull base tumors)

- Electromyography (EMG): to assess severity of of nerve damage

Treatment [16]

- Consult neurology and speech language pathology.

- Consider early surgery in acute nerve injury. [16]

- Unilateral nerve injury

- May spontaneously resolve within 6 months.

- Advise patients to chew on the unaffected side.

- Bilateral nerve injury: Consider enteral feeding strategies for swallowing difficulty.

| Overview of multiple cranial neuropathies [58][59][60] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Affected cranial nerve | Cause | Clinical features |

| Chronic meningitis |

|

|

|

| Jugular foramen syndrome |

|

|

|

| Cavernous sinus syndrome |

|

|

|

| Cerebellopontine angle syndrome |

|

|

|

| Guillain-Barré syndrome |

|

|

|

| Multiple sclerosis |

|

|

|