Eosinophilic lung diseases encompass a spectrum of pulmonary conditions characterized by pulmonary and/or peripheral eosinophilia. These disorders may be idiopathic or secondary to etiologies such as helminth infections, pharmacological agents, or environmental triggers. Diagnostic workup generally includes clinical evaluation, imaging studies, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and occasionally lung biopsy to confirm pulmonary eosinophilia and exclude differential diagnoses. Eosinophilic pneumonias are a type of eosinophilic lung disease characterized by significant infiltration of eosinophils in the alveoli and pulmonary interstitium. Simple pulmonary eosinophilia (Loeffler syndrome) is characterized by transient migratory pulmonary consolidations on imaging with peripheral eosinophilia that typically resolves spontaneously within a month. Acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia is a rapidly progressive eosinophilic pulmonary condition that may lead to hypoxemic respiratory failure, often precipitated by recent exposure to inhaled irritants such as tobacco smoke or dust. Acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia manifests with bilateral reticular opacities and pleural effusions and rapidly improves with a short course of high-dose IV glucocorticoids. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is an insidious eosinophilic lung disorder of unknown cause commonly associated with atopic conditions such as asthma or eczema. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by peripheral and predominantly upper lobe consolidations and often requires prolonged glucocorticoid therapy due to a high risk of recurrence.

Idiopathic [1][2][3]

- Acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia

- Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Infectious causes [1][2][3]

-

Parasitic

- Hookworm infection, ascariasis, strongyloidiasis (e.g., manifesting as Loeffler syndrome)

- Schistosomiasis (manifesting as Katayama fever)

- Other, e.g., paragonimiasis, toxocariasis, trichinellosis, echinococcosis

-

Fungal

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis

- Pulmonary mucormycosis

- Pneumocystis pneumonia

-

Bacterial

- Tuberculosis

- Brucellosis

-

Viral

- COVID-19

- HIV infection

Allergic causes [1][2][3]

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)

- Asthma

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Eosinophilic bronchitis

- Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia

Drug-induced causes [1][2][3]

Medications can cause eosinophilic lung disease through multiple pathways, e.g., hypersensitivity (DRESS), or direct drug toxicity.

- Antiepileptic drugs (e.g., phenytoin)

-

Antibiotics

- Sulfonamides (e.g., sulfamethoxazole)

- Vancomycin

- Minocycline

- Bleomycin

- Tetracycline

- Nitrofurantoin (e.g., manifesting as acute nitrofurantoin-induced lung disease)

- NSAIDs (e.g., aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease)

- Allopurinol

Other causes

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)

- Sarcoidosis

- Malignancy, e.g., non-small cell lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma

- Environmental exposures

- Radiation: See “Radiation-induced lung injury.”

- Inhalation

- Heavy inhalation of dust or smoke

- Tobacco smoke, vaping-associated pulmonary injury

- Recreational drugs, e.g., heroin, crack cocaine, marijuana

See also “Eosinophilia” for guidance on the evaluation of peripheral eosinophilia.

General principles [1][2]

- Consider eosinophilic lung disease in patients with:

- Nonspecific respiratory symptoms and/or chest imaging findings

- ↑ Eosinophils on CBC, BAL, and/or lung or pleural tissue

- Consult specialists (e.g., pulmonology, rheumatology) early.

- Perform a thorough clinical evaluation and obtain diagnostic studies to identify the underlying cause.

- Consider transient causes (e.g., Loeffler syndrome) and idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonias.

- Management is tailored to the underlying disease and end-organ manifestations.

Clinical evaluation [4][5]

-

Focused history

- Duration and severity of symptoms

- Detailed atopy history [2]

- Exposures

- Smoking history

- Use of prescription and/or recreational drugs

- Detailed travel history

- Features of extrapulmonary involvement

- Constitutional symptoms, e.g., fever, night sweats, weight loss, pruritus

- Dermatological features, e.g., rashes

- Gastrointestinal features, e.g., abdominal pain, diarrhea

- Autoimmune or inflammatory symptoms, e.g., joint pain, fever

-

Physical examination

- Vital signs, including pulse oximetry

- Head and neck examination

- Pulmonary examination

- Skin examination

Initial diagnostic studies [1][5][6]

-

Laboratory studies

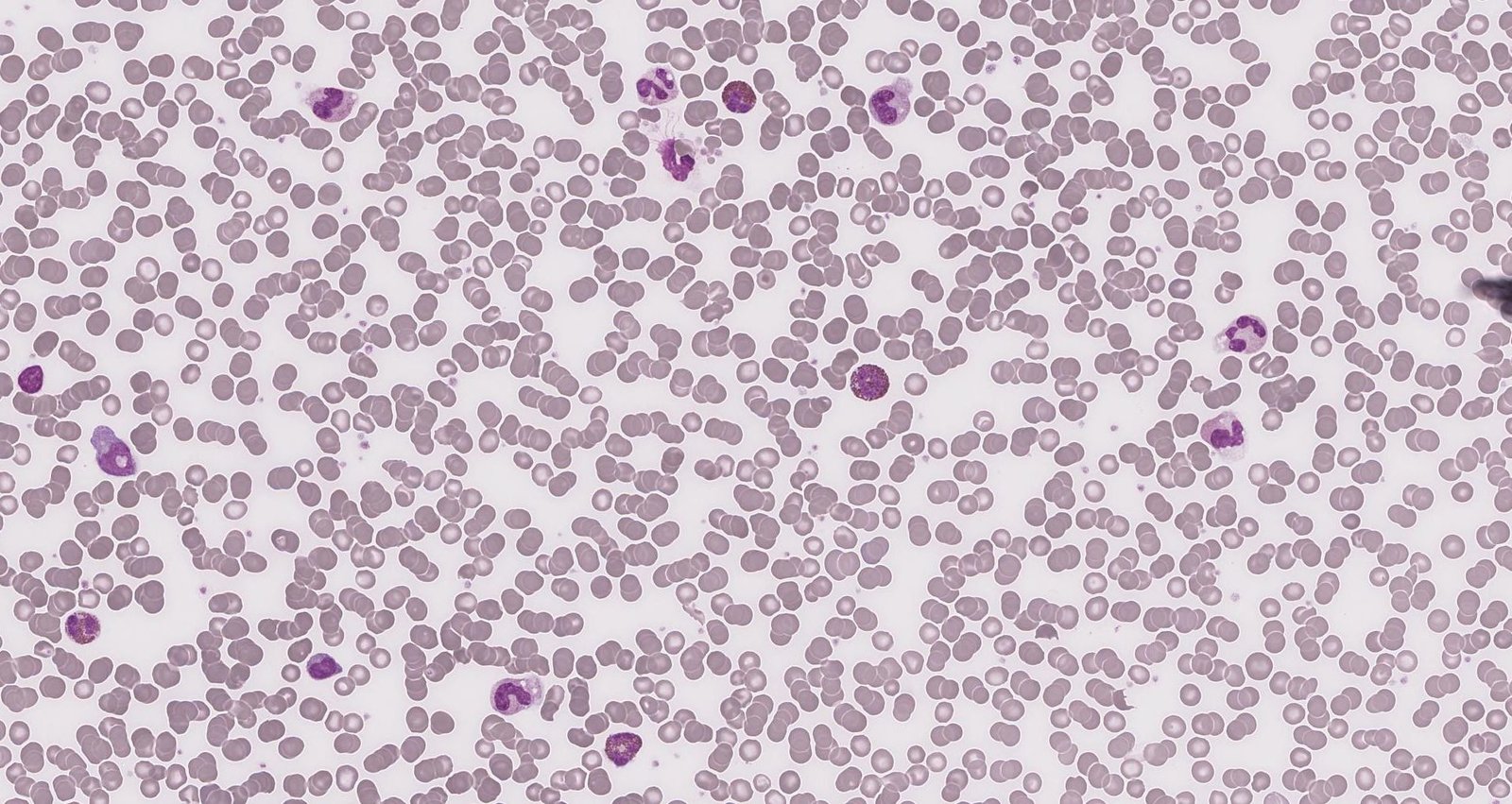

- CBC with differential and peripheral blood smear: confirm eosinophilia

-

Immunoglobulins

- Total IgE levels

- Aspergillus-specific IgE and IgG; see also “ABPA.”

- Autoantibodies: e.g., ANCA; see also “EGPA.”

- Pulmonary function tests (PFTs): Findings differ depending on the underlying cause; see also “PFT findings in obstructive vs. restrictive lung diseases.”

- Imaging studies: e.g., HRCT of the chest and sinuses; see also “Diagnostics for ILD.”

Additional diagnostic studies [5][6]

Further evaluation is based on the clinical presentation and may include the following:

-

BAL fluid analysis

- Differential and absolute WBC counts; eosinophils usually > 10%

- Fungal, bacterial, and mycobacterial cultures

- Testing for parasite ova and parasites

-

Lung and pleura biopsy (surgical or transbronchial approach)

- Evidence of tissue eosinophilia

- Additional findings depending on the underlying cause

-

Additional infectious disease workup, e.g.:

- Cultures and testing for parasite ova and parasites in other fluids or tissues (e.g., sputum sample, stool microscopy, biopsy samples)

- Serologic tests: e.g., for Strongyloides stercoralis, Schistosoma, filariasis

- HIV testing

Overview [2][7]

| Comparison of eosinophilic pneumonias [2][7] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple pulmonary eosinophilia (Loeffler syndrome) | Idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonias | |||

| Acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia | Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia | |||

| Disease trajectory |

|

|

|

|

| Etiology |

|

|

|

|

| Diagnostic findings | Peripheral eosinophilia |

|

|

|

| BAL eosinophilia |

|

|

|

|

| Chest imaging |

|

|

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

|

|

Hypoxemic respiratory failure is common in acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia but rare in simple pulmonary eosinophilia and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.

Definition [2]

Simple pulmonary eosinophilia is a form of eosinophilic pneumonia characterized by transient and migratory eosinophilic pulmonary consolidations and peripheral eosinophilia.

Etiology [2][3]

- Idiopathic (approx. 30% of individuals with Loeffler syndrome) [3]

- Passage of parasites through the lungs, e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworms, or Strongyloides stercoralis

-

Hypersensitivity reactions, e.g.:

- ABPA

- Allergic reaction to certain drugs

Clinical features [2]

- May be asymptomatic

- Mild respiratory symptoms (most often dry cough)

- Fever, malaise

Diagnostics [2]

-

Laboratory studies

- CBC: eosinophilia

- Studies to assess for underlying causes (recommended for all patients), e.g.:

- Testing for helminth infections and other parasites

- Testing for ABPA (e.g., ↑ Aspergillus fumigatus IgE)

- Chest imaging (e.g., chest x-ray, HRCT): one or more transient migratory opacities (typically resolve within 1 month)

Consider differential diagnoses for migratory pulmonary opacities, e.g., recurrent aspiration, pulmonary vasculitis, pulmonary hemorrhage, and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. [2]

Management [8]

- Management of the underlying cause

- Glucocorticoids (e.g., methylprednisolone) if symptoms do not improve within a month [8]

Loeffler syndrome typically resolves spontaneously within a month. [2]

Definition [1]

Acute idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia is a form of eosinophilic pneumonia characterized by the sudden onset and rapid progression of an acute febrile illness, typically in previously healthy individuals.

Epidemiology [8]

- Rare; exact prevalence unknown

- ♂ > ♀

- Peak age 20–40 years

Etiology [8]

- Idiopathic [8]

- Typically triggered by respiratory exposures, e.g.:

- Tobacco smoke (including secondhand smoke) [8]

- Vaping

- Dust inhalation

Clinical features [3][7]

- Acute onset (< 1 month)

- Dyspnea and cough

- Fever, myalgias

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Oxygen saturation < 90% on ambient air

Patients may present with severe ARDS requiring mechanical ventilation. [7]

Diagnostics [7][8]

Diagnostic criteria [7]

- Acute onset of febrile respiratory syndrome

- Characteristic chest imaging

- Hypoxemia

- Lung eosinophilia

- Other causes of acute eosinophilic lung disease have been ruled out

Diagnostic studies [8]

-

Laboratory studies

- CBC: Eosinophil count is typically initially normal and increases to high levels within days.

- ABG: PaO2 < 60% and/or PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300 mm Hg

- BAL: eosinophilia ≥ 25%

- Imaging (e.g., chest x-ray, HRCT): Characteristic findings include bilateral patchy infiltrates and pleural effusion. [2][8]

- PFTs: may reveal restrictive lung disease with ↓ DLCO

Management [7][8]

- Respiratory support: See “Indications for invasive mechanical ventilation” and “ARDS.”

- High-dose IV glucocorticoids, e.g., methylprednisolone (off-label)

Clinical recovery typically occurs within 24–48 hours of initiation of glucocorticoid therapy. Relapse after discontinuation of therapy is uncommon. [7]

Definition [1]

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is a form of idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia characterized by subacute respiratory symptoms.

Epidemiology [7][8]

- Rare; exact prevalence unknown

- ♀ > ♂

- Peak age: 30–45 years

Etiology [7]

- Idiopathic

- Risk factors include history of asthma or atopy.

Most individuals with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia are nonsmokers.

Clinical features [7]

- Onset: weeks to months

- Dyspnea (usually moderate) and cough (most common features)

- Fatigue, malaise, low-grade fever

- Rhinitis or sinusitis

- Hemoptysis, chest pain, and severe respiratory failure are rare.

Diagnosis [2][7][8]

Diagnostic criteria [7]

- > 2–4 weeks of respiratory symptoms

- Characteristic chest imaging findings

- BAL eosinophils ≥ 40% or peripheral blood eosinophils ≥ 1000/mm3

- Other causes of chronic eosinophilic lung disease have been ruled out

Diagnostic studies

-

Laboratory studies

- CBC: eosinophilia present in most patients (may be severe, e.g., 5000/mm3 and 20–30% of WBC) [7]

- Inflammatory markers: CRP and ESR are typically elevated.

- IgE levels: elevated in the majority of patients

- BAL: eosinophilia ≥ 25% (frequently ≥ 40%) [7][8]

- Imaging (e.g., chest x-ray, HRCT): peripheral and homogenous consolidations, typically in the upper lobes (visible in < 50% of patients) [2]

-

Lung biopsy

- Rarely needed for diagnosis

- Supportive findings include:

- Eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration of alveoli and interstitium

- Interstitial fibrosis

- PFTs: may reveal obstructive or restrictive pulmonary disease and ↓ DLCO

Management [8]

- Respiratory support as needed

-

Glucocorticoids, e.g., prednisone (off-label)

- High doses for 4–6 weeks

- Usually followed by a taper of 3–6 months

- Steroid-sparing biologic therapy (e.g., omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab) may be considered for relapsing or refractory cases.

- Relapse requiring retreatment with high-dose glucocorticoids is common.

Clinical improvement typically occurs within 2 days of initiation of glucocorticoid therapy. [7]